Next is a fascinating Chicago restaurant that serves a single, fixed menu that changes every three months. You don’t make reservations; you buy tickets. The current menu is titled “Tour of Thailand.” It’s full of fascinating ideas.

Next is owned by Grant Achatz and Nick Kokonas, the cerebral pair who created Alinea. A few years ago, I wrote a piece about one dish: Alinea: What the Pigeonneaux a la Saint-Clair are saying. Next is not pushing the same boundaries as Alinea, but there are lots of ideas in every course.

Street food: served on a table spread with fresh Thai newspapers. Roasted banana, a prawn cake, a tasty sweet shrimp, a piece of sausage, a steamed bun. All paired with a cocktail based on Batavia Arrack, guava, and mango. The roasted banana was particularly complex and unforgettable, but this is all nifty food. Asian street food is a problem: you don’t get it in the US, and eating on the street still feels chancy in the third world. There’s always Singapore, where the street food is immaculate, but this is a wonderful course.

Hot and sour broth, pork belly: familiar thom yum soup, redolent of chillis and lemongrass, kicked up a notch and garnished with an amazingly lean piece of pork belly. This seems a simple course, and you might think it’s more delicious just because they use better spices. I suspect there’s a lot going on here; I bet that pork belly, for example, is cooked sous vide for a very long time, and I bet there’s some quiet molecular wizardry going on with the broth, too. This is Achatz all over: do something really complex and don’t even mention it, letting the dish speak for itself. Paired with a cocktail of gin, chrysanthemum, lemongrass, and lychee.

Rice with condiments: just the usual – chili paste, salted duck egg, mango pickles, things like that. Except these didn’t come from a jar. I gather that Achatz doesn’t care for the duck egg, which was my favorite.

Catfish, caramel sauce. The advance story for Next promised a visit to 18th century Ayutthaya, the kingdom that preceded Thailand. This dish must be part of that vision, a memory of Thai cuisine before peppers arrived from the New World. Subtle and delicious. Paired superbly with a wine that goes by the unlikely moniker of Itsas Meni Hondarrabi Zuri, Bizkaiko Txakolina 2010.

Beef cheek curry. A big, hearty piece of beef cheek, beautifully braised, in a superb curry. Again, we’re taking familiar Thai neighborhood restaurant fare and making it better – not by using fancy ingredients like “Cadillac fajitas,” but by really thinking it through. What makes this dish is that you get one hearty piece of flavorful, perfectly braised and seasoned beef, rather than lots of little bits. Getting it right has got to be tricky, but it makes a hell of a dish. Paired with Half Acre Horizon Ale, custom-brewed for this dish with hibiscus, mangosteen and pomegranate. A terrific pairing – and I am not usually fond of fruit beers.

Clarification of watermelon, lemongrass. I wrote about this before. If you don’t pick up on the hint word “clarification”, you’d think this was just an unusual juice.

Dessert with corn, egg, licorice, service in a young coconut. A very elaborate composed dessert, worthy of Alinea for its play as well as the complex interaction of flavors and textures. This must be an absolute bear to make, but again you wouldn’t necessarily notice if you weren’t looking at all the different little products mixed together in your coconut. Journeyman in Somerville does desserts with lots of components, but they're on display; at Next, they’re casually tossed in your coconut (though it would not surprise me if the apparent casualness of the tossing is a carefully-cultivated illusion). Paired with Cusumano, Moscatto dello Zucco – a nicely acidic dessert wine.

Dragon fruit, rose water, and a rose. Perfectly delicious, served with a long stemmed rose to revive your sense of smell. Paired with Banks blended island rum, served straight. You wouldn't think raw spirit would work this late in the meal and paired with fruit, but it seems inevitable. I want a bottle, and I hardly ever drink rum.

Iced tea in plastic bags. Back to street food! Soft drinks in plastic bags are one of the details of being in Asia that you forget when you’re not. Nice bit of theater.

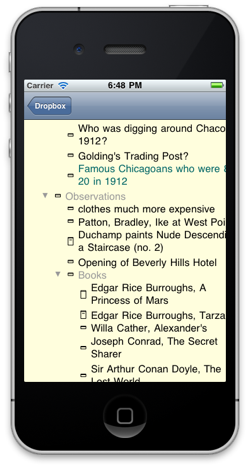

There’s lots of thinking here that I can see, and I’m sure I’m missing a lot. By selling tickets instead of taking reservations, for example, Next builds service into the charge and gets rid of tipping. Everyone is on salary, and servers and cooks both receive the service charge dividends. The menu itself is playing all sorts of inside games, moving from street food to elegant dining, from the reconstruction of ancient dishes to the deconstruction of everyday hot and sour soup to fresh construction of a wild composed dessert.

And in a couple of months, they’ll do something else!