Joss Whedon endorses Romney as the candidate whose policies are most likely to bring on the zombie apocalypse.

This well-made spot is the future of television.

Joss Whedon endorses Romney as the candidate whose policies are most likely to bring on the zombie apocalypse.

This well-made spot is the future of television.

If these people triumph, science — or any kind of scholarship — will become impossible. Everything must pass a political test; if it isn’t what the right wants to hear, the messenger is subjected to a smear campaign.

Paul Krugman on the Republican attacks on statistician Nate Silver.

Rough but eloquent: my first five years.

I was born in August of 1943 in Shanghai, China of Russian émigré parents during the Japanese occupation of the city between the two revolutions , the Russian and Chinese.

David Allen (Getting Things Done) sits down for an in-depth interview with James Fallows from The Atlantic. This is the auspicious start of a a new series of features.

I’ll predict an Apple setback if you need more eyeballs,

It’s so much fun to aggravate the bourgeoisie.

Manipulating stocks like an

Internet rock star

You can be a biz-tech writer just like me!

I’m reading the new Adam Gopnik, The Table Comes First . In a chapter on wine and wine-writing, Gopnik repeats the off-told story of a study demonstrating that even experienced tasters, when tasting blind and blindfolded, could not distinguish red wine from white?

I thought that had been debunked. And, seriously, can it possibly be true? I can imagine that some red wines might possibly be mixed up with some white wines, but that isn’t what we mean here.

I’m not very skilled nor very knowledgable about wine, and my palate is not particularly fine. Still, I’m confident that I could reliably distinguish between pairs of distinct wines without seeing them or their labels. For example:

One has tannin, the other doesn’t. One has sugar, the other doesn’t. If you can distinguish apple cider from unsweetened black tea, you ought to be able to tell these apart. Or, take another pair:

One has lots of butter. One has lots of pepper. They’re both rich wines with lots of body, but I can’t imagine getting them mixed up.

First, the wines themselves tend to jump up and wave flags. Ones says, “I’m sherry!” If you opened a bottle of sherry and you got a light-bodied wine with grapefruit notes, no residual sugar, and not much finish, you’d be raising your eyebrows or summoning the gendarmes.

Now, I can imagine finding pairs that would be tricky. White wines with tannin. Light-bodied, fruit-forward reds, paired with big whites. Off-beat grapes. So, sure, I can believe you could set up some pairs that even experts would find puzzling. But can anyone confuse the common cases? “One of these is a typical Hermitage; the other is a Chablis. Can you distinguish them?”

Web Science 2013 will be in Paris next year, May 2-4. It’s going to have some excitement:

Keynote by Vincent Cerf. Colocated with CHI and Hypertext. Lots of other great stuff. I’m program chair.

There’s been a lot of chatter lately about character and the New England Patriots. When Tom Brady was just starting out, just as the Patriots were beginning to be a good team, they won a disproportionate number of close games. Nowadays, they lose a disproportionate number of those close games. Does this mean the Patriots lack character?

No. I think it means the Patriots are good.

Tom Brady was was a 6th-round pick, a backup pressed into service who worked out fairly well. The Patriots back then were a historically bad franchise, working its way toward respectability. Inconveniently, they’d just lost their starting quarterback, who was expected to go to the Hall of Fame.

In that era, sometimes the Patriots would get blown out, and sometimes they’d hang in and make it a close game — and, more often than not, they’d win at the end. If an inferior teams is close, that means something is wrong with the superior team’s model. Either they’ve got a mistaken assumption (e.g. they think Tom Brady is Carson Palmer) or they’ve got some injuries, or they’ve got an unexpected matchup headache. If the inferior team is already over-performing and they’re close in the fourth quarter, there’s every reason to think they’ll continue to overperform. This isn’t momentum. It’s merely the expectation that the game is likely to continue to unfold at the end as it’s been unfolding all day.

If a team is superior but the score is close, that still means something is wrong with the superior team’s model. If you’re the Patriots, you’re suppose to blow out the Jets. If it’s a one-score game in the fourth quarter, then we know that something has already gone wrong. And, if things have been going wrong, they may well continue to go wrong.

What we don’t consider here is random fluctuation. The good team dominates play, but loses three fluky turnovers in the first quarter. The football bounces oddly, and the team that should be up 35-7 at the half is, instead, down 10-28. The good team may well pull it out, but this lopsided contest is almost certain to go into the books as a "close game".

Flukes happen, but I suspect the majority of close games turn out to be close, in part, because some unexpected strength or weakness emerged. The superior team’s quarterback doesn’t feel great. The bad team has unexpected success running some sort of crazy screen. The bad team’s replacement quarterback turns out to be Tom Brady. The good team’s backup nickel back just can’t cover the bad team’s slot receiver, and there’s no one left on the bench.

Above all, selecting for close games biases your sample. If you look at “close games” when you’re not very good, you’re selecting games where things have been going unexpectedly well. If you look at “close games” when you’re a very good team, you’re selecting games when things have been going wrong. And, if you take a bunch of games where “things haven’t been going well,” it’s not surprising that you lose a disproportionate number of those games. Character has nothing to do with it.

