Websci this year received a lot of work. One ninety eight submissions were reviewed By more than seventy program committee folk, And in the program we managed to find space For forty talks and more than forty posters By squeezing every minute,every meter, And plotting out the pecha kucha show I hope you’ll all enjoy right after lunch today. I emphasize we always separate The mode of presentation from publication. Some of the papers we thought best became Posters or short talks because we we thought They’d show to best advantage in a smaller space. So we might think ourselves well pleased, A happy conference, prosperous and strong. This year, you gave this conference many frights. We waited for your papers anxiously And feared too few would come, 'til at the end They all poured in at once, and more came late. The deadline for extended abstracts came And went, and papers still rushed in. Reviews Were also plentiful but very slow, Terser and more shallow than I’d wish. And so I take a moment here to ask You all to slow down all of your reviews, To water them and let them grow a bit. Move carefully but well beyond your comfort zone, And show your work. Tell what you understand And how. We do not care as much as you Just what you like — and don’t. We need to know More clearly what you thought about, and why. ❧ Disciplinarity is harder than you think. In school it seems to be for most A question of departmental boundaries, One that good-natured friends with ease Should overcome. Alas, this turns out not To be the case. Our disciplines Encode our rules of evidence, and worse Encode what we think good, and bad, and wrong. Last night, in fact, I was awake past two To settle one last vexing argument. Simple things like how we submit work And then review it raise question and tempers too. What seems straightforward in one field Another finds intolerably wrong. ❧ Whoever thinks a faultless piece to see, Thinks what ne'er was, nor is, nor e'er shall be.But still, my friends, this isn’t good enough. The writing we received is really far from good, Making all allowance for the fact That we all come from different states and fields. I don’t complain of trivial mistakes. I am myself a very sloppy writer, And almost every paper I submit Has missing words and blunders. It’s not these That makes our papers so damn hard to read, But rather imprecision in our choice of words And absence of concision in our prose. You need not hammer home the structure of your work If it's the same old structure we have read Since we were undergrads. But if you write About the antelopes that roam the Web It does behoove you well to know exactly what An antelope might be, and to distinguish them From beavers, boojums, snarks and ocelots. You need not argue ocelots are bad! We simply want to know how your ideas fit With what we all already do and know. Precise word use and thorough scholarship Are even more important when, as here, The audience is drawn from many disciplines. Our topics — timid, inoffensive, mild – Will seldom cause great outrage or surprise. The times are bad, the provost even worse, I understand how fear of a false step Can tempt us to tread light. But still, It’s not just me: a bunch of you sent mail To ask about the timing of your talk So you might fit it in your travel plans And rush away to give another talk. I don’t recall a single message sent To ask about a colleague’s Web Sci work, And when their talk might be. Why do we come To conferences like this? To please our dean? To earn a meager line on our CV? That’s not the point. I hope we come to learn To find the best of what is being done And thought about this complicated Web. So thanks for coming. Please enjoy the show; I look forward to learning what you all newly know.

Another delightful dinner at Guy Savoy’s Seine-side bistro. What could be better than an elegant neo-bistro named for booksellers? The truffled artichoke soup was everything you could want. The beef was perfect, its sauce tangy, its potatoes luxuriously smooth. The calvados could not be faulted either. This is not food with an argument, perhaps, just very good food, smartly presented. The wine was lovely, and with a name like Le Temps Est Venu, I suppose it’s got an argument somewhere.

And palmers for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, couthe in sondry londes.

Walking back from the Orsay, I noticed that we were at 42 rue du l’Université. Julia and Paul Child lived at 81. Why not drop by?

Actually, 81 is not particularly close to 42. Oh well.

by Alan Furst

Paris. 1938. An American movie actor sails over in the I’le de France, lent to Paramount by Jack Warner. He’s not entirely comfortable with this. Soon, German emigres and diplomats make him even more uncomfortable. Lovely sense of place and time and noir.

Unfortunately, the lines at the Orsay are very long.

Fortunately, for a modest charge, you can now reserve tickets that allow you access to entrée reservée downloaded to an app on your mobile phone.

Unfortunately, this isn’t actually true: you have to print the tickets.

Fortunately, my hotel is accustomed to this.

Unfortunately, the special entrée reservée merely lets you join the back of a very, very long queue of other people similarly equipped with advance tickets. This queue may or may not be shorter than the very, very long queue of people who do not yet possess tickets.

Fortunately, it was only an hour or so of waiting, and it didn’t rain, and the grand hall with its wildly unfashionable but wonderful sculpture is still terrific.

