Most of the tech press acts as if the surface design of gadgets is what that matters. Sometimes, they’re right. Most of the time, design lies deeper.

Lots of programming pundits right now will tell you that simplicity is what matters. Or testing. Sometimes, they’re right. A lot of the time, design lies deeper

The Problem

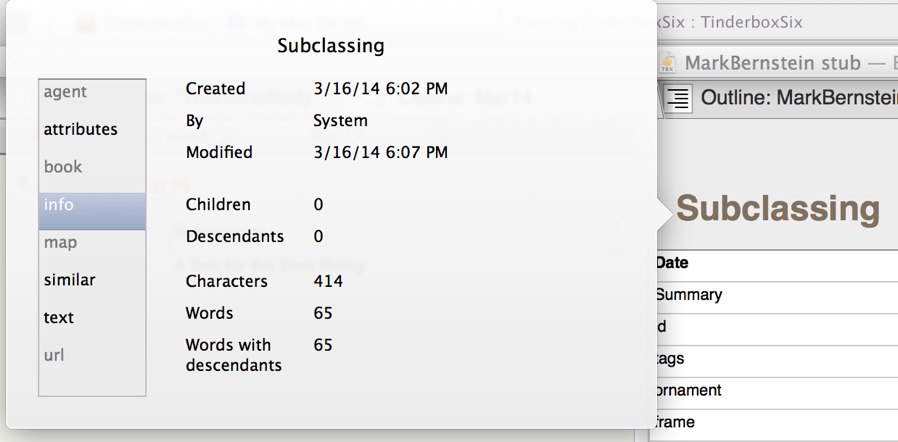

In a Tinderbox Six outline, pressing up-arrow moves the selection up, and pressing down-arrow moves the selection down. In a long, long outline, press and hold an arrow key. You might scroll through a page or two of notes and then, suddenly, stall. Now when it ought to be scrolling, Tinderbox would beep at you.

Clues

You always scroll through all the currently-visible notes, and then some more notes, before stalling; you never seem to stall immediately. ❧ There’s nothing special about the note on which you stall. ❧ Things are worse when you press and hold the arrow keys. Moving more deliberately, one click at a time, you’re less likely to stall.

Note that all these hints can be explained away by saying, “It’s unlikely that you’ll stall on any given note.” That turns out not to be the explanation, but that is the simplest explanation and Occam is often a terrific companion for the software detective.

