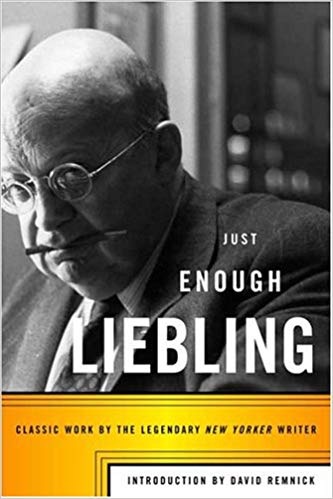

by A. J. Liebling

A. J. Liebling wrote wonderful columns about food for The New Yorker in a time when food writing was seldom considered suitable for anything but the women’s pages. His account of being an impoverished art student in interwar Paris and choosing between good food and good wine is memorable, and is also a modern morality.