Unfortunately, the display area for pre-Impressionist painting is greatly restricted by renovation. A little is on display, more is on loan.

Unfortunately, the result of those long queues is that the Impressionist galleries are overflowing with crowds of inattentive tourists and crying babies and energetic pre-teens from the four corners of the world. This makes it difficult to appreciate, say, Whistler.

by Cory Doctorow

In Little Brother, Marcus Yallow’s high school world got blown apart when someone blew up the Bay Bridge. The panic was bad but the government response was worse, as the government used terrorism as an excuse to impose martial law. That crisis was resolved, thanks to Marcus’s clever hacking, but the Lesser Depression has gotten worse and worse and the government is still eager to use the Internet (and a healthy dose of torture) to control a docile populace. This sets the stage for Homeland.

Doctorow’s entry in Clute’s commendable Science Fiction Encyclopedia is, I think, exactly right: Doctorow is a thinker who uses fiction to explain an argument that mixes technology and politics. This has not been a formula for success lately, though of course it once worked well enough for Hugo and Zola and Shaw, for Dreiser and Dos Passos Sinclair Lewis. But it seems to me that Victor Hugo is the closest match to Doctorow’s aspiration; these are books of ideas first, with some dramatic tension to leaven the dough.

There’s plenty of leavening, and also plenty of info dumps. We learn a lot about police tactics, 3D printers, Burning Man etiquette. We learn how Occupy does public speaking without a microphone and how to manage a campaign Web site.

One thing we don’t learn much about is Marcus’s callow, feckless parents. Mom and Dad are useless. The parents of Marcus’s remaining school friends are no better; though his girlfriend’s parents are cool about his spending the night now and then, none of them does much about the government surveillance, harassment, and torture of their kids, and none of them takes much interest in finding a job for themselves or their grown children. Marcus does make a point of cooking nice family dinners to restore a sense of normality to the house, but his parents simply make appreciative noises. These kids grow up early. So does Katniss Everdeen, to be sure, but Katniss knows it’s wrong and it makes her sad and angry and she thinks about it all the time. To Marcus, absent parents are just the new normal.

Canadian-born Doctorow now lives in England, and his campaign subplot makes more sense for the UK than it does for the US. The story is set in a near-future that is even more recognizable than the terrorism-battered San Francisco of Little Brother. Our hero, Marcus Yallow, is now webmaster for a charismatic politician running an independent campaign for the US Senate. This candidate is clearly a progressive, but deplores the Democrats’ support for drones and detention and bankers. The Republicans are “just as bad.” This is arrant nonsense. First, the Republicans aren’t merely just as bad; they’re just as bad on these issues and they’re insane on many others, Doctorow forces his would-be Senator into false equivalence of the worst sort. The candidate worries about being forced by party discipline to vote against his conscience, but everyone knows that the Democrats have no party discipline. The candidate is running for the Senate: how does he propose to work in the senate? Of course he’s going to caucus with the Democrats.

When was the last time a Democratic senator was really hurt badly for going off the reservation? Remember: this is the party that held Hubert Humphrey and Theodore Bilbo together. Someday someone will pull off the trick that Lincoln did in 1860 and replace one of the current parties with a new one, but that’s not going to happen in a California senate race and, if it were to happen in the near future, the obvious candidate to play the role of the Whig Party is the GOP. This independent candidacy could make sense in Parliament; in the US, it’s a silly fantasy, and it feeds the right-wing propaganda that always blames the Democrats for Republican intransigence.

Doctorow will keynote Web Science 13 this Thursday May 2, in Paris.

A delightful dinner at Chez Lena et Mimile, high up in the 5th, with Prof. Everardo Reyes-Garcia, formerly of Toluca and now at Paris 13 where he has time for more research (hurray!) and terrific students.

This comfortable old bistro is now home to molecular gastronomy and to a disciple of Hervé This. I’m a bit worried that French resistance to the play of molecular experimentation may have worn them down a bit – much of the menu is fairly conventional, and even the tasty coquilles St. Jacques are fairly tame now. But the scallops were perfectly seared and the foam (remember foam?) was really well executed. And the wine could not be faulted.

Lunch at Café des Musées with some delicately smoked salmon — smoked meats in Paris this year seem to be very, very lightly smoked — and a faultless vegetable cocotte.