Undercover

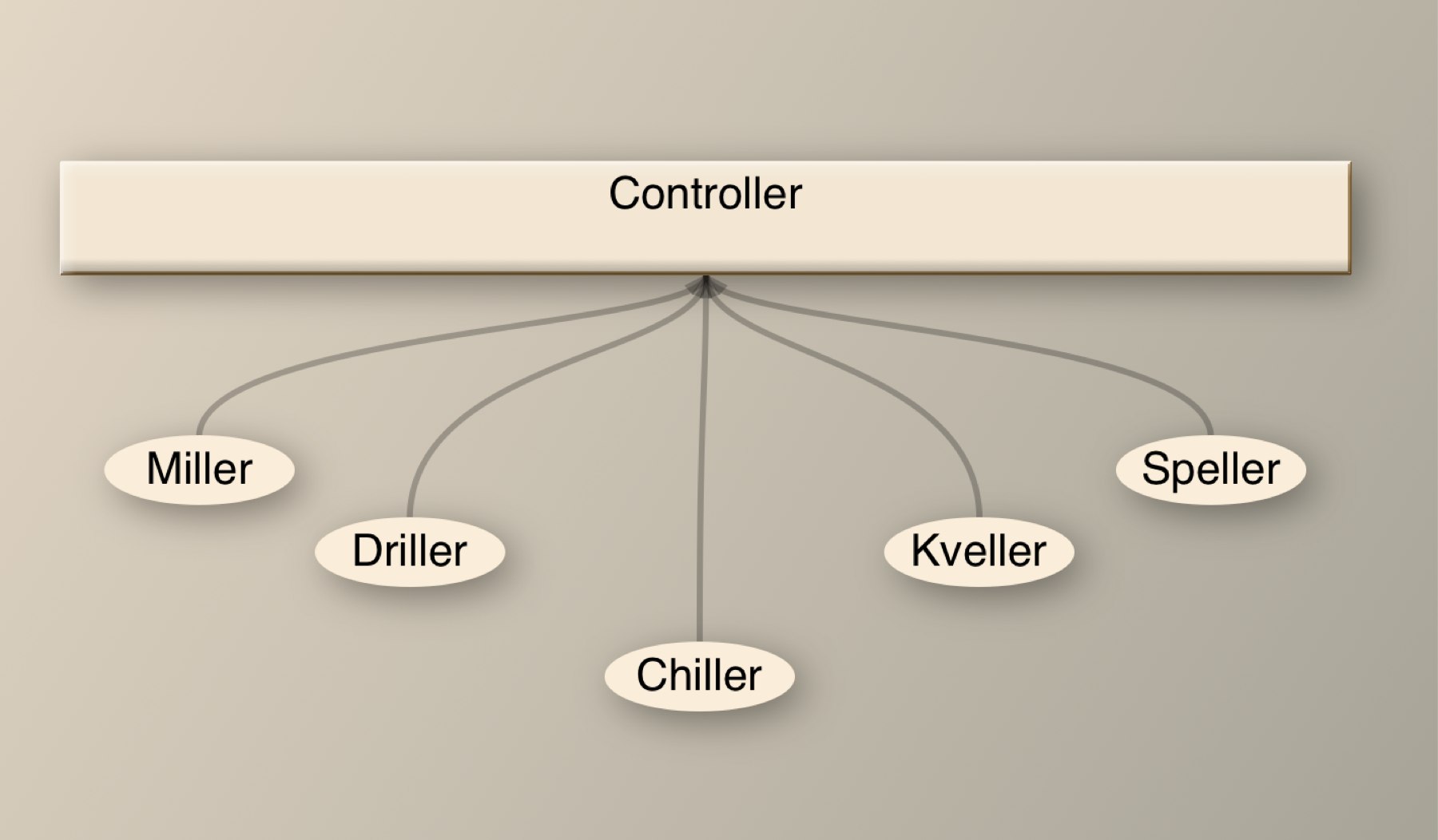

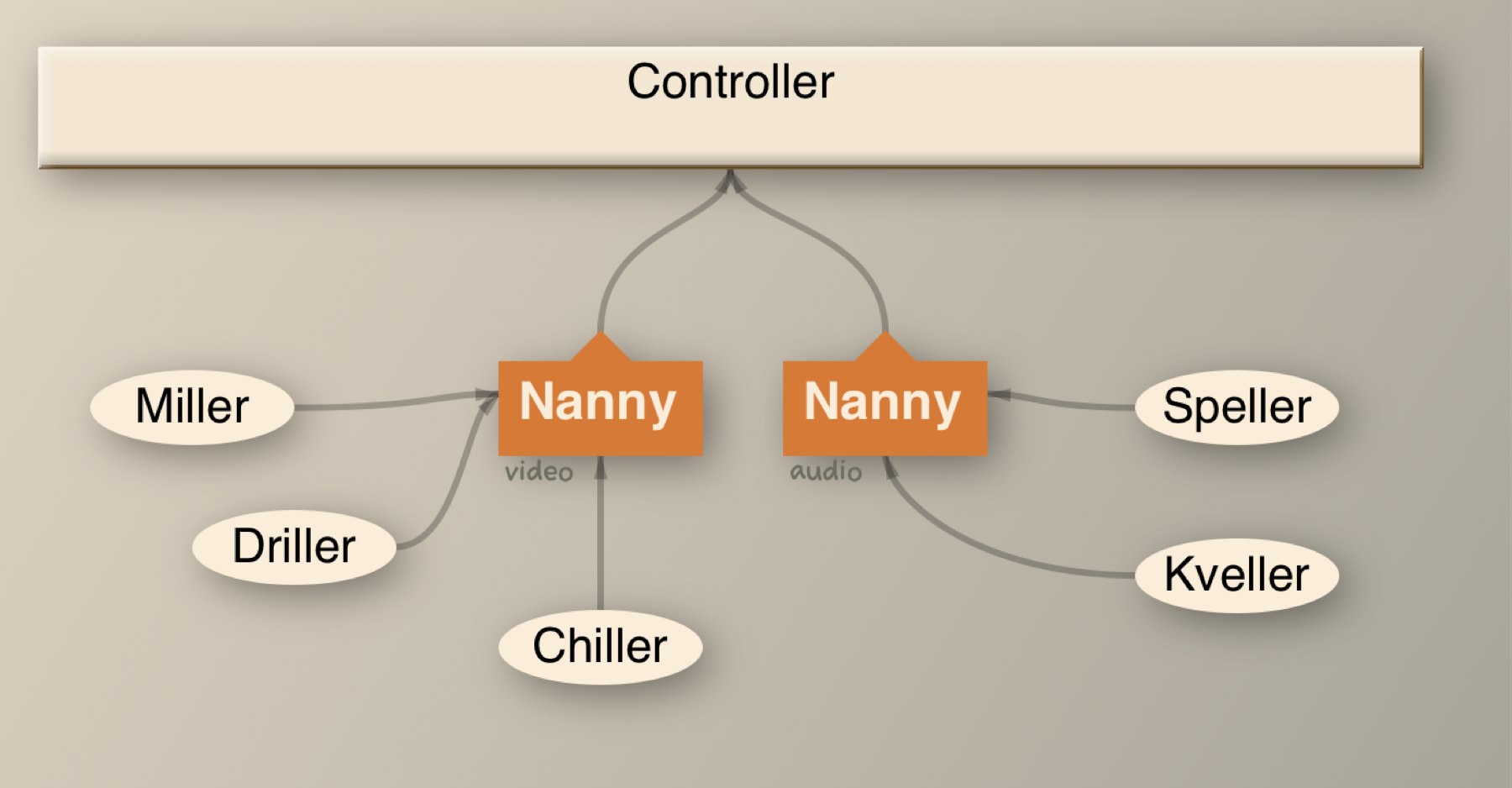

In an outline, each note has a MapItemView that represents the note on screen. Inside a MapItemView, we have a text field for the name of the note, and some other subviews. When we press the arrow key, we do several things:

- figure out which note is the next or previous note.

- select it, giving it first responsibility for handling events

- if that note is off screen, scroll until it is visible.

This is pretty simple, and it’s hard to see how you could make it simpler and still do what needs to be done.

In fact, it’s really too simple, because a big outline will have hundreds of notes, maybe thousands of notes, but only a few dozen notes are going to be visible at any one time. Views are big, complicated things that take lots of work and lots of memory, and the views that are outside the scroll area aren’t doing us any good. So, we add some logic:

- if the note is offscreen, put its view into the recycling pool

- if the note is onscreen…

- if it has no view, get one for it (preferably a recycled view)

- if it’s changed, ask the system to redraw it when convenient

That’s simple, too. When do we need to do this? Well, obviously, we need this when we scroll. And when we press up-arrow or down-arrow, we’d better be sure that the note has a view before we select it and put it in charge of event handling.

