The Science Fiction Encyclopedia is becoming ridiculously good.

Here’s an article on Hungary. Did you know that 19th century Hungarian utopian fiction is that origina of SF? Neither did I. Awesome scholarship, without grants, without tenure.

The Science Fiction Encyclopedia is becoming ridiculously good.

Here’s an article on Hungary. Did you know that 19th century Hungarian utopian fiction is that origina of SF? Neither did I. Awesome scholarship, without grants, without tenure.

Bruce Bartlett: Revenge of the Reality Based Community. Highly recommended.

I’ve paid a heavy price, both personal and financial, for my evolution from comfortably within the Republican Party and conservative movement to a less than comfortable position somewhere on the center-left. Honest to God, I am not a liberal or a Democrat. But these days, they are the only people who will listen to me. When Republicans and conservatives once again start asking my opinion, I will know they are on the road to recovery.

Me at Blue Mass Group.

We’ve all read about the importance of databases and cell phones, email and text messaging to the Obama and Warren campaigns of 2012. The success of VAN and Narwhal and campaign media outreach were vital. But the next election will come; we should think now about the technology landscape we’ll face then.

The middle volume in White’s compendium of exhaustive studies of every facet of London in the 20th, 19th, and 18th centuries. Fascinatingly, White began with the 20th-century volume. I discovered the series because TLS lauded the newly-arrived book on the 18th century.

Each chapter follows a street that provides a focus for its topic: Spring Gardens for government, Broad Sanctuary for school administration, Flower and Dean Street for common lodging houses and the very poorest laborers. If you want to know how the administrative structure of the Metropolitan Sanitary Commission affected the growth of London and the health of its residents, this is the book for you. White delves into fascinating detail about how things actually worked, from land speculation in Belgravia to prostitution in the back of the music hall. This is not an anecdotal account, and White generally focuses on streets and highways; we learn about offices and institutions, clerks and magnates, but hear less of what went on inside those offices or where people ate lunch. At 624 pages, there’s not much space to lament what was left out, and even the administrative histories of the London School Board and the New Police provide a certain narrative satisfaction.

I’ve been spending a lot of time lately on planes and in sickrooms, worrying about everything that can be worried about, and also about some things that they tell me cannot be worried about.

I am determined to prove them all wrong.

But, while doing all that, I worried a little bit about the ragged logic in the Tinderbox 6 map’s click handler. This works fine right now, but the code has a few too many conditionals:

if (part==kMapInBody) { ..... }

if (part==kMapInPrototypeTab) {...}

if (part==kMapInBadge) {...}

So, now that we’ve got the apparent hard disk failures licked and we’ve got the new Tinderbook Sandy set up, let’s tear down maps again and rebuild them a little better.

Delightful birthday dinner in Chicago at Sable. Heather Terhune’s gastro-bar has serious and ambitious food, of which the eGullet crowd is notably fond. The truffled deviled eggs lived up to their billing, and the veal meatballs had a nifty walnut cream sauce. The sweet corn brulée has been controversial, but I’m a fan; I might even buy a propane torch to give this a try. The big win was a quietly complex dish of duck sausage (pistachio and juniper), served with duck crackling and foie gras butter: this is using the whole bird with a vengeance, but where Journeyman might give you a beautiful plate with six or ten separate (but related) products, this is one simple dish that uses all these complicated products together to get lots of textural interest and interesting flavor differences into a simple bowl of sausage.

When did it become impossible to make dinner reservations in the provinces, even ten days in advance? I struck out at Topolo, The Girl and The Goat, and Schwa, though Schwa tried really hard, and Sable couldn’t do better than 9:30. Worth the wait. Given the hour, I limited myself to one cocktail (a Journalist).

In this daring and dazzling overview of the field and its history, Stephen Lekson interweaves the history of the Southwest and the history of Southwestern archaeology. This dual narrative turns out not to be an affectation, for our ideas of how Anasazi and Hohokam people lived were deeply shaped by personalities and institutional histories. In particular, the presence of a border between Mexico and North America has separated Chihuahua from Arizona and New Mexico in a way that would have been invisible and absurd to the fourteenth century.

