At the start of a new research project, you often need to dig in and gather lots of readily-available information, not to accumulate facts but to map out the structure of the domain you want to master.

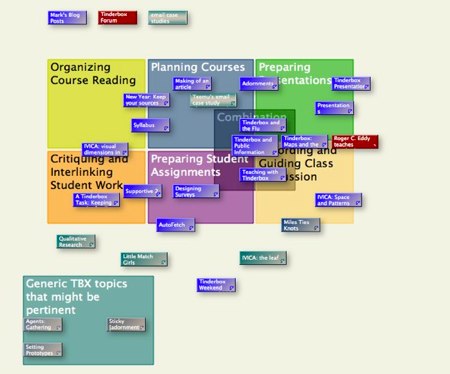

A recent Tinderbox Forum discussion on Tinderbox & Teaching led new Eastgater Stacey Mason to cast around for resources in Tinderbox and its role in education. She gathered information from Google, from Eastgate’s office library, from a new agent in this weblog.

The query is Text(tbx)&Text(teaching|presentation|assignment|syllab|classroom). The agent took a minute to write, and it's miles better than toying with a whole sequence of searches. And now that I’ve made the agent, it’s right there, updating itself with new notes (like this one). And I can share it with you.

Naturally, Stacey kept notes in Tinderbox.

Notice the interesting way she uses adornments (including overlapping adornments) to organize the map. It’s easy to add notes, and easy to move them as our understanding changes. Adding a new category takes seconds; redefining an old category and redistributing its notes is just as fast. Unlike outliners and mind-maps and tag buckets, the tool doesn’t tempt you to retain your original organization by making big changes tedious and difficult. It’s easy to split categories, or to have notes that bridge areas, or to remind yourself that some categories might be provisional, flawed, or unrelated.

From New South Wales, the story of a very young student who handed in her homework, captioned “When I grow up I want to be like mummy!” Unfortunately, the student learned that images can be read in different ways, requiring her mummy to send a clarifying note to the teacher beginning:

Dear Mrs. Jackson,

I wish to clarify that I am not now, nor have I ever been, an exotic dancer.

Diane Greco remembers adventures in waitressing and that former American classic, "Steak oh poyvree!"

Snap decisions are everything in restaurant service. That night, I really didn't want anyone to be mean to me. I had just escaped a rotten argument with my mother, who'd interrupted my reading of Stanley Cavell's latest in order to harangue me about the nerve I'd shown in dropping to a size four that summer. (I'd been on a steady diet of coffee and crusts leftover from bread baskets at work, because I was too cheap to shell out for a real meal at the Cafe where employees got only a fifty percent discount.)

One evening back in Delaware, during the worst of DuPont, I got out my copy of Joy and made oyster stew. It was inedible. We had to go out for a burger. These things happen sometimes.

But not so much; after all, if you start with decent ingredients, good food is, well, good food. You can only mess it up so far. “Oyster stew” became proverbial, but it’s pretty rare.

If you cook like I do, you never know exactly how things will turn out. That’s why they play the games. On any given Saturday…

- gougeres

- ginger carrot soup, with cilantro and creme fraiche; roasted garlic and rosemary bread (sauvingnon blanc)

- duck confit, potato and fennel gratin (cotes du ventoux)

- slow-roasted shoulder of lamb with rosemary, anchovy, lemon zest, farro, spinach salad

- pecan pie (bourbon, coffee, Heath bars), whipped cream (port)

This time out, lots of things went wrong. I got into the weeds and had to jettison the mignardises. At the other end of the meal, the gougeres were just a bit underdone. The confit didn’t crisp as well as I would have liked. Farro is a new dish for me, a nice way to use the fresh chicken-duck stock I’d just made. It went fine with the lamb, but “serves 4” was meant for another context, and I’ve got leftovers for a small army.

The freezer was getting a bit filled with poultry bones and so I made a batch of fresh chicken/duck stock for the soup. It’s a good thing I did, because farro has an insatiable appetite for stock.