Crime

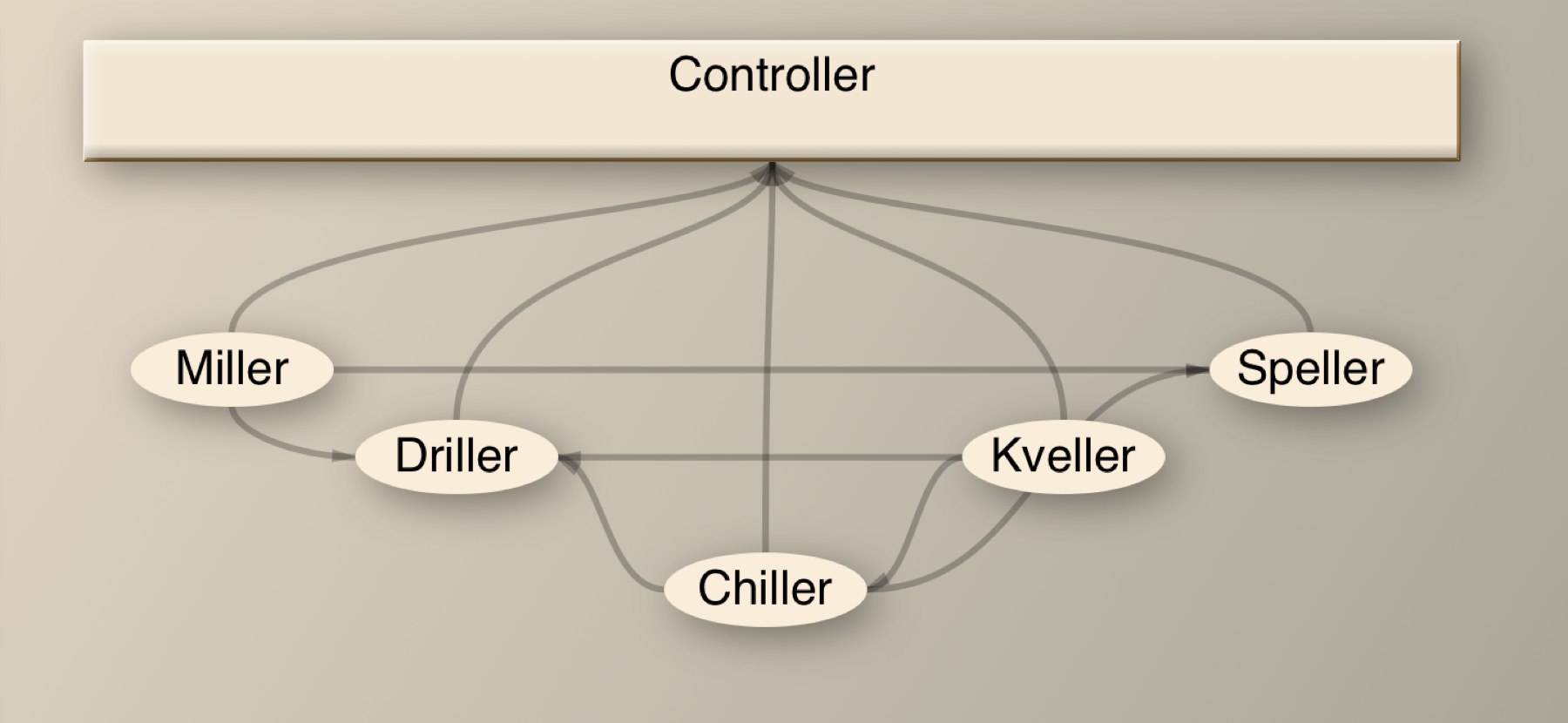

And there’s our answer! At the bottom of the screen, we press down-arrow several times in a row, very quickly. The note we’ve now selected is, say, five notes below the bottom. It’s now in charge. And we press again, so it’s going to hand off to the next note.

BUT… scrolling is animated — jt plays out over time, on its own schedule. So now, perhaps, we scroll the screen a bit. And maybe we look around for any off-screen views we can recycle. We’re pressing down-arrow, so a bunch of views have scrolled off the top of the screen. Recycle them!

Oh — and there are some views beneath the bottom of the screen, too – because we’ve pressed the key so quickly. They’re offscreen. Recycle those, too!

And so the view that’s responsible for handling events goes into the recycling pool. Sure, before the note gets to the edge of the screen, we’ll make it a new view. But that view won’t be handling events. And the old view won’t be, either, because we’ve removed it from its window and that takes it off duty. So no one handles events, and we start beeping.