Cool new Amazon Single: Michael Ruhlman on how we became a food writer, a great portrait of two young artists, committed to each other and determined to stay with the muse even when the muse seems inconstant. Main Dish

.

I was waiting to see whether I had malaria, or cholera, or influenza, or something else. I was not going to get much done. So I watched a season of Top Chef on my iPad.

These were the first reality TV episodes I’d ever watched. Some observations:

I was out of commission, flat on my back, and going nowhere. I had finished Insurgent and quite liked it, and so I was lying in bed and shaking with chills and wondering where I had put volume 1. As it turns out, volume 1 was on my iPad, just like volume 2, and so it was easy to spend the day revisiting it. And, while in principle that day might have been more profitably spent with, say, Eagleton’s After Theory, I wasn’t sure that the fever dreams of critical theory would mix well with the fever dreams of fever.

The book holds up better than I had feared. The pacing of the opening is superb on rereading, and the boot camp sequence is wonderfully done. There’s nothing much to learn from the romance, but we don’t usually read about the love of a pre-teen girl for a boy two years older in order to seek instruction or wisdom. I’m not sure I like the rest of the plotting, and I think Roth is so good at building worlds that she destroys them before actually putting them to use. This is wasteful and unsound, but I suspect that the great Moral of this series is that invented worlds are a renewable resource.

In 1972 Serena Frome, fresh from Cambridge, spends a summer with her aging donnish lover. At the appropriate moment, he passes her along to MI5 where she files reports and types bold memos about which her superiors soon have second thoughts and which they will never send. In one memorable pinch, she’s sent to clean a safe house in Her Majesty’s service,.

And then, of course, she is given a shot at responsibility: recruiting a young novelist in a program to steer “culture” in directions that will promote Britain in the Cold War.

Ian McEwan here channels Le Carré, and does it remarkably well in this story of a spy who never quite gets out into the cold. He then turns the story on its head and lets it hare off in the way McEwan stories (Atonement, Amsterdam) will do. As Chesil Beach seemed to be a story about sex and turned out, on second thought, to be a story about art, this is a story that is not chiefly concerned with what its narrator thinks is her obsession, nor yet with the fate the reader fears will ensnare her.

About 12 hours after I took my last anti-malarial pill, I came down with terrible chills, fever, nausea, and the whole nine yards.

I’ve been flat ever since. I seem to be gradually mending, though; thanks for your patience.

This is volume two of a projected trilogy that starts with the excellent Divergent. Like Hunger Games, this young adult romance starts from a schematic premise — a dystopian ruined world that is rigidly organized along the lines of personality tests — and accomplishes surprising things. This is not the book that Divergent was, but few books are.

Tris Price, who says she is 16 but whom we understand to be a good deal younger, was born to abnegation and born for dauntless: her parents were members of the Abnegation faction but, on Choosing Day, she chose to join the Dauntless faction. Rejecting her parents’ beliefs was tough. Winning acceptance in her new faction was brutal. And now that she has gained that acceptance, now that she is a member of society, the whole thing has fallen apart and the whole known world (which encompasses central Chicago and perhaps some of Lake County Illinois) is falling apart as the factions fall to war.

Of course, there is a young man in the case, and that young man has problems — not the least of which is that Tris insists on setting tests for his love that no one could pass.

A misfortune of Roth’s schematic premise is that Tris is a Romantic heroine in both senses: not only is this the story of her awakening to love, but this is the story of heroism to which, and for which, she was literally born. She triumphs because of her intrinsic wonderfulness, and since Roth is doing SF, we’ll eventually learn that this is not an accident.

Some details annoy. The story takes place in a nicely-drawn Ruined Chicago, but too much of the geography is either unclear or wrong. It sounds like Erudite Headquarters is the Old Public Library, which makes lots of sense. But the description actually sounds more like the Gage Building, or maybe the Metropolitan Tower beneath its Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. Or is it the Santa Fe Building? The choice doesn’t matter (although details of each building could lend resonance to certain scenes if you let them), but the lack of specificity blurs what would otherwise be a very nice sense of place. Similarly, there are lots of trains, running endlessly along ancient tracks, never stopping. Dauntless use those trains to go places. The homeless live on them. But these don’t seem to be running on tracks we know; why, before the disaster, would Chicago have torn up all its transit and replaced it with new transit? One suspects instead that the author assumes there’s a train that goes wherever her characters need to be.

Still, Tris is an impressive young lady. She’s been through a lot. So has poor old, beat-up Chicago. It’s time to see what happens when we move out into the larger world. The name of volume three has not been announced, but surely it’s bound to be Emergent?

The four Macdonald sisters appeared at first to be completely unremarkable Victorians, daughters of a long-forgotten Methodist preacher. One married a successful ironmonger. One married an artist from a fairly good family, and another married an artist from no family at all. The fourth married an art teacher.