Hopping off the airplane and finding our hotel in the 5th, all had gone smoothly. Too smoothly: our room wasn’t quite ready. I wasn’t hungry but eating would be a Good Idea to help with jet lag, which is causing more trouble this trip than usual. We asked where might we find a light lunch.”

The concierge directed us to the end of the street. Not the restaurant at the corner. Turn right: two doors down. That one.

Now, that’s a a tasty salad complet to go with a nice dark bier. And Linda’s omelete was tasty, too.

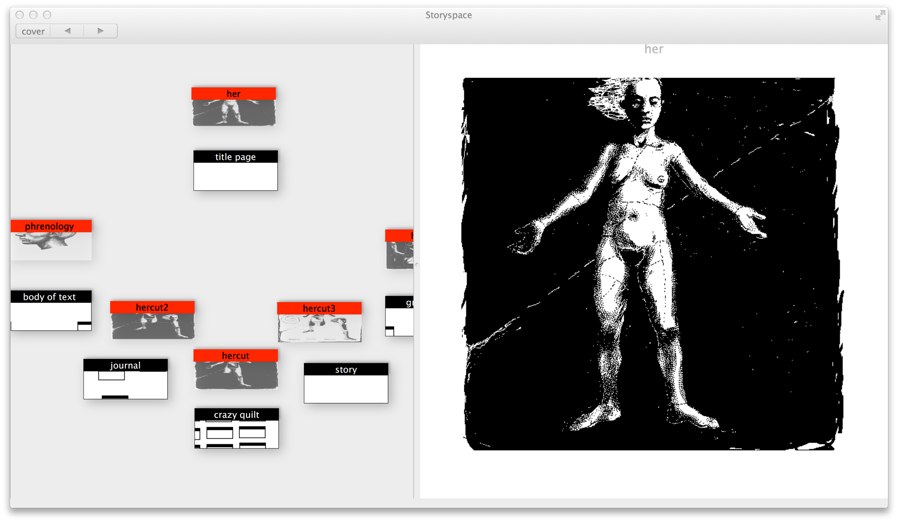

That’s a screen shot of a new prototype of Patchwork Girl by Shelley Jackson, running of OS X Mountain Lion.

We’ve got two separate projects building toward a new generation Storyspace. This is the first project, built on raw Cocoa with a fresh implementation of almost everything. Call that one “Hot Chocolate.”

There’s also an ambitious second project, built on the technology platform that Tinderbox uses. Twelve years ago, the first cut of that platform was code-named Hereford, so call this fresh implementation “Cool Cider” since cider, it seems, is the drink of Hereford.

Hot Chocolate will become the foundation for a generation of iPad readers for hypertexts written with Storyspace.

Cool Cider will become the foundation for Storyspace.

Now, what goes well with apples and chocolate?

by Geoff Cox and Alex McLean

Two distinct groups of people are interested in the aesthetics of computer programs. On the one hand, we have people who create software; those with taste and judgment will naturally hold aesthetic opinions and prefer the beautiful to the ugly. Opposed to these artisans, we sometimes meet a group of theoretically-inclined critics or "codewerkers" who compose things that look like poems but that ridicule the benighted corporate fools who make or use real software.

In Speaking Code: coding as aesthetic and political expression, Geoff Cox and Alex McLean are writing for the latter. The program code of which they speak is almost always either a hypothetical category too broad to be analyzed or a clever stunt ginned up in a dozen lines of perl. These toys are sometimes clever, but they have little to do with actual programs, and their creation has little to do with the construction of actual code. It is as if the authors set out to write about painting but, finding actual painters dead and actual paintings opaque, decide instead to analyze instead the movie actors who portrayed some painters. The actor’s version of Jackson Pollock might look like a painting, and it might be made from paint, but it’s not Pollock.

The book is filled with tiny little programs. Some of them run. Some of them simply look like programs and are meant to be read. The first example is written in an esoteric language called Befunge, and the general level of scholarship in this volume is reflected in the first footnote.

As an esoteric language, Befunge also breaks with the conventions of downward direction of interpretation through two-dimensional syntax [1].

[1] For more on the Befunge programming language, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Befunge.

Parts of this book are scrupulously sourced – for example, Cox makes some very nice distinctions between Lacan and Hannah Arendt – but the creator of the programming language that is the subject of the opening argument doesn’t deserve citation, presumably because the kind of mechanic or drudge who would actually write a compiler is obviously insufficiently human to deserve one. Elsewhere, Cox urges resistance to Javascript because "it is proprietary, indeed owned by Google." This point might be interesting, were it true. His footnote leads to a wiki page at LibrePlanet which links, in turn, to an essay by Richard Stallman; apparently, Cox misunderstood Stallman’s opposition to Gmail (a Google Web service) to mean that Google owns the underlying language. Stallman’s polemics against software property are briefly mentioned elsewhere in the book, but his actual art — the beautiful and immensely influential EMACS editor — is not.