Investigator’s Report

I began with the usual suspects and routine probing, but got nowhere. This persisted through several attempts, concentrating on finding attempts to set the keyboard focus. Ultimately, every Tinderbox method that explicitly set the keyboard focus was examined, but none appeared to by setting it incorrectly.

Once I knew this investigation was at least a bear and possibly an epic, I concluded that the actual crime had to be that some unknown rogue object was covertly stealing the keyboard focus. To catch the thief, I eventually built all sorts of monitors, ultimately subclassing NSWindow so I could intercept every call to makeFirstResponder:, only to find that no one was stealing the keyboard focus. If no one was stealing the focus, why was firstResponder a note one minute and nil the next? Oh: someone is stealing the view, and that view was holding the keyboard focus. To steal the Torkington Tiara, they abducted Lady Torkington.

Verdict

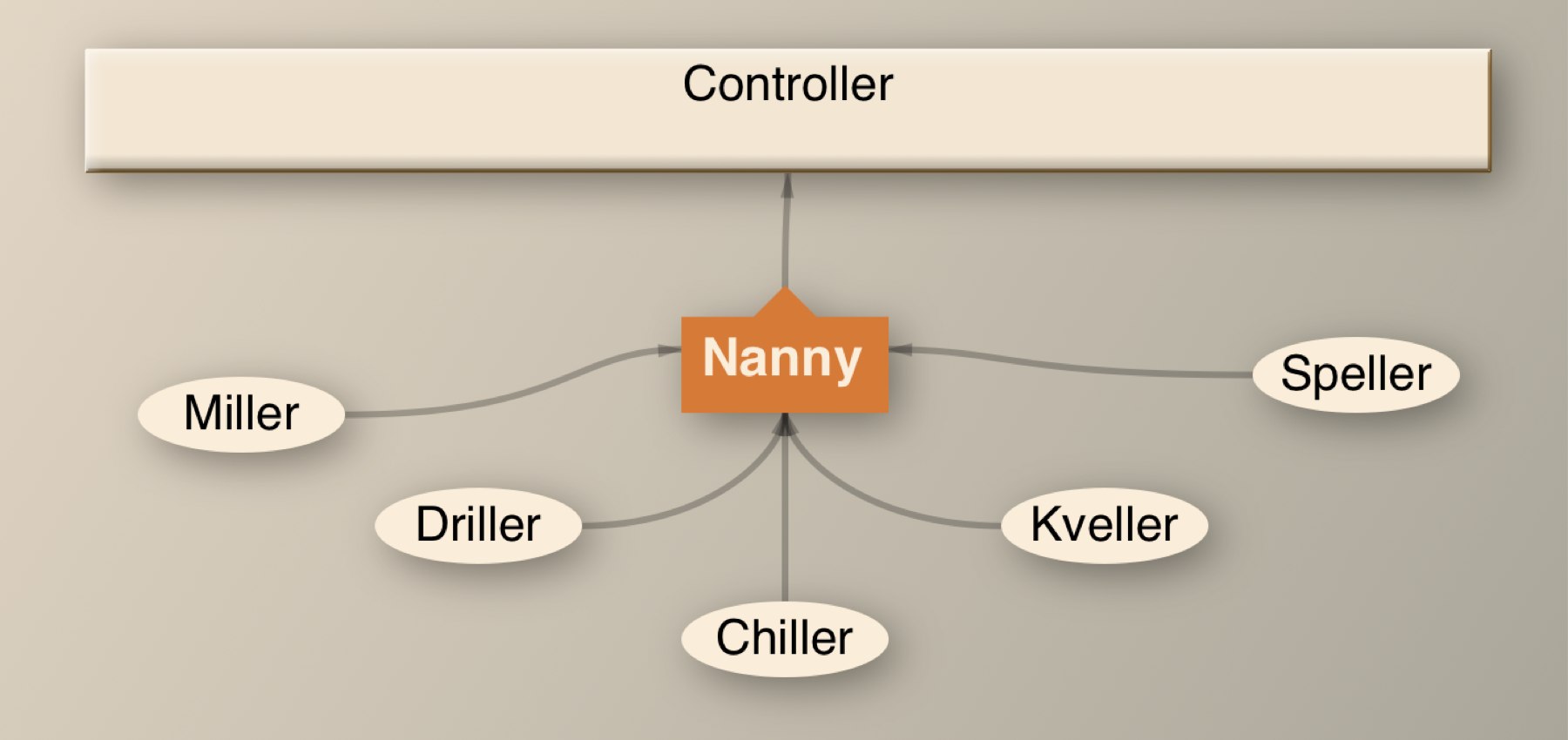

Just don’t recycle a note that’s selected. Wait until it’s not selected, even if it’s offscreen.

Punishment

On the surface, this was a tiny UI glitch, one that’s barely an inconvenience. In practice, it might require an unnecessary mouse click for every 100-250 arrow key presses. Say a mouse click takes 3 seconds, and the average user makes $100,000/year. That’s about a nickel per click. But a lot of that scrolling isn’t really productive anyway: lots of scrolling is actually a displacement activity, something people do while they’re thinking or worrying or waiting to get off the phone. So making that scrolling a little slower or less fun isn’t good, but it’s not really costing anyone any money. How many unnecessary mouse clicks do we need to save to justify the twenty or thirty hours it took to solve this?

Of course, solving the crime is a good thing in itself. Now that it’s fixed, we understand the system more completely. The user experience is now more solid, and that reassures everyone. A byproduct of all that debugging is some refactoring that clarifies the code.

That wasn’t the case ten years ago, by the way: before refactoring, long debugging adventures tended to make the code worse, not better. You’d add instrumentation and sensors and loggers, you’d try experiments, and inevitably some of that scar tissue made its way into the final product.

