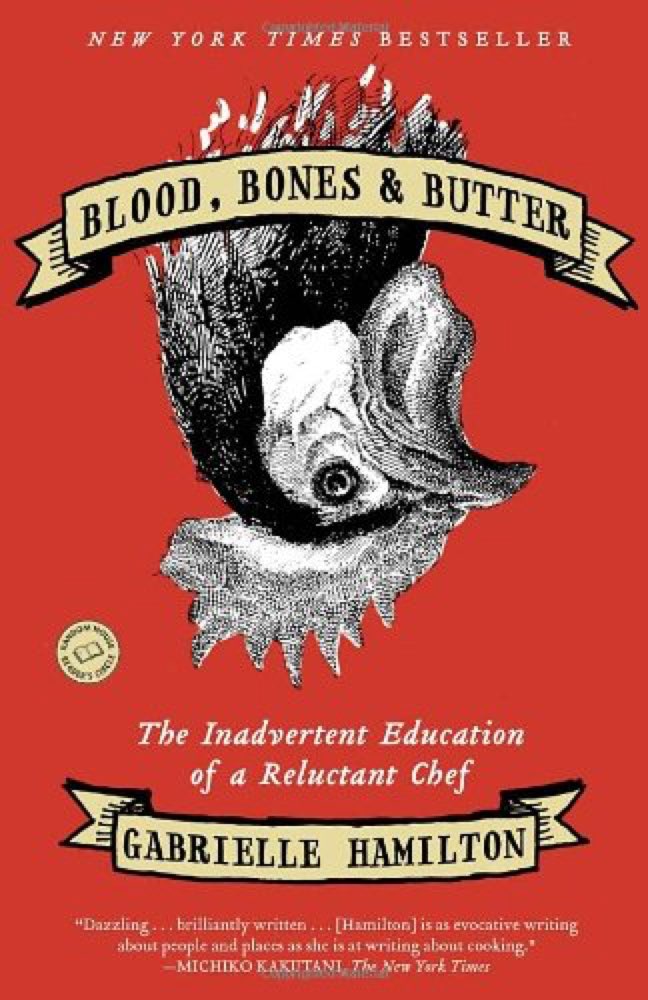

Blood, Bones, and Butter: The Education of a Reluctant Chef

by Gabrielle Hamilton

A literary memory the author (and chef) of Prune. This successful and accomplished literary memoir redeems the author’s early MFA: she can write as well as cook. The subject, of course, is the writer. That’s the subject of Prune, too, though it might be harder for people who don’t cook to see the extremely clever and skillful blending of commentary, anecdote, and advice in the latter. This book, with accounts of youth hostels in Europe and early struggles with the restaurant, is more familiar in construction but also replete with subtly skillful touches.

In the food, Hamilton is arguing against Keller and Adriá and Redzepi and making a case for simple and comfortable food. She affects to dislike overtly complex texts and overtly complex food. Yet she is not beyond being clever herself: in Prune, she keeps the Brandy Stinger (brandy and green creme de menthe, once inexplicably favored by USAF fighter pilots) on the menu but tells her staff that she wants to meet anyone who actually orders one. And here, while affecting to simply record here progress toward owning a successful restaurant, she carries on an interesting dialogue first with Anthony Bourdain (whose brilliant Kitchen Confidential celebrated and popularized a viciously macho portrait of the professional kitchen) and then with MFK Fisher. Fisher famously wrote of love and food, but her loves were seen in the shadows and the food was always foremost; in the second half of Blood, Bones, and Butter, her failing marriage (a marriage she always expected to fail, since she entered into the marriage simply to help a friend get a green card) takes the focus to the virtual exclusion of food. In the end, we see the chef only on vacation in Italy, where she is not permitted to cook, and much of what food discussion remains is only about what we cannot eat (burratta at home, because it’s never good; anything but eggplant at the summer house, because that’s all they grow there).

It’s striking that while the author is gay, and is not particularly shy about alluding to her relationships, this memoir almost never focuses on her orientation.It’s nice that we can have a candid autobiography of a woman who simply happens to be gay, a woman for whom this is part of her life, in the way her parents’ divorce is, but it’s not a central concern.