The slow-roasted lamb was a bit of a mess, but this wasn’t Clotilde’s fault. At the butcher, there were only boneless shoulder roasts, and I realized too late that for Clotilde’s dish this isn’t a detail. The bone isn't just there for a little extra flavor; it's also supplying more fat and connective tissue that the slow roasting cooks to moisten the meat and improve the texture. Without the bone, the lamb was just too dry.

But it was lots of fun anyway, and I won’t need to eat anytime soon.

People worry endlessly about preservation of electronic artwork. They worry so much that sometimes people don’t make the art, fearing their progeny might find it inconvenient to view.

Of course, the progeny might be busy. They might by unappreciative. They might have lousy taste. To hell with them.

But a correspondent happened to remind me yesterday of a girl I knew in high school, a lovely girl who killed herself and of whom I have always tried to think (though I did not know her well) from time to time. She deserves that, at least. She lived and died long before the Web, and people didn’t write books about her, or even newspaper stories. There's no Facebook page, no twitstream, no blog.

Hypertext links are about memory. I try to remember winter...

The Giants’ Tim Lincecum is currently only 20 strikeouts behind the team’s all-time leader for strikeouts in a season.

Just for fun, I pointed this out to my erudite fantasy baseball league. Who is the leader? It’s none other than Christy Mathewson, 1903. Big Six, Matty. “M is for Matty/Who carried a charm/In the form of an extra brain in his arm.” That’s a lot of baseball under the bridge.

One guy, a physicist working in England, suggested Juan Marichal, remembering his high leg kick and legendary intensity. It was, he recalled, a thing of abject beauty.

“Abject Beauty” would make a great book title. It could, for example, serve for a baseball book: “Abject Beauty: a history of the Chicago Cubs”. Or, a biography: Octavia: Abject Beauty. True crime. You could do a lot with it.

Fresh New Day: an exciting manifesto and gorgeous Web project from New Zealanders Marica Sevelj and Lynsey Gedye

Stacey is a free and ultra-simple content server – a bare-bones CMS – that uses flat files and folders. It’s intended chiefly for design portfolios, but could be adapted to a variety of purposes for small to mid-sized web sites.

I can see interesting opportunities to generate Stacey sites with Tinderbox.

by Colin Cotterill

This interesting and sensitive mystery about Laos deploys an arsenal of fine writing to explore a strange and complex place and time. The Laotian monarchy has ended, the revolution has suddenly come to pass, and aged Dr. Siri is now the national coroner. The book is written as a series of tableaux — nearly, but not quite, independent short stories. The shifting points of view, the magic realism, the shifting of points of view and ambiguity of motivation, recall a quieter John Irving, and if the sun occasionally sets mauvely or the bear’s point-of-view seems a bit strained, Cotterill and Siri are each so competent that we know things will work out (more or less) in the end.

My fantasy baseball team, the Malden Mallards, has been playing in the Eddie Plank league for something like 15 years. Last year, we missed the wild card by 3 points out of 10,000 — the difference amounting to one additional inning of middle relief, or one base hit, over the course of a season.

This year has been neck and neck from the start. I had a toug day yesterday and so we’re now 15 points behind for the wild card and 90 points behind in the division. With two weeks to go, almost anything is possible and even likely.

In most years, the standings in our league change less than they do in real baseball — usually much less. I’ve never found a completely convincing explanation for this, but I think it’s because, in fantasy baseball, independent variables are more independent. Two batters who play on the same team are more likely to have a good or a bad day together than two batters who play on different teams.

It’s hard to know why these pennant races are so tight. If we were all playing optimal strategies, the spread might be expected to be small. But this small? The difference between teams is negligible: one missed start, two or three homers over 150 games.

What’s the problem with publishing? Why don’t people read anymore?

Look at me.

It’s Sunday morning. Linda’s asleep, it’s too soon to start the scones. I’m shopping for reading. I’ve got two urgent books queued up (history of weblogs and Israeli political fiction), but the horizon is empty and it’s probably time to look at the 27 books in my shopping cart and pick out what comes next.

