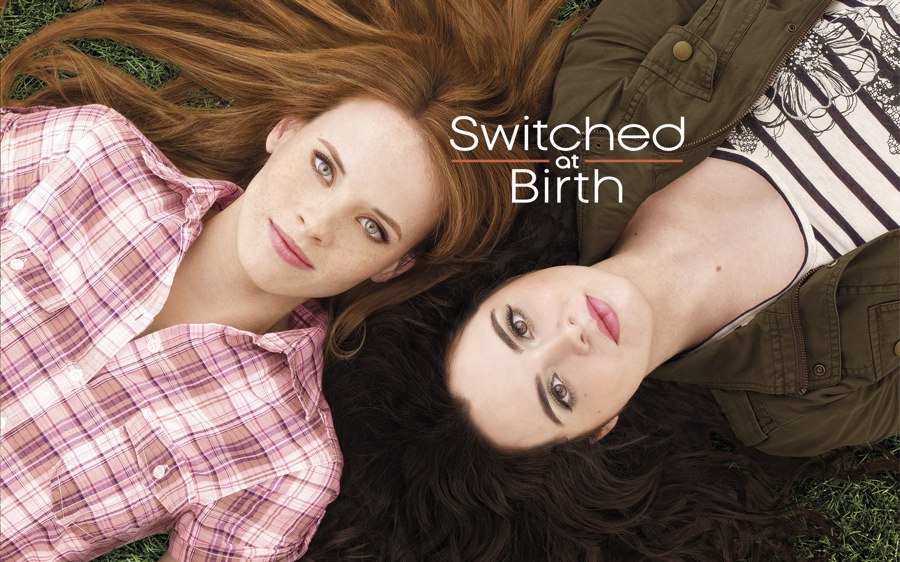

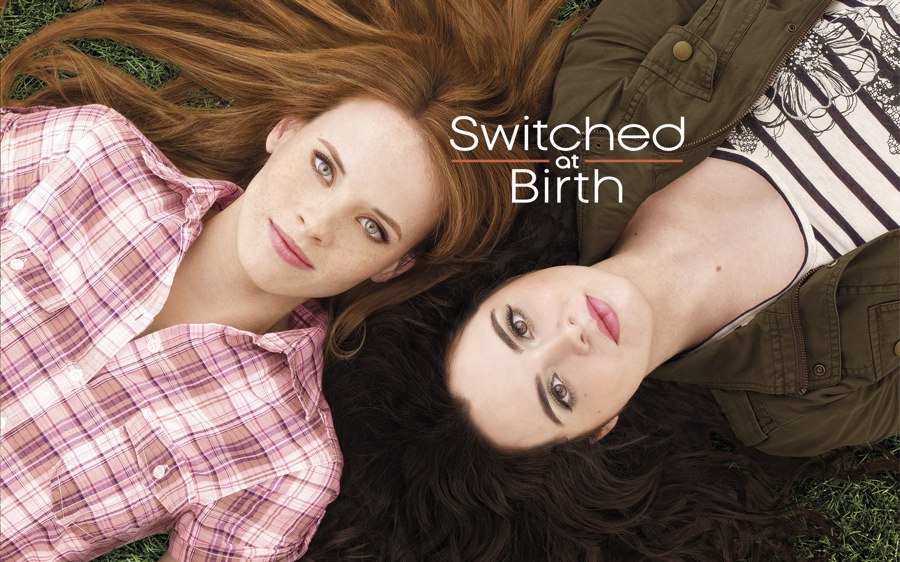

I took a look at the first season of Switched At Birth after reading Emily Nussbaum’s enthusiastic review in The New Yorker. The first season, at least, is remarkably good.

The raw material is not promising. Two infant girls were accidentally interchanged in a hospital, sixteen years ago. Since this is TV, one grew up rich, the other poor. One is blonde and bouncy, the other dark and brooding. Both are beautiful and brilliant and beloved. And one is deaf.

What makes this work is a great combination of metaphor and problem play. The problem of building a relationship with someone with someone you don’t quite understand is always with us. In the show, we have “mixed†couples where one hears and the other doesn’t, and of course these stand for the questions of all mixed couples: black and white, gentile and Jew. We recapitulate Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. DuBois in Daphne, the deaf daughter who is willing to speak, and her friend Emmett, who won’t: hearing people will meet him on his terms or not at all.

One year, my high school did Carousel with a black Billy Bigelow, and that seemed perfectly sensible to us — especially since Evan Moore could sing the part like nobody’s business — but now I realize that probably raised some eyebrows. Of course, you’re suppose to read Bigelow as a metaphor for black America, but the whole Old New England setting (is this supposed to be Cape Cod?) is supposed to cover that up a bit. And of course, as it often is on Broadway, it’s a question of whether a nice Jewish girl can date a boy whose parents aren’t part of Our Crowd.

As kids, we were very sophisticated and mature about adoption. Everyone knew it didn’t matter. But it turned out to matter a lot to a bunch of people I’ve known as grownups (including some of those sophisticated kids). Then again, we meet people every day whose face says Seoul and whose business card says “Regina Gottlieb.â€

Emmett, the deaf separatist, drives some fascinating stage business since his performance has to be accomplished without speaking. Daphne, on the other hand, speaks badly — and that makes for challenging dialect work and different acting challenges: like Cassie in A Chorus Line, this actress has to take a lifetime of training to use her voice and, well, not do it. Almost everyone is learning to sign, and I suspect we’re expected to be learning, too.

It’s fluffy, in short, but there are good bones here. Streaming at Netflix and worth the time.