It’s not just Stallman. You won’t find Kernighan here, or Ritchie. Bill Atkinsons’s not around, nor Bricklin, and there’s no joy for Bill Joy, nor does Lisa Friendly’s JavaDoc find a friend. You won’t find Sutherland’s Sketchpad, or Smalltalk, or The Demo. Knuth appears only for a cameo on literate programming. Ward Cunningham’s wiki was beautiful code (though modern incarnations are covered with ugly encrustations). Charles H. Moore’s FORTH was gorgeous. So was John McCarthy’s LISP. And there’s no hint of the work programmers do with Iverson’s APL and Wall’s Perl to express complex ideas in a tiny, tiny compass, a game as intricate as a villanelle and as delicate as haiku.

In fact, Reading Code seldom looks at any code that does something, code that might dirty its hands with actual work. Instead, we have things that look like programs and make pithy declarations about capital and labor. Every beginning student, learning that a variable name is simply a label and that the machine does not know or care what the label means, spends a day or two playing silly games.

for (teacher = every + fracking + grownup) { frack = you; }

There’s a lot of that here. And there’s some mild cleverness, like referring to a program that recursively deletes your Facebook friends as a form of (social) suicide. But none of it is really code, and a lot of it isn't quite as clever as it thinks.

The problem we face in thinking about code aesthetics is twofold. First, code is big, and the printed page is small. When we write about novels or epic poetry or a Collected Work, we assume that the reader is generally familiar with the work, that we are exchanging insights about familiar things. It’s not clear that MIT Press expected the audience for this volume to be able to read code, but there is no hint in the book that the authors expect readers to have any shared experience of it.

Second, code works. It does stuff. Its hands are dirty. This seems to unnerve the code aesthetes as much as machine aesthetics unnerved so many people in the 19th century. How could stone and steel be anything but ugly? Viollet-le-Duc had an answer, and Ruskin had another, and then Louis Sullivan told us that the tall office building "must be every inch a proud and soaring thing, rising in sheer exultation that from bottom to top it is a unit without a single dissenting line." Architectural beauty does not depend on ornament any more than delicious food depends on folding napkins into pheasants; to understand, we must simply have sympathy for things, their inherent tendencies and their purposes, their fabric and their fate.

What Cox and McLean overlook, alas, is that software aesthetics are in the midst of a profound revolution. For years, aesthetic discussion was polarized between two camps: those who advocated provability or at least mathematical rigor, and those who prized clarity. The mathematicians (also called “neats”) prized concise languages and intriguing formalism: LISP and Scheme, APL and Prolog. Their opponents (“scruffies”) prized structural clarity and expressiveness: Algol and ADA, C/C++ and Unix Tools, Java and Javadoc, Smalltalk. Neats wrote lovely little things; scruffies wrote exciting big things. That’s changed in the last five years in the wake of Design Patterns and Refactoring, Agile, and the tiny methods style. Today, scruffies still write large, but those programs are made up of lots of tiny bits, bits that look like the work of the neats. And the neats, too, can suddenly find a place for their work in the middle of a Web of small, loosely joined pieces. Spuybroek sees this in The Sympathy of Things, but there’s really not the slightest hint of it here.

Cox and McLean fancy themselves members of a radical left that abjures corporate control and detests "neoliberalism". In practice, they've gone all the way back to Versailles, dressing up as working folk and holding working-folk tools and cherishing clever little jokes that display their leisure-class status and superiority to work.

Iain Pears has a new hypertext fiction coming this fall from Faber.

Steve Johnson (the FEED guy) has a piece in Wired about why hypertext fiction failed. He thinks it’s too hard, and that people promised too much. People always promise too much about a new technology, style, or movement — or at any rate you can always pretend they did. Bzzzz. Next contestant!

Mark Marino thinks he’s part of the answer. Or something like that. He asks me not to be mean to him, so I won’t. I’m too busy writing Storyspace 3 and Tinderbox 6 and putting the final touches on Web Science 13.

Company One at the Boston Center for the Arts is staging She Kills Monsters, a nifty play by Qui Nguyen.