I’ve wanted to read Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland since it came out, and wanted to read it even more since the Republican party made its 2008 journey from derangement to insanity. But, obviously, I ought to begin with his first book, Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus

. Last time I looked, that was out of print because the newer book’s success had cleaned out the warehouses. It’s back, now. Yay.

But wait! I’ve been meaning since April to check out The Landmark Herodotus

. I know exactly how long ago I added it to my shopping cart, because Amazon remembers for me.

Oh, and now that you mention it, the shopping cart still has Tony Barlow’s Sharp Teeth

, which sounds like your average everyday erotic werewolf book — have you seen how loaded Barnes and Noble’s back shelves are with these? — except that this one got terrific reviews. And it's in verse. Verse!

Yesterday, a Tinderbox user talked me into a reading a pair of new books about the New Deal . So the shopping cart isn’t getting any smaller. Just looking around at what else is in there. Mary Beard on Pompeii: great reviews, she’s been writing up a storm. Waverly Root on The Food Of France, which Druzinsky commends and which should lead to nutritious fall dinners, which Barry Goldwater seems unlikely to do. And a couple of dozen more.

And did I meantion I’ve got a stack of roughly 30 issues of the Times Literary Supplement that I want to scan for reading ideas?

Oh dear. Whenever I despair of a Tinderbox tire-kicker who simply can’t make up his or her mind to go ahead and buy the thing so they can get on with writing their book or solving their research problem or cracking their case, I think of the immense amount of work it takes to sell me on buying a lousy book.

An intriguing discussion of the impossibility of editing in the modern world, by editor Daniel Menaker.

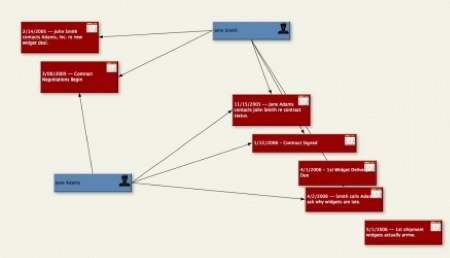

New at On Tinderbox and Litigation: A detailed look at using Tinderbox to represent the chronology of events that emerges in an investigation.

One important concept: it pays to use both lists of events and maps. Lists are compact, and Tinderbox outlines let you expand and collapse complex events with multiple components. But lists can be too compact, preventing you from grasping the intervals between events. Maps give you more freedom, but they take up more space, and sometimes maps can be simply too busy. You need both!

Wireframes offers a nice example of prioritized annotations for whiteboards, in which different colors of notes represent different priorities.

The notes here are attached to sketches of proposed Web sites. Yellow notes, for example, represent indispensable features, while orange notes are social features that might not be useful until the site has lots of traffic.

Seth Goden predicts the end of dumb desktop software. For example, take his iCal calendar:

If I try to schedule an appointment for 2 pm, it requires me to not only hit the 2, but also select pm. I have never once had a meeting at 2 am. Shouldn't it know that?

He proceeds from this to say that "The people who make desktop software are making themselves obsolete. When you start developing on the web, your default is to be smart, to interact and to be open (with other software and with your users)."

This is wrong.

First, the feature he wants is actually not so great — not when you schedule the 2am wakeup call for your 6am flight to Mumbai (where you have never been in your life) and find that your calendar changed the wakeup call to 2pm because it thought you wouldn't want to be disturbed. Besides, you never go to Mumbai; you must be catching the 6pm to Memphis.

Every day offers all sorts of unique circumstances. You know which matter because you know a lot. Your children don’t understand you, your rabbi doesn’t understand you, your dog doesn’t understand you. You want your calendar to understand you?

Second, machine learning is hard. The “smart” features Goden wants are based on inductive learning, but induction is full of tricks. Sure, your address book is full of phone numbers of people you haven’t called in ten years. Some of those people are dead. Some are people you’ll never need to call. But there’s also the phone number of the fellow who owes you one big favor, and someday (though that day may never come) you may need to call him and ask him for that favor. But if your address book considerately deleted it for you, you’re out of luck. (That Obama kid you knew in school? Well, you don’t need his cell phone number now that you’re grown up, do you!)