Lekson builds his conjectural history from a number of fundamental assertions, some of which differ dramatically from American archaeological convention. He asserts that “distance could be managed” – that people knew a lot about what was happening hundreds or thousands of miles away. Their knowledge wasn’t exact and it wasn’t current, but because people doubtless heard stories and repeated them, Lekson assumes that the Anasazi knew something about Mesoamerica far to the South, and also something about Cahokia far to the East. When “the Turk” led Coronado and company from Pecos out into the great plains, Lekson thinks, he knew exactly where he was going and what they would find on the banks of the Mississippi – he just hadn’t received the memo that the great Mississipian city had collapsed a few centuries ago.

Similarly, Lekson is very reluctant to accept temporal coincidences. If two events happen in sequence, he is happier to assume a causal sequence or a common antecedent than to posit mere coincidence.

The historical (rather than methodological) idea that really matters here is a fresh interpretation of Pueblo IV as a deliberate ideological rejection of the Chaco phenomenon. The Pueblos were not always peaceful and egalitarian; as Lekkson wrote in The Chaco Meridian,

Does all this sound anthropologically familiar? If I were describing a neolithic center in Turkistan or Shansi or Wessex or Bolivia or Illinois, what would we think? Chaco was socially and politically ‘complex’ — that is, a hierarchy with definite haves and have-nots. Hierarchy, not heterarchy: A few people at Chaco regularly and customarily directed the actions of many other people, and those few lived in more expensive houses and had more baubles (at least in death) than the many. Were they chiefs, priests, kings, queens, duly-elected representatives? Who knows? And, for now, who cares? They were elite leaders, Major Dudes: that much seems clear. If ever anyone in the Pueblo Southwest were elite, it was those two guys buried in the famous log crypts of Old Bonito. Those boys had power.

Lekson rejects the language of critical theory as emphatically as the heirs of Mimbres rejected its traditional iconography. That’s interesting, and he has developed a supple and flexible informality that combines precision and concision with a disarming accessibility. This is in many ways a brave book, one whose conclusions will not always suit its readers’ politics. Lekson’s history may not be the past that contemporary Southwesterners would like to imagine, but this fascinating and beautifully-argued reexamination of the evidence restores to the Southwestern past the possibility that history happened there.

This fresh collection of Hornby’s superb book columns from The Believer is just as much fun as its predecessors (here, here, and here). Each month’s entry begins with a list of Books Bought and a separate list of Books Read. Both are very much worth reading, even though they seldom overlap much. This time, there’s a lot of Muriel Spark, with whom I’m going to have to get better acquainted.

Christina Rosetti, writing about her brother’s wife:

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel -- every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

I’m delighting in Stephen Lekson’s A History of the Ancient Southwest. Lekson is the great prose stylist of history today, and one of the most capable writers of footnotes of all time.

One dispute that has rent Southwestern archaeology for generations has been what ancient peoples knew about things hundreds or thousands of miles away. The most distant Chaco outliers are 450km from the center; could that really be a regional system? From Chaco to Paquime is about 700 km; from Mimbres, Paquime was about 450km. From Chaco to Cahokia was something like 1800 km; could there even have been rumors? But Lekson takes as his premise that everyone knew everything; ancient people were smart, they got around, and they were curious about the next valley and the evening news.

Incidentally, the distance from the pyramids to Jerusalem or Jericho is about 450km – the radius of the Chaco horizon. And we’re reasonably confident that, a long time ago, some Egyptian workers underwent an ideological change and went out for a long walk. It took a generation to get where they were going. Not everyone went, and not all the people who would make up their new kingdom traveled along; the travelers were elites. The migrants are not immediately obvious in the archaeological record; there are Canaanite towns with pigs and other towns without. Not the same, of course; those guys had (a few) wheels, and knew about domesticated cattle, and they had writing. But Lekson has a point: distance can be managed.

