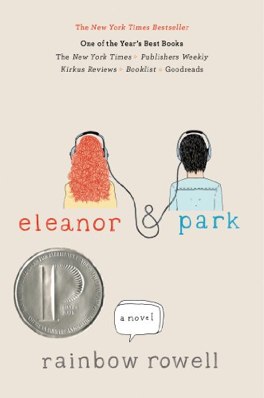

Eleanor and Park

Less ambitious and less accomplished than Fangirl, this is still a fine story about two kids who meet cute under difficult circumstances.

One narrative spring that drives the story is a crucially withheld bit of information: something is terribly wrong in Eleanor’s household. Rowell dismisses the convention suspects – marital discord, money, sexual abuse – unconventionally: Eleanor has trouble with all these, yes, but they’re not the real problem. Her stepfather beats her mother, Eleanor daren’t bathe when her stepfather is home, at sixteen she’s been thrown out of her house at least once before. All five kids share one small room. Eleanor’s home has no phone, and she literally doesn’t own a toothbrush. But these, it’s clear, are but the trappings and the suits of woe: something else, something darker, is the real problem.

Indeed, the extent of the family’s poverty embedded in a 21st century suburban setting is itself a striking narrative choice. The trappings all read 2008, but the circumstances sound like the lower East Side a century before. Indeed, the name “Eleanor” peaked in popularity around 1920, when it was about ten times more common than it was when our heroine was born.

In the end, the story is a love story for the mundane, troubled, old-fashioned American family. Eleanor’s boyfriend, Park, is the son of a Korean war veteran and his Korean wife. They don’t have much, but they have lots more than Eleanor. They don’t get along especially well – Park is convinced that his father loves him but doesn’t really like him, and Park is not wrong. From Eleanor’s perspective, it’s all pretty great.