Doubling The Anchor

I’ve been writing about Getting Started With Hypertext Narrative lately, slogging out my minimum daily adult requirement of a couple of thousand words in addition to my customary duties, and I’m finding there’s a ton we don’t know. Here’s an example.

Imagine that we’re in the middle of a narrative sequence; default links (pressing Return, using the Next button) got us here and default links will lead us forward. But we could pause here for a bit more explanation, a story inside the story.

Let’s say we’re with a bunch of college friends waiting for brunch at a bar near Clark and Diversey and we’re talking about our friend Howard, who is late again. Howard is often unlucky in love.

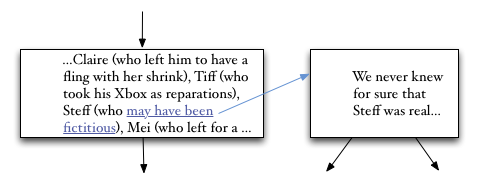

Since Barbara, Howard had dated Claire (who left him to have a fling with her shrink), Tiff (who took his Xbox as reparations), Steff (who may have been fictitious), Mei (who left him for a job in Palo Alto), and Cassie (who left him to dig dinosaur bones in Idaho after ‘borrowing’ a grand from Amy and $2500 from Bob). Howard told us about them in excruciating and embarrassing detail every Sunday, but we seldom saw them. After Cassie, none of us was that eager. After Cassie, who could afford it? But Barbara, that was a hell of a story.

We’ve got an optional club story, a useful supplement we can include for the benefit of patient readers, but which we might omit if tonight we’re in a hurry. We offer a text link to the beginning of the story, and perhaps put a guard field on the text link just in case we’ve already told that story.

The reader’s first question when she sees a text link is, “what does this offer? After following a text link, the reader’s first care is to confirm their theory of the link and, if their theory proves to be mistaken, to discover an explanation consistent with what is actually there. This is the core of the first great paper on hypertext writing, Landow’s “Rhetoric of Arrival and Departure” paper from Hypertext ’87, so we’ve known that much for a long time.

When writing this sort of hypertextual club story, how do we handle this problem? The destination of the text link should typically repeat the link anchor. The repetition need not be literal; we can restate, extend, paraphrase, parody, or invert the link anchor. We can turn the link anchor into a title, or change it from exposition to dialogue. We can occasionally defer the restatement, and sometimes we can omit it, but the restatement is part of the grammar of this kind of text link.

But where is this written? I’m quite certain this is a rule of craft, and like all rules for writer’s it’s made to be bent and resisted and it’s fun to discuss. But for the life of me, I can’t think of a place I’ve seen this stated. It’s not in the Nanards’ “Should Link Anchors Be Typed”, it’s not in “Scripted Paths,” it’s not in “Patterns of Hypertext” or “Canyons, Deltas and Plains” or, as far as I can see, in Abba and Bjarnason’s new and intriguing hypertext, Writing In The Age Of The Web. We’ve been writing hypertext for a generation and this simple matter of craft seems never to have been codified.

What else are we missing?

Well, there’s this: Iain Pears has written a hypertext fiction, reviewed here by the redoubtable Em Short.

And Stacey Mason, the Eugene Cota-Robles Fellow at UC Santa Cruz, responds to my earlier suggestion that we sometimes want to Let Go Of The Line with an intriguing case for Allusive Games.