So, for a while there during the campaign it seemed very iffy. But in the end, discipline and being on the right side of the issues prevailed. Yes, Elizabeth Warren won!

Oh, and that guy Obama too.

That was Paul Krugman at 2AM on the morning after the election, and he was right. She’ll be a fine senator. The campaign was a tremendous effort, and I was shaking in my boots right to the end. But back in July I wrapped up a house party that was descending into maudlin strategic wrangling with an impromptu claim that it looked really close at the moment but by election day we’d be ten points ahead. It was eight. In Malden, we went from an 1800 vote margin in the special election to a 6200 vote margin in this one.

But, man, was it hard to help these people.

Back in February, I started sending out offers of assistance. Need a web site? Need collaborative writing tools? Need something written? Need lunch? I was your guy. And I got a few friendly emails, but nobody gave me work.

I think that Tinderbox would be a terrific tool for field organizers. I offered copies — as many as you need. Training? You got it. Want it non-disclosed to be sure I’m not a snake-oil charlatan? Fine.

Not a nibble.

Starting in June, we had “leadership” meetings in a pizzeria to plan the campaign for our 50,000-person city. I was asked to design a four-sentence handout for the city’s July 4 celebration. We went through something like four drafts. At the last minute, one volunteer decided to replace all the copy with pabulum and threatened to quit and start a rival organization. Great.

I begged the campaign’s new media director for work of any sort. Crickets. In July, I launched a miniature campaign inside the campaign, calling in favors from colleagues and politically-connected former employees, just to get the new media director to respond to my email. She was encouraging in lots of directions, and never wrote back.

The logo you see above? I photoshopped it. I asked everyone, all the time, for the campaign graphic standards. What’s the font? What are the PMS colors? No one knew, or knew anyone who knew. That’s 100,000 impressions right there, and mine is a very niche blog. I tried to convince someone to do blogger outreach. I tried to convince someone to let me do blogger outreach, inside or outside the campaign. No answer.

I begged the North Shore Field Director for work. “Knock on doors, make phone calls.” But I’m lousy at canvassing, and I have a terrible time hearing the phone, and I’m rather good at a bunch of other things. I begged the 20-something who was running Volunteers for the summer.

“I’m too busy,” she told me.

“I can manage, I can organize, I can screen your emails.” I told her. “I can write training documents so you don’t have to spend 40 minutes with every new volunteer. Let me help you.” She told me to make phone calls.

This was a recurrent theme. Linda came in for phone bank training, went home, and wrote a manual for new phone bank people. I don’t think anyone got around to using it. Lots of people have special skills or talents – lawyers can litigate and negotiate, writers can write, programmers can code, chefs can cook, and people who happen to have a van or a pickup can haul stuff. We never found out who could help and how; the field organizers were being evaluated on doors knocked and phone calls made, and pumping those numbers for this week was what mattered.

In July, I asked that leadership meeting, “How many volunteers will we need on November 6?” We didn’t have an answer then, nobody seems to have thought about it until October, and then we found ourselves scrambling to get bodies to cover the bare necessities at the polls.

This was an extraordinarily well funded campaign, but until the end we never had sufficient collateral. We hoarded bumper stickers. Getting a lawn sign was a mark of great favor with headquarters. We printed our own brochures on our own ink jet printers.

And, in all this time, I never saw Elizabeth, never heard her stump speech. I never saw Mindy Myers, the campaign manager. I tried to get information on speeches for the Malden For Warren web site, and was told by the Volunteer Coordinator that they were secret, lest Republicans show up.

Some of this is a matter of local politics: the Malden Democrats still inhabit a world where the big social issue is getting the Irish and Italian immigrants into the mainstream of society. The big events have dinner at 5:30 and lots of walkers and guys singing Irish songs. The city has changed; we still have lots of new immigrants, but they’re from China and South Asia and Eastern Europe and Haiti, and we have lots of young folks too, but working the St. Patrick’s Day crowd is the way it’s always been done. (Someday soon, someone will push gently on the Malden Democratic City Committee and it will simply fall over.)

