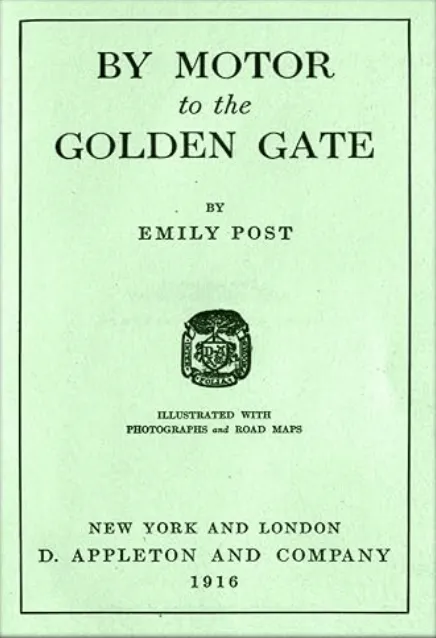

In 1915, an editor suggested to magazine feature writer Emily Post that she determine if it was, in fact, possible to drive in comfort from Manhattan to San Francisco. This book, which is very good indeed, describes that journey. Post had money (though her famous books on etiquette were still some years in the future) and had no particular interest in roughing it. Yet, not only did it prove possible: it turned out to be fun.

I’ve just returned from a 4,600-mile jaunt to Key West and back. For almost the entire route, you can easily see three separate eras of road technology through your window. Often, they run side by side. There is the multilane Interstate that bypasses everything and cuts through mountains. That often runs near the old Main Highway that runs between major cities and has rock cuts to reduce steep grades. Not far from that highway, you’ll find the road of the Emily Post era, running from the Main Street of this town over the the Main Street of its neighbor.

At one point, near the archaeological site at Etowah, GA, we took Old Old Alabama Road until it merged with Old Alabama Road, and then took that to Interstate 75.

Post discovered that, in 1915, American hotels were surprisingly good, and American roads were, top be charitable, variable. Regulations were a problem, too: entire states imposed arbitrary and unreasonable speed limits. The big problem, though, was that her magnificent European car had eight inches of clearance while most American cars had ten: that meant ruts were a real hazard.

Starting out.

August 11, 2024 (permalink)