Remember the problem with Mom cleaning your room? Even your mother didn’t always know what was terrifically valuable to you and what was junk. Will your calendar will be better?

Third, Web development doesn’t make it easier. In fact, server-side developers are likely to be short on CPU, so lots of clever inductive strategies that are viable on the desktop won’t work in Web apps. Well, they’ll work in beta, and for the press briefing when the system has maybe ten users. Once things get built out? Fail whale.

Think I'm wrong? Just ask Sandy.

Of course, one advantage Web developers have had is that they’re new. It’s long been a maxim in software development that sometimes it pays to hire kids, because kids don’t always know what’s impossible, and sometimes find it easier to solve unsolvable problems than to learn why it can’t be done. But that has nothing to do with the Web.

Fourth, these features are expensive. That can work for core systems like the built-in calendar, and it’s fine for appliances like the iPhone, since development costs are amortized over zillions of users. But for software that everyone doesn’t use (or that everyone doesn’t use yet) the cost of getting the software to anticipate what you want can exceed the cost of asking you to show it what you want — often by orders of magnitude. This is the 37 Signals lesson: you don’t always need to be smart if you’re simple and fast and people understand what you do.

Note to marketers: software is not always the same as soap and cereal. Sometimes you can sell sizzle in software, but it’s got to work well at a good price. That’s engineering. Imaginary mystical Web goodness isn’t engineering, it’s wishing for magic.

Susan Gibb (whose “Blueberries” is worth a look) is reading Reading Hypertext. Perhaps you should, too.

It’s the season for school supplies – even for those of us who are far from school. Wireframes covers our urge to go buy a big box of crayons, markers, or colored pencils. And Veerle has a lovely piece on Moleskine sketching.

Eastgate has some nifty new Ciak journals with nice leather covers. $18 or $21, depending on size.

Susan Gibb has been looking at reading logs of her new hypertext story, Blueberries. And she’s worried about breaking her pact with the reader.

If you promise sex, you’d better not lead someone into dinner at Grandma’s. All trails must be interesting; just as in straight linear story, each sentence, each writing space, must entice.

But leading the reader to an unexpected dinner at Grandma’s is exactly what writers do. Mary-kim Arnold seems to be promising sex in “Lust”

this summer night

sweet and heavy,

he come to her.

But if you read “Lust” to look for the racy bits, you’re going to have a long and vexing reading.

Of course, all sorts of stories fail to deliver precisely what they promise. Take our old favorite “Little Red Riding Hood”, which we expect to lead to a nice meal at grandma’s. Instead, our heroine goes to bed with a most unsuitable fellow.

You never can tell. Which is why we like to hear the stories. On any given Sunday...

Nina Siegel revisits the best seller lists of the 20th century to ask, “Are today’s best-seller’s worse?” Are popular books more ephemeral, and are good books less likely to be best-sellers?

This goes to the heart of the grand literary argument of the generation. Jonathan Franzen and Ben Marcus have been debating , chiefly in the pages of Harper’s, the value of experimental and realistic fiction.

Franzen, for his part, worries in a Harper’s piece that was once titled, “Perchance to Dream,” and then reissued in his book, How to Be Alone, as “Why Bother,” that the social novel no longer has a place in literary culture because it can’t possibly expect to deliver to readers what other forms culture — from television news to the Internet or even extreme sports – already provide to mass audiences. Ben Marcus, in a piece in [October 2005] Harper’s magazine, “Why Experimental Fiction Threatens to Destroy Publishing, Jonathan Franzen, and Life as We Know It,” argues that Franzen shouldn’t do so much hand-wringing over the question of literature’s popularity, or the fame of great contemporary authors as compared to that of movie stars or sports heroes. He, instead, writes that because literature is an art form, it is, like all other art forms, dependent upon experimentation and innovation for its very survival.

Is there a good annotated bibliography of this debate? Anyone want to throw one together? Email me.

