The Kolkata Lecture 3: The Wealth Of Books

It’s sometimes thought that computers are merely tools, like automobiles or ovens: useful for getting work done cheaply, but fundamentally uninteresting or chiefly engaged with manipulating lots of numbers.

Or, worse, people think such tools are inherently menial, used of necessity by businesspeople and service workers but ill-suited to the scholar’s hand. This is no more true of the tools of computing than it is of the tools of history, of painting, of chemistry, of verse.

Das Endziel aller bildnerischen Tätigkeit ist der Bau! The ultimate goal of all creative activity is the building, and the work of the bricklayer is no less a part of that than the work of the cabinet-maker, the sculptor, the engineer.

Nicolai Troshinsky just twittered to me that, “I know a lot of artists and coders and I assure you, they are different kind of people.” But which kind am I? I suppose poets and painters are different kinds of people, on the whole, but which was Rossetti? Which kind was Rabindrath Tagore? Novelists and bureaucrats are different kinds of people; which was Trollope?

If you think that programmers and artists are different kinds of people, you will eventually start to think that one kind is better. And, if you start to think that they’re different kinds of people, you will excuse your own failings because you’re not that kind of person. And, when your work is not what it ought to be, you can blame the other guy.

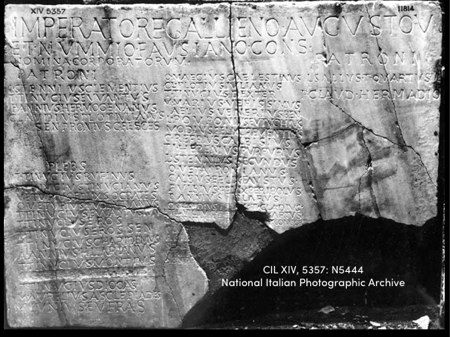

Today, computing may reasonably take its place among the arts and sciences. Or, if not, we may invite it to drop in after dinner. From the invention of computers, humanists have been using computers to do their work. Digital Humanities seem new, but already their influence on the intellectual landscape is profound.

In the talk, I show a “victory lap” of landmarks in the digital humanities, from Father Busa to Perseus and TEI and The Victorian Web. But I start in an unexpected place: a charming fantasy novel that won this year’s Hugo and Nebula Awards. It’s the story of a little Welsh girl. Her twin sister recently died in a terrible accident, she herself has been crippled, her mother is institutionalized. She is being sent off to boarding school. She already knows magic, but she finds solace in books. She reads all the science fiction in the school library. She scours the town shops. She cannot get nearly enough; her quest — familiar to many of us — is simply to find the books she wants to read.

This literary famine was long the natural condition of those who love books. And though it may not yet be over, digital delivery clearly shows us a path toward the end of this long drought. We do not think of this as a triumph of digital humanities, but of course that’s precisely what it is. I sit here in Kolkata, I push a button, and someone’s spare copy of Moretti’s Atlas Of The European Novel will be sent to my office.

Franco Moretti has made a number of contributions to our understanding of literary worlds, but none more than the crucial question of the rate of production. Old book worlds, and isolated ones, had only a few books which people studied and restudied. Time and again, book worlds transform themselves when there is, at length, plenty of new books to read, to discuss, from which to choose. The end of the book famine will have great consequence to the enterprise of the humanities