Here’s another part of what I’ve been working on: an approach to painterly hypertext. I want to suggest that it would be interesting to let go of some details of the way scenes are rendered in fiction, much as Impressionism sought to let go of some details of the way scenes are rendered in painting.

Let me tell you about a party.

Lady Daphne Laplace surveys her morning room, populated this afternoon by many of the guests she’d invited to this August’s party at Brecon Park. Outside, the splendid African sun shines down on her splendid green lawn, turning her elder daughter Mary that splendid shade of nutty brown she gets each summer. Mary herself has invited a lovely group of young people, all of whom will be heading up to Hill Academy in a few weeks for their final year before University. Mary is not to be head girl, as Lady Daphne had been in her day (Orie was a prefect at Marlton but no husband is perfect) but Mary has taken the blow well, and the headmaster’s surprising choice – an indigent but charmingly spiky young lady named Polly Xena whom Mary has invited and to whom Daphne has assigned her most patient and tactful maid – seems to be a acclimating well.

On the whole, Lady Laplace thinks this year’s party is doomed. It is not her fault. Last year’s party was very nice, the year before was terrific, and next year, perhaps things will be easier. Right now, everyone is on edge.

A big part of the problem is that the young people are having a very good time indeed, and their parents don’t quite know what to make of that. From her Head Girl days, Daphne has always been expert at the real mystery of house parties: who is fucking whom, and why. It’s all very well to understand that the kids are grown up now, and most of them are gorgeous, but it’s still very odd. The Hunters both seem especially edgy – Amy’s a dear, though underneath she’s every inch as middle-class as her parents – and poor old Marlow Randolph seems terribly preoccupied even though his girl Cassie (who has been very odd ever since her mother, poor Heshie, died) appears to be sleeping alone. Mary’s given up her friend Mason West – as prefect he belongs with the new head girl if she’ll have him – and Mary is being a sport about it. Daphne suspects that she’s sporting with Jacob Demarr, who is gorgeous and charming and captain of the ball team, though his father is just an administrator of one of the Senneterre’s estates. Daphne reminds herself to have a talk with Mary about the perils of sex with the middle classes.

The political climate isn’t ideal for a party, either. Orie’s been Minister of Culture for more than two years now and has been having a ball, but no government lasts forever and Daphne can see that they’re all nervous about the coming session. They always get like this, afraid that if once they lose they’ll be cast out forever. Minister of Culture is nice, yes, but it’s not everything, and one can’t move up until you’ve moved out for a bit. She’s tempted to ask Marlow to have a word with Orie, but Marlow himself has been more thoroughly out of sorts than she’s seen him in ages – far worse than when his own Ministry was tottering. Lord Randolph keeps going on about the rebels in the hills.

There have always been rebels in the hills: that’s what hills are for, and the rebels give the Army something to do.

There are the usual tensions, of course. The Hunters have never liked the Wests, perhaps because in their wild youth they liked each other rather more than was prudent. Their kids seem to like each other fine; that’s something, anyway. The Cormyns don’t get along – they never have – and Aspen Cormyn is constantly asking advice about anything that comes into her head from anyone who happens to have a title or two in the family. Poor Grenton, the butler here at Brecon, is overstrained by these parties and never hires enough help: Daphne is sure that she’s never laid eyes on the fellow passing those cheese pastries (remember to praise Mrs. Benson), and even for an informal Saturday afternoon, serving in a chef’s jacket and army boots seems a bit much. She won’t mention that to Grenton or to Jackson, the housekeeper; they notice everything, anyway. No doubt there is some unprecedented crisis in the kitchen.

OK: I told you about the scene. But maybe that’s not the best idea. Perhaps we should show this stuff, carry some of it in dialogue.

Where do we begin? With poor Lord Randolph, worrying about the rebels and telling any man who will listen what he’d be doing if he were still Prime Minister? With Aspen Cormyn pestering Vic Senneterre for advice on managing maids and daughters – subjects about which Vic has seldom spared a thought? With poor butler Grenton, dragooning some messenger sent to find “Colonel Pasternak,” who is not here and who is not expected, into serving as an extra footman because, if the man must be underfoot, he might at least be of use? Or outside with the kids as they joke and play games and figure out their sleeping arrangements?

Where do we begin? Who speaks first?

The received wisdom holds that this question has an answer, that if we write and rewrite, edit and revise, eventually we will arrive at the one true dialogue, the dialogue the rings true. Or, if we can’t find the right answer, we’re just not good enough.

But perhaps it doesn’t matter. They’re all going to get a chance to talk, we’ll meet them all eventually. Perhaps one sequence is just as good as another. We can just write it one way, and then perhaps convince ourselves and the world that this is the one true way.

My very bad sketch of a sidewalk scene in Provincetown.

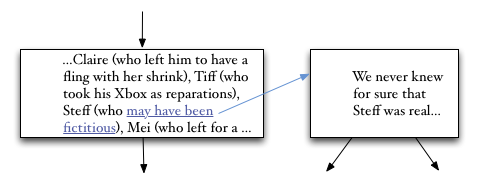

Sculptural hypertext could let us write this dialogue in all the ways it might work. We write some speeches and some exchanges, perhaps some descriptive passages as well. We add just the constraints needed to keep things coherent: the kids are outdoors, the adults are not, and so kids talk to kids and the grownups talk to each other. Perhaps we add some constraints to keep the discussion on topic, but maybe we don’t; maybe it’s that kind of party.

What the camera saw. More information, more accuracy, but also less.

Instead of trying to get the dialogue sequence right, we’re accepting any sequence that isn’t wrong. Moving from the morning room to the lawn without transition is wrong, so we won’t do that. Letting one character drone on without interruption is wrong; we won’t do that, either. But starting with Lady Daphne is fine, and starting with Lord Randolph would be fine, too, as far as I can see: we’ll try it all and see what works and what doesn’t.

We could start outdoors with the kids, or below stairs where the cook and the butler are coping with the current catastrophe, or we could start with the irritating Aspen Cormyn or with our patient and witty hostess. Let things play out. If we notice a bad combination, we’ll prohibit it. If we need more ways to move indoors and out, we’ll write them.

In painting, it’s not always necessary to specify everything. Perhaps it’s not necessary in hypertext narrative, either.