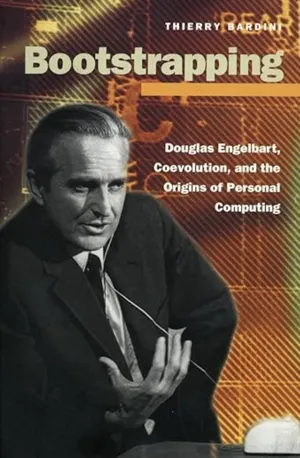

by Thierry Bardini

A surprising treatment of Engelbart’s crucial and influential (though short-lived) effort to augment human intelligence. Engelbart’s group really got started in the mid-60s, and broke apart in the 70s. Bardini is exceptional in trying to understand the collapse as well as the glory days. A lot of evidence is drawn from a roman a clef, which is discomforting, but it is reinforced by the group’s copious electronic records.

A key lesson is that Engelbart was not alarmed by the prospect that this line of research might bring about the apocalypse of the singularity. Indeed, Engelbart welcomed that: if there were to be a singularity, why not face it with better intellectual tools? Bardini makes this fairly clear, where in several conversations he and I had at various conferences, Doug could not.