The short story lived on – lives on – as a way to write fiction because teachers need to grade student work, and nobody really wants to read forty student novels. People seldom buy short stories – not even in collections: not, in any case, if you compare their audience with the audience for novels, much less television screenplays.

The same concern poses a challenge for new media, a challenge that distorts the literary landscape. I’ve never been completely convinced by Janet Murray’s contention that digital media are intrinsically encyclopedic, but many writers have been convinced, and their teachers don’t want to read a whole encyclopedia before handing them their A-. They especially don’t want to read a different encyclopedia for each of a dozen or two dozen students. And if, as is increasingly common, the instructor is an adjunct or a teaching assistant, they especially won’t want to read all those encyclopedias for $100-$300 apiece -- not with a couple of dozen class meetings thrown in.

But how can we create small, gradable new media works?

One approach, digital storytelling, focuses on crafting 3-5 minutes of personal memoir. There’s not much research to do: you know your past. Cinematic convention provides a narrative framework, and the miniature compass precludes most problems of plot and story.

Another approach involves poetry, especially poetry that explores the embodied nature of language beyond the familiar realms of meaning. Ceci n'est pas une pipe.

We might also mention social media performances like Jennifer Egan’s “Black Box” and miniature puzzles like Winter Lake’s Rat Chaos. These can be small because they’re elect themselves superior to story, much as so many new media poems elect themselves superior to meaning. They’re about themselves and their medium, which is a fine thing, and which allows them to be small. I doubt this is a lasting solution.

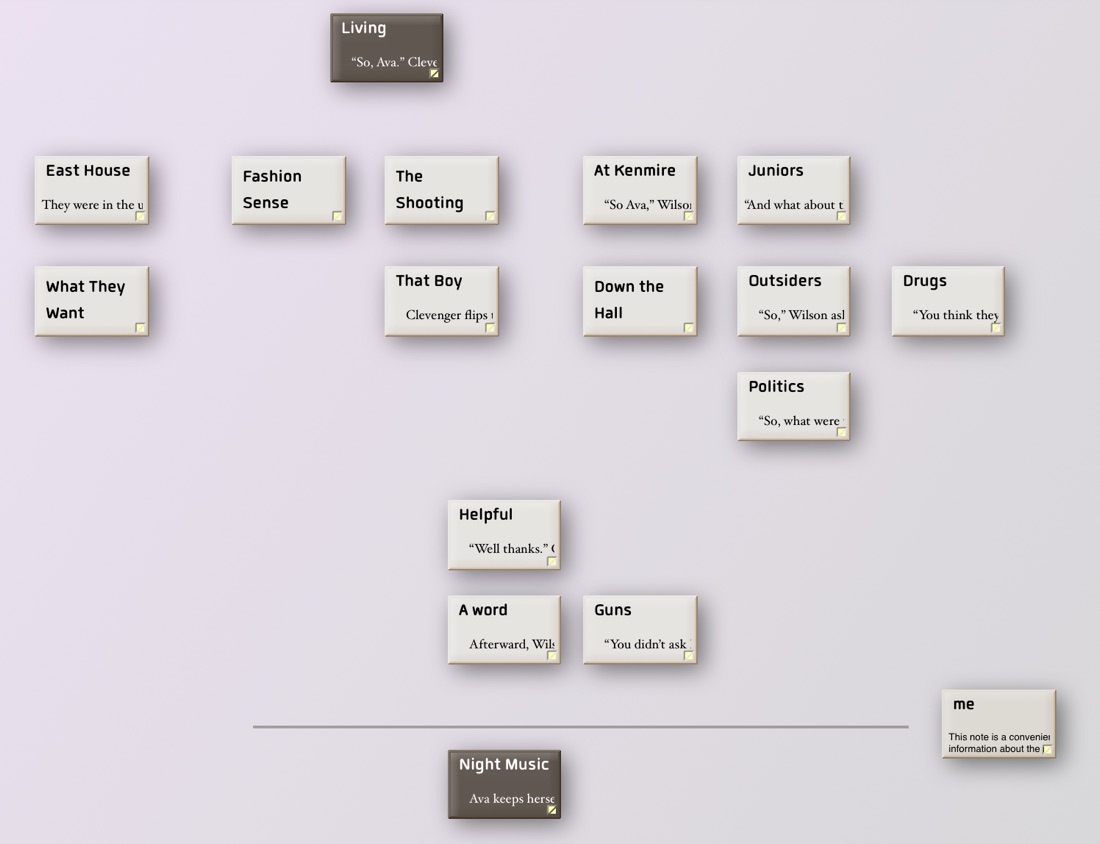

The hypertext short story has been attempted quite a lot, and has succeeded occasionally. Mary-Kim Arnold’s “Lust” and Kathryn Cramer’s “In Small and Large Pieces” come to mind, though Cramer’s work isn’t all that short. “A Dark Room” is that short, and fills itself out through engaging the reader in a trivial side game, something we tried, wrong-headedly, with Sarah Smith’s King Of Space. Geoff Ryman’s 253 is large, but perhaps need not have been; 253 is not the perfect cast size, it’s just the number of people who happened to be on that particular train.

21st-century hypertexts have tended toward large lexia – chapter length lexia in Iain Pears’ Arcadia and short chapters in Paul La Farge’s Luminous Airplanes.

The problems of hypertexts that are small enough to grade and yet large enough to take seriously, to teach us something we want to know, to be held up as examples in conferences and to be discussed by weblogs and journals, is real and pressing.