Gus Mueller has released version 2.0 of Acorn, his lightweight image editor.

The new version requires 10.6 – a gutsy move, but perhaps this makes sense since image operations can require prodigious amounts of memory and CPU, and Snow Leopard introduces new tools for getting more performance and addressing more memory.

If you read the current business press — especially in print, but also on the Web — you can’t help but notice that CEO’s of winning firms are brilliant (and handsome), while the leaders of losing firms are incredible dolts — pursuing obviously-doomed strategies, saying dumb things, and lacking the personal qualities that distinguish winners.

John Gruber often breaks the mold by actually showing a tactical mistake and identifying what was wrong. Today, Gruber calls out Sprint’s Dan Hesse for a poorly-thought-out interview. Charlie Rose asked Hesse whether the Palm Pre was "making a dent into the iPhone market", and Hesse answered that the Pre is doing well but that “the Apple brand and that device have done so well, it’s almost not… it’s like comparing someone to Michael Jordan.”

In other words, what Hesse tried to do was lower expectations, because for the business press it often matters as much whether you beat expectations as whether you actually, like, succeed. Gruber argues that this was a blunder:

This is one of the worst answers he could have given. Even just plain “No” would have been better than comparing the iPhone to Jordan, which suggests that Hesse doesn’t believe they can compete. He could have simply said that the iPhone has a two-year head start, and Sprint is happy with how the Pre is doing three months in.

Gruber’s right, though it might have been even more useful to acknowledge what Hesse was trying to do. (The same thing applies to sports. It’s pretty easy to see that the quarterback just threw another easy interception, but it’s much more interesting to explain what he thought he was doing than to harp on what a lousy throw he made.)

This is also the sort of mistake that seems consequential in the business press, but probably is not. If you read the naval history of World War II, you’ll be struck by a curious anomaly. Before August 1942, the allied navies kept making lots of silly blunders. Flammable paint is left on deck, people have the wrong equipment, watchstanders fall asleep at critical moments, the new model of torpedo doesn’t actually work. By late 1942, the allied navy is getting better and suddenly it’s Japanese seamen who fall asleep, foul up signals, run out of supplies, or steer the wrong way.

It’s almost as if the Allies started out with a virus, and suddenly they got better and the Japanese caught it.

People tend to think this was training: the US Navy got better, the Japanese got worse. In reality, though, it’s selective focus: mistakes matter (and are noticed) when they are costly. In 1941 and 1942, the Allies lost a lot, and naturally wanted to know why. By 1943, the Allies were winning. Everyone has a hand in a victory, and the mistakes — the missed signals, the cans of paint left of deck — are soon forgotten.

Update: This article has been massively retweeted. Thanks, all! Please do follow me on Twitter.

For breakfast, I made hot currant scones.

These are ridiculously easy; you take 2c (300g) flour, 2.5T baking powder, 1/3c sugar, a bit of salt, and a couple of handfuls of currants. Mix them with 1.5c (350g) cream. Knead to mix, hand-shape to an approximately round cake, brush with some melted butter and sprinkle with sugar. Divide the round cake into eight segments, put them on a cookie sheet. Pop them into a 400°F over for 17 minutes and you're done.

They take about the same time as omelets and pancakes and popovers. They’re tasty. And you get leftovers for tomorrow’s breakfast, too.

At Brand Savant, Tom Webster explores how Tinderbox can be valuable for designing questionnaires and surveys. It’s surprisingly complicated:

Survey questionnaires are not like other writing projects, however, in that they are, in a sense, 'programs.; Questions often depend upon the answers to previous questions, and some questions may or may not be skipped depending on prior responses. If you move a question towards the beginning of a survey that depends upon a response to another question, you need to be able to see what that dependency is so that you don’t 'break' the survey and can move the related questions correspondingly. You also need to check the logic of a survey instrument to be sure that you aren’t skipping persons on a given question that should actually get the question, and that you aren’t assuming ‘facts not in evidence’ by asking a question before establishing a critical bit of information.