Or, in other words, one sister was the wife of Burne-Jones, another was married to the head of the Royal Academy and of the National Gallery. The third was Rudyard Kipling’s mother, and the fourth was the mother of Stanley Baldwin, thrice Prime Minister. But these were not the Peabody sisters, excelling their peers in reading and feeling, nor were they the Mitford girls, awash in a sea of wealth and beauty. They had scant money and none of their talents seem exceptional, and still things turned out as they did. Flanders explore the story of their interconnected lives, trying to discover the answer to the unknowable question: what made these seemingly unremarkable sisters the focus for so much success?

I like the idea of tapas. Not so much the “small plates” theme we have received in the US, which emphasizes lots of choice, but the (apparently) idiomatic style in Madrid, where you order a glass of wine and they bring you something like this.

Sure beats pretzels.

In Madrid, I spent some very pleasant hours at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. It’s an impressive collection, amassed by the Baron and his wife. The collection includes at least three of his portraits, and at least two of his wife. The one by Lucian Freud is pretty good.

A lot of the museum’s collection isn’t in the museum. The paintings are elsewhere, and they’re replaced by nicely printed little signs boasting of the prestigious places to which they are on loan. In some rooms, seemingly half the paintings were on vacation.

The remaining collection is nothing if not cheerful. There’s a Holbein of Henry VIII, looking almost a cheerful as the baron. There’s a brilliant big Sargent duchess, and an even better little Sargent Onion Seller in which John Singer is playing with a dark palette to very fine effect. There’s a nice wall of El Lissitsky, who looks best in quantity, and a single lovely watercolor by Winslow Homer, whose work does look all the better on its own.

There are three Chagalls, seemingly chosen for the sparsity of recognizably Jewish imagery. There is no Millais, no Anders Zorn, no Kollwitz. Everything is cheerful and pleasant and there’s hardly a hint of the guns of August or Hiroshima, Auschwitz or Berlin.

After some hours, I was thirsty. I sought out the cafeteria, but it’s situated outside the museum to attract patrons fron the street. There was only an hour before closing time; I decided I’d rather look some more. So I returned to the gallery.

But I couldn’t find my ticket. And the guard was unmovable (and rather rude): I must either find my ticket or pay another nine euros for the privilege of the remaining 40 minutes of viewing time.

I did find my ticket and spent much of the remaining time with John Singer Sargent and that lovely onion seller. It’s probably good to know what the Thyssen is saying: we very much want your money and your adoration, and we very much want not to be disturbed or distressed by the unpleasantness around us.

The gallery did not immediately offer to comment.

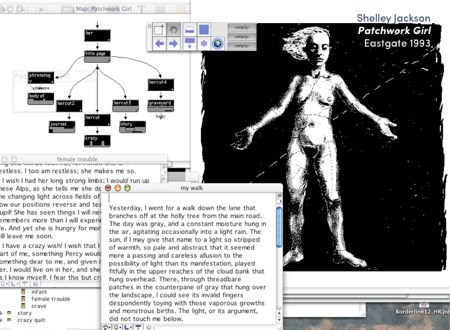

In my talk at Alcalá de Henares, I looked to the future of classic hypertext. The future of serious writing lies on the screen, and the link is the most important new punctuation since the invention of the comma: we know this. The iPad is important: we know this, too.

Preservation is important, and tricky; this was the core of Fernando Flores’s opening talk about ePublishing 2.0. Social media makes manifest the social construction of taste; this was the core of Susana Pajares Tosca’s departure from the ivory tower.

My talk explored old hypertexts in new environments. A lot of what we talk about — the demise of HyperCard, of Director, of Flash — has been talked out; either this is your problem, in which case it’s time for you to do something, or it’s not, in which case there’s nothing more to say. Storyspace 3 is my problem; people listened attentively, said nice things, and nobody asked a single question about performance, architecture, implementation, budget, design, typography, packaging, distribution, or censorship for the remainder of the conference.

One key point about the iPad and links has not, I think, been widely discussed. Before the iPad, we used a mouse or a trackpad; on tablets, we touch. We have been talking since the beginning of tactility, of words that yield.

But there was one thing we had forgotten.

When we are touching, we are not reading. And when we are reading, we are not touching. When we are touching the surface of the tablet, we cannot read what appears there because our finger is in the way. And, when we are not touching that surface, we do not interact. We might be making a choice soon, but we are not choosing now. The tablet alienates us from the link.

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The day is early, we have many lessons to learn, and we can only learn those lessons by building systems and using them. But the very directness of the tablet, the disappearance of the device between ourselves and the work, poses a new rhetorical and stylistic puzzle for the hypertext writer. This is an urgent question of craft that we should be discussing, one far more pressing in my view than embedding clever puns in your java source.

Arthur Vanderbilt says some very nice things about The Tinderbox Way.

I have been a software engineer for twenty years and was a software aficionado before that and have always been a lover of books, so it is much gravity that I say: this is the best book about software that I have ever read.