Some of the problem was management by metric. It was clear that the field organizers knew that they were always being evaluated, and so we were always knocking doors and placing phone calls. The main Web site collected volunteer emails for months, but nobody seems to have done anything with those names, or knew who might know about them, and nobody cared because getting more volunteers for the campaign wouldn’t improve their numbers for the week.

And some of it was just timidity. Whatever you can say about Elizabeth Warren, she’s not a timid woman, but her messaging was often very timid indeed. The constantly iterated claim that “She’ll work for you” was just about indistinguishable from her opponent’s slogan, “He’s for us.” The early campaign focused on “She’ll fix what’s broken in Washington,” which (a) is false in the event, as there’s nothing she can do about the tea party in the House, and (b) is in any case a Republican talking point. In a working class city in the grip of a nasty recession, we were instructed to pitch people on Warren as a “fighter for the middle class,” not reflecting on whether our audience saw themselves as part of the middle class.

It was a ton of work. It was painful. If I were starting over, I think I’d work entirely outside the campaign. Almost everything I got done, everything that worked, I simply did it and asked permission later. All the internal campaigning, the long memos and proposals and drafts and meetings, was almost entirely wasted.

And it was much, much too close.

Still, we won. And the country will be safer and better.

Jim Fallows at The Atlantic asked what people thought would happen if the Republicans lost this election. Here was my reply:

If the GOP does indeed suffer a defeat in 2012, renewing the party will be much more difficult than 1972 was for the Democrats.

The Democratic Party of the Nixon-Reagan era could look to compromise with Republicans on a wide range of areas because those areas — tax policy, military budgets, welfare reform — were things on which compromise was possible. The things that could not be compromised — civil rights, peace in Vietnam, and Social Security — were never under serious attack.

The Republican Party today regards sexual reregulation and religious belief as core to its identity. Abortion is murder, homosexuality is depraved, and the twin terrors of Islamic Fundamentalism and Humanism threaten to unhinge society. These are not issues on which compromise is possible. One can regard a change to the tax code or to welfare rules as unwise, and yet acquiesce in trying the experiment. One cannot acquiesce to what one considers murder and depravity.

The obvious parallel, alas, is to the New England resistance to slavery, 1828-1860. Though good people tried to find a way, there really was no path to compromise. If slavery is evil, Thoreau argued, you can’t sit by and regret it. If it’s not evil, Calhoun was right. Between them, there was no place for Dan Webster, and the memory of Shiloh meant that, for a century, US politics carefully kept to topics on which compromise was possible. The original nativism and know-nothing conspiracies receded. The anti-Semitism that was such a disaster for Europe never got a really respectable foothold; we had Lindberg and Father Coughlin but not Mosley and the Duke of Windsor. American Protestants stopped fighting over doctrine and stopped fighting against Catholics.

For a long time, it seemed that no compromise was possible on the integration of the South, and the Senate was organized to make such compromise unnecessary. That ended when, in 1948, Humphrey convinced the Democrats that segregation was no longer something that could be countenanced, that it had to end whatever the consequences for the party. And of course that did split the party and transformed the landscape of American politics into the world we know. (In the end, Johnson saw that the South could compromise on integration and still be the South: “Guess who’s coming to dinner?” might be a a bit of a shock, but if it’s Sidney Poitier and he’s a doctor, you could live with it and talk about the Dallas Cowboys.)

How does today’s GOP sit down for a nice dinner with Planned Parenthood, Sandra Fluke, Lena Durham, and Richard Dawkins? I used to know Republicans socially. My parents and aunts and uncles all did. I don’t anymore. Democrats and Republicans are beginning to dress differently, to wear their hair differently. Limbaugh really thinks that Sandra Fluke is a slut. You simply can’t have both of them to dinner.

