At Heathrow, I saw a new book, Ian McEwan’s Sweet Tooth. I saw it again at Oxford Books in Kolkata, and it seemed to me that Oxford Books is a fairly good bookstore growing in what must be difficult soil for which I’m sure it pays astronomical rent. So I bought the book, for 550 rupees.

The bars of Alcalá de Henares have a charming custom of giving you a plate of something tasty with your beer or your wine. On the one hand, this is hit or miss. On the other hand, it’s a ton of fun, and very tasty indeed. So I’ve been sitting in corners of Tempranillo and Balcones, sipping beers and wines, and munching tasty tapas. (The cook at Tempranillo really knows what she’s about, and she’s reaching for the stars: tomato froth with sausage flecks and — I think — shaved dates.)

So, I’m reading the new McEwan, and it’s proceeding as one would expect of McEwan: intriguing, weird, and with an interestingly flawed woman at the center of everything. And then I came across this sentence:

He turned out to be a tender and considerate lover, despite his unfortunate, sharply angled public bone, which first time hurt like hell.

And I knew I’d read that before. Had I managed to become my parents, who used to buy Agatha Christies that they thought were new and discover, 150 pages later, that they’d read them ten years ago?

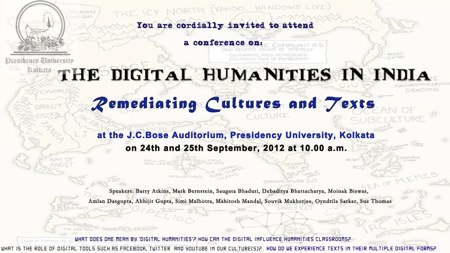

Nope. Turns out that passage was published in the New Yorker a couple of months back. I can’t check now because the WiFi at the Residencia isn’t quite up to actually wifi-ing. You can check, as John Cayley pointed out in his keynote this morning, by Googling, just as I did. Cayley advocates resistance; I'm sympathetic but, before we march to the barricade, I’d like to hear a plan.

The front door here is the best door I’ve seen in years, and they lock it at 8PM every night. And so when you come home, you have to knock using this great loud Wizard of Oz knocker which wakes the entire neighborhood, and then a guard comes with a key about eight inches long and uses that key to unlock about twelve pounds of 17th century ironmongery and let you in.