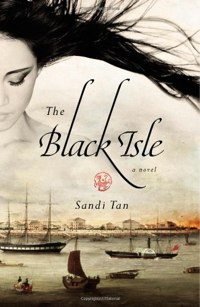

The Black Isle

by Sandi Tan

Born to affluence in 1920’s Shanghai, Cassandra faces formidable afflictions. Her twin brother gets all the attention, and all the best presents. Her mother is distant, her father feckless, and even a child can see that Shanghai is falling apart.

More strangely, Cassandra sees ghosts; indeed, she sees them everywhere, and her growing world is always filled with the hungry spirits of the past. This strange ability shapes Cassandra but does not dominate her; she is not a slayer or a priestess, she’s just a well-drawn Chinese girl who happens to see ghosts.

She lives in interesting times. Her father flees the Depression and heads to the Black Isle, a large island at the tip of the Malay peninsula that shares much with the Singapore we know. Her mother and twin sisters will follow in time; she never sees them again – at least not as you and I see. But even in this new island home, ghosts are everywhere. War follows, and then years as a freedom fighter, and then more years as the neglected former consort of the newly-independent island’s Prime Minister. And then, a distant Professor starts stirring the ghosts once more.

One obvious touchstone for The Black Isle is James Clavell’s King Rat, his good book. The war is the heart of The Black Isle, and Tan quietly builds an argument that for much of China, the short twentieth century was experienced as one long war. Another, less obvious, is the title story of What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank, for Cassandra’s struggle is not so much with her suffocatingly-close twin and her war-criminal lover as with herself. Self-loathing would be conventional, and Cassandra is bored by convention, yet she cannot escape the haunting wrongness. Cassandra sees ghosts – aggrieved spirits – everywhere, and in her world betrayal is the norm, peace the silent and easily-forgotten exception.

The Black Isle is a Secret History of a country that resembles one we know, blending myth, history, and invented detail. This was an intriguing decision, inviting the reader to imagine the ghost books that must have been imagined in its making. On the one hand, little would need to change to make this a literal secret history, though doing so might incur the displeasure of that nation’s leaders. Alternatively, we could follow China Miéville into urban fantasy, forbearing the fields we know entirely and describing an imaginary world that just happens to be China much as City and The City describes an imaginary Eastern Europe and Foundation describes the fall of an imaginary Rome.

All historical fiction invites suspicion of Orientalism. Tan handles her sexy Chinese protagonist with grace and honesty. Knotty and perhaps unsolvable questions of craft and history appear continuously here, as perhaps they must, but Tan (like Cassandra) manages to avoid disaster while not fearing to get down in the muck with the ghosts

Cassandra embodies a complex and thoughtful reflection on femininity and feminism in the Chinese diaspora.