In a real sense, Romney already is the Republican turn toward moderation. It’s untenable; you can’t defend the unborn one day, and promise to keep Roe v Wade the next. The only way Romney could moderate his positions was to be seen to lie, to convince people that he held contradictory opinions but would govern the way they hoped. There’s just no viable position for a potential nominee who is more moderate the Romney. As an intellectual exercise, one could imagine a Republican who supported immigration reform, a stronger social safety net, and overturning Roe and Griswold – but this would simply alienate the tea party while remaining unacceptable to almost all Democratic voters.

There might be scattered opportunities for the GOP, but I think this may be their high water mark, the first of a long sequence of bitter losses and painful memories, of choices between bad and worse. But I have a very bad feeling about this: I think it ends in a the televised battle on the California border between state police seeking to apprehend an attractive young physician on charges of capital abortion, and the California National Guard who are determined to save her. The old vineyard of the grapes of wrath is closer than we imagined, and the fruit hangs heavy on the vine.

The Development of Storyspace, by Belinda Barnet, in Digital Humanities Quarterly.

This article traces the history of Storyspace, the world’s first program for creating, editing and reading hypertext fiction. Storyspace is crucial to the history of hypertext as well as the history of interactive fiction. It argues that Storyspace was built around a topographic metaphor and that it attempts to model human associative memory. The article is based on interviews with key hypertext pioneers as well as documents created at the time.

Highly recommended.

I threw two weekday dinner parties in the same week. I’m never going to eat again

Two dishes might be worth a memo. First, I put together a soft drink for Kirsten, who is Linda’s 15-year-old Swedish cousin. Kirsten doesn’t believe in wine.

This is adapted from something Stephanie Izard did on Top Chef, which I watched while I was having my post-travel illness. Izard also used some pineapple juice, apparently, which might be gilding the lily. In any case, they were having a hurricane outside, so pineapples were not readily available.

Saturday night we went to Journeyman, renewing connections with Dave Gray, who is a very connected guy . Diana Kudajarova and Tse Wei Lim, who run Journeyman, cook the way I think I’d like to, and this is edging slightly (and aspirationally) to their style, as a student imitates the master.

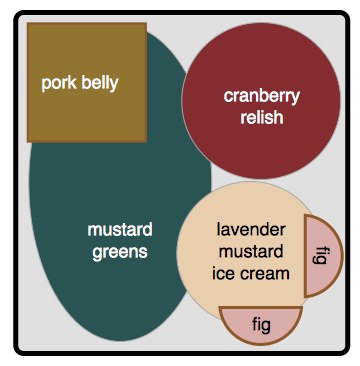

We start with a nice piece of pork belly. It’s cured for a week with salt, spice, and maple syrup. Then it was hot-smoked for three hours over cherry, to an internal temperature of about 155, and cooled. Before serving I cut it into 1” cubes, and finished them by deep frying them for about 8 minutes in hot canola oil.

Figs are figs. Cranberry relish is right off the back of the bag: 1 bag of cranberries, one whole unpeeled orange, 1 cup sugar, food processor.

I was making duck sausage (for duck burgers) for a different course, and after my trip to Spain I thought I might try rendering the left-over duck skin for a few crunchy bits. Turned out surprisingly well; save for the files.

The mustard ice cream is adapted from an everyday vanilla ice cream recipe. In the creme anglais, vanilla bean is replaced by a handful of lavender leaves, the sugar is halved, and for 2C of anglais I added 6T of seedy dijon mustard.

This isn’t exactly great for your diet, but there’s a lot going on. Pork and mustard, of course, playing along with very hot and very cold. There’s also sweet (the ice cream, the cranberry relish) and bitter and some umami. Fat and acid over vegetables: it’s a vinaigrette! And the cured, smoked pork belly is essentially bacon, served in an unusual form factor, and everything goes better with bacon.

I served this as second course, but it could work fine as a dessert, too.