The Official Party Line, of course, calls for infinite attention and polish and emphasizes the importance of a pristine user experience. This makes some sense on its own, and also because relentlessly solving this problem revealed a small but systematic problem in recycling. We have lots of separate processors performing their own tasks, we have animations going on all over the place, and any of these might at any moment need to make sure that some note it’s working on has a view – any might recycle our offscreen view and foul up event handling.

But it’s not always that simple. Lots of small UI glitches turn out to be small, esoteric bugs that don’t matter. Lots of outright crashes turn out to be small, esoteric bugs that will matter only to the four of people who will ever experience them. This particular bug had a one-line fix, but that one line probably cost a few thousand dollars. For a few thousand dollars, you might be willing to put up with some visual artifacts.

Policy Implications

Would better testing have caught this? Probably not, because the critical factor here is that scrolling is animated and asynchronous. Asynchronous tests are difficult to write, slow to run, and therefore costly. There was no particular reason to expect this Spanish Inquisition.

Would better debugging practice have solved this faster? I’m not sure, even in hindsight. The firstResponder was correct here and wrong there; the natural assumption was to ask “who is changing the first responder?”

Would better design have prevented this? I’m not wild about the view recycling, which smells of premature optimization. But Apple does it conspicuously in NSTableView, which suggests (a) it’s desirable and (b) the rest of the system expects it. Tinderbox users build much larger documents than you’d expect, and that means we could wind up with a ton of views and that will bog down your computer. But we’re not building this for your computer: we’re also building this for your computer in 2024. And remember, Moore’s Law says that your 2024 computer is going to have 64GB of memory, 4TB of hard drive, and 64 cores.

At one of the first computer science conferences I attended, someone asked markup language pioneer Brian Reid about the prospects for WYSIWYG editors. Reid pointed out that paragraph formatting was just too CPU-intensive, observing that it could “bring a dedicated 370 to its knees.” Now, of course, we do that on our pocket phones.

Avoiding premature optimization sometimes means, “keep the software slow and simple, and let the computers catch up.”

I think fixing this was right, but it’s a near-run thing. We never talk about the bugs we should let be.