Agnes Evans (Paige Clark Perkinson) is a young but dull Ohio school teacher. Her parents and her geeky teenage sister Tilly (Jordan Clark – the actresses are sisters) died in a car crash. Cleaning out Tilly’s room, she comes across an obscure module that has something to do with D&D. She asks experts for help: what is this stuff? What does she want to do with it? Play it! And so Agnes the Ass-Hatted goes adventuring in her dead sister’s psychic wilderness.

This is clever: leaving an apologia in the form of a D&D adventure is crazy, but it’s just the sort of thing Tilly would do. The adventure leaves us plenty of room to play with identity (Tilly becomes Tillius the Paladin who does battle with, among other things, a pack of cheerleader succubi) alongside the redoubtable axe-wielding tank Lillith and the sveltely dangerous dark elf Kaliope. “Why don’t any of you know how to dress yourselves?” Agnes complains constantly about their improbable armor. She learns the answer, and much more.

At the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco, we saw this exciting new musical Stuck Elevator by Byron Au Yong and Aaron Jafferis.

It’s the 81-minute story of a Chinese pizza-delivery man who is stuck in an elevator in The Bronx for 81 minutes. This premise is great for San Francisco, where the show opens, and for New York, for which it’s destined, and also serves to build lots of interesting tension. How are you going to block a play that takes place in such a confined space? How, for that matter, are you going to make it dramatic – how are you going to get anyone else on stage? The solutions are ingenious, the songs are pretty good, and it’s a nifty tale.

A lot has been happening around here lately — especially Friday, where the Press Of The World was camped right down the street, tantalizingly out of reach. We’re safe and well.

by Alison Bechdel

Alison Bechdel’s childhood was difficult. All of them are. This long, profound, and beautifully-drawn comic explores the author’s relationship with her mother, and also with her several psychiatrists, three girlfriends, and Virginia Woolf. On the way, she engages the work of psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott with depth and sensitivity.

My father was an analyst. Almost anything about psychoanalytic theory will send me running for the exits, but somehow I found this work thoughtful and engaging and – for once – more focused on ideas than on theoretical fireworks. It’s also a relief that, through all the emotional discussions with mother and shrink, Alison’s sexuality is always taken as a fact, not something to be explained much less fixed. The book is technically masterful, especially when pulling two or three separate arguments across a series of panels without muddling them and without being bogged down in more allegory than the medium can bear.

by Benjamin Lytal

A reliable way to define the protagonist’s beloved is to give him or her no inner life. Adrienne Booker is beautiful and brilliant and loves to sing Mozart and Bach, the Beatles, and she makes loves to Jim Praley. This surprises and delights Jim, who has no idea what’s going on but who is not hard to please. A would-be poet without access to his own inner life, Jim makes a wonderful partner to Adrienne. They are young and attractive and the world is all before them. Of course, the world is mostly Tulsa.

by Lucy Knisely

A love-letter from a 20-something comic-book writer to her mother, couched as a book about cooking, eating, and coming-of-age. Knisely has a knack for expressive character drawing and a clever way with anecdote. Chapters are punctuated with two-page spreads that describe a recipe; these are neatly done and the recipes look reasonable; though she still believes the McGee-debunked myth that washed mushrooms get soggy, anyone who suggests serving a big bowl of sautéed mushrooms for dinner is fine in my book.

The most original chapter in this pean to tasty food is an intelligent piece on bad meals and on cooking for people who don’t really like to eat – two real problems that we seldom hear discussed.

The subject here – the confluence of food, family, and memory – could easily have collapsed into mere sentiment. What keeps Relish fresh is Knisely’s lively drawing, particularly her knack for sympathetic portraits of herself at various ages and her skill at drawing not the food, but the way people react to it.

This fascinating restaurant in San Francisco is likely a template for the way we’ll soon eat out everywhere.

The menu is divided in two parts. Most of the food is presented dim sum style: people bring trays or carts with small plates that you might like. There’s also a small list of “commendable” dishes that you can order. There are three savory pancakes — we had sturgeon and horseradish — and the eponymous CA state bird (quail) with provisions that include tasty pickled onions.

It’s an open kitchen and, as far as I could tell, all the cooks serve and most of the servers cook. You have the advantages of “chef’s whim” – the kitchen can send out whatever it feels like cooking – without the rigor of a tasting menu. The cooking is very, very impressive.

by John Connolly

Don D’Ammassa explained at Readercon’s The Year In Books that he found John Connolly in a grocery store. Visiting friends in a remote part of rural New England, D’Ammassa ran out of books. This is not hard to imagine, as he reads one or two novels a day, but booklessness is not something he is willing to contemplate for more than an hour or so. And so it was off to the grocery store to find the least-bad book in town. (Had his hosts nothing in the house? ) And there he found John Connolly.

In The Gates, we meet a young British lad named Samuel Johnson. He has a dachshund named Boswell. He has a distracted mother, an absent father, and unpleasant neighbors named Abernathy. Unfortunately, these unpleasant neighbors have taken to dabbling in satanic rituals. More unfortunately still, one of their rituals, assisted by the CERN supercollider, accidentally manages to open a portal to Hell.

No one will believe Samuel’s warnings, and demons turn out to come in surprising varieties, including one who discovers that he really enjoys driving a Porsche very fast. The book inhabits Terry Pratchett territory, which is not a bad place to be.

Ebert was the film critic of his era, one of the great critics of all time, and in a quiet way a leading voice of life on the internet. He showed how to live on the Web when everyday life was difficult. He had deep knowledge and deeper sympathy and boundless good humor; his last article, “leave of presence”, assured us he wouldn’t be gone long.

The balcony is closed.

by Sara Paretsky

Lotty and Mr. Contreras and the rest of the crew join V. I. Warshawski once more in this energetic and angry mystery at the sleazy intersection of fancy law firms, politics, and right wing broadcasting. We’re not that far from the mean streets of wartime Vilnius, and nowadays we’re never that far from the mean streets of modern Kiev, and both cast a long shadow over Warshawski’s South Side. It all starts in a disused Chicago cemetery when a bunch of schoolgirls stage an initiation and one sees a vampire. The book is superbly plotted and the writing has its moments, but something terrible has happened to Paretsky’s ear for routine dialog, especially when kids are in the room.

My first big programming project was a summer project in the gait lab at Rush St. Luke’s Presbyterian Hospital. I spent six or eight weeks there, building a graphics library for Tom Andriacchi that would take measurements of joint angles from experimental subjects and reconstruct where their legs were from moment to moment.

This was an exciting project, investigating the brand-new technology of replacement joints. Joint replacement was a big deal then; nowadays, people get new knees and hips and they’re quickly back on their feet.

I was thinking about that project this morning. I think my graphics library took a couple of months. Today, I could do a much better job in a week, and might be able to get a decent result in a hard day of work.

One reason is that I’m better. I spent a lot of time debugging the library, testing small changes in the hopes that each small change would make things right. The trigonometry quickly got gruesome, so there were plenty of opportunities for sign errors everywhere, but scattershot debugging of a mucked up system almost never succeeds. And I didn’t yet know about separating model and view logic, since Smalltalk-80 was well in the future.

One reason is that the tools are better. I remember that I lost a week on a compiler bug in which FORTRAN’s call by reference semantics permitted me to redefine the constant number “1” to a different value. Compilers still have bugs, but nothing as low-hanging as that!

This library would have been much nicer if it had been written with some object-oriented encapsulation. But object-oriented languages were only beginning to get off the ground, and I still hadn’t discovered that the Computer Science literature was much better than the (already dismal) Information Technology literature.

The big reason is that, now I have a computer. This library had to be written and debugged on a shared departmental minicomputer, and computer time was a scarce resource. You’d sign up for a brief slot, and try to get as much done as you possibly could. Other eager programmers queued for any minutes you didn’t need.

Of course, everything was memory constrained then, and everything was terribly slow. So edit-compile-run cycles took forever. There was no debugger; just diagnostic writes. In one long day of test-driven development on my MacBook Pro, I’d probably get more compiler-edit cycles done than I did in the whole summer.

It’s interesting that in this fairly-conspicuous restaurant with a lovely open kitchen, half the brigade are women.

Wonderful charcuterie, and terrific mushrooms with snails and stuffing and not too much garlic. A fine spring navarin of lamb. Tasty roast duck. And an eclair au chocolat that’s not kidding around.

by David McCullough

David McCullough recounts the adventures of a century of Americans in Paris. In the 1820’s, Americans came for the world’s best medical training ands the world’s best art training. At the century’s end, they came for the fashion and for the food, for glittering nights, and for the world’s best art training. In between, McCullough reconstructs the fascinating, forgotten story of the American Ambassador who determined that it was his duty to remain at his post through the siege of 1870 and the Commune and whose rediscovered diary provides vivid insights into a time whose brief turbulence seemed likely to continue forever.