Webster singles out Tinderbox for its versatility in moving between spatial hypertext maps and hierarchical charts and outlines.

With survey research tools increasingly becoming platform independent, there are lots of possibilities for Mac users in the field, and I highly recommend Tinderbox for a variety of research purposes. It can be complex, but doesn’t need to be, really–I just open it up and dump text in with the default settings and then worry about order and presentation later. With an outliner I am constricted to a hierarchical view, but with a mind-mapper, I lose the logical order that a survey instrument eventually needs to have. With Tinderbox I can shift from chaos to order, depending on the thinking mode I need to utilize, and the tool shifts with me.

Derik Badman’s Salmacis and Hermaphroditus is a hypercomic, designed with Tinderbox.

Instead of a single linear path through the chapter, you must click on panels to advance the page. Each framed panel is also a link that will take you to a different page.

From Joe Davis, an interesting stretchtext titled Telescopic Text. Thanks, Eric Scheid.

Glen Lipska asks which is more important: fun, or ease of learning? He argues that “most software developers get this exactly wrong.”

Most software developers and usability experts (shocker) focus on the easy part, rather than on the software being fun to use after they learn it. I have been trying to value the opposite priorities. Of course, I am not trying to make something hard to use. Rather, I am focusing on making sure the thing is fun to use. I still apply tons of usability techniques and make sure to include all the big UI five for the user.

Ed Blachman pointed this one out to me, drawing the connection to my NeoVictorian revival. And he’s got an even better point. He writes that we’re in a vicious cycle; “[enterprise software] developers decide we’re developing for drudges, so fun doesn’t matter; users are stuck with software that’s never any fun, so they regard using it as drudgework.” This is the textbook definition of alienation.

Fun is important. Results are even more important; getting the right answer, doing work that you could not do otherwise, beats fun and ease hands down. But, in the end, results are fun; they make you happy, they make customers happy, and along the way you’ll be rewarded with tokens that you can exchange for goods and services!

We talk far too much about first impressions and out of the box experiences, and far too little about letting people do things they couldn’t do before.

Andrew Sullivan says what I’ve been thinking all summer, with the Republicans packing pistols at political events while shouting nonsense:

I suspect the only way to unwind the ferocious cultural blowback from the election of a non-Southern non-white president is to let it blow itself out.

The fear, of course, is that it will blow itself out by assassinating him. I just hope the secret service knows what is being whipped up out there. And I hope that when the GOP leaders acquiesce to this insanity, they understand what Obama following Lincoln would do to this country - and the world.

by Zack Hample

A respected baseball writer Twittered that he learned a lot from this book. I think he was being more than somewhat generous, because I myself am a rather casual fan and I knew most of the things in his book by the time I was in sixth grade – and so did every other boy in the class. (This was the dark ages, when girls weren’t expected to know important stuff like batting averages until their late teens.)

OK: I did get two two things wrong. If a ball deflects off the pitching rubber and goes into the dugout, it’s a foul ball. I’ve never seen it happen, I'm not sure it could happen, but OK, when I took the 12-question foul-ball quiz, this one got me. And, yes, I’ve believed since sixth grade that errors did not count as a time at bat and this turns out not to be the case. Some sixth grader misinformed me. Don’t think I don’t remember who.

The book’s subtitle, “a professional fan’s guide for beginners, semi-experts, and deeply serious geeks” is wrong. This is what we, in sixth grade, would have called “a book for girls” — that is, a book for people who don’t really know much about baseball but might like to watch it. For that, it’s a fine book. (We will not mention at this point that the evening guy on WEEI dropped the ball on a question about the infield fly rule the other night.) I wouldn’t mind having the soccer version of this book, or the cricket edition. I once watched a Rugby final in Sydney, and it sure would have helped to have a pleasant and amiable read like this.

It’s a shame, though, because there’s a ton of interesting stuff about baseball that I’d like to know. Here are a few:

- What is the best way to score a game at home? In a modern radio booth, who scores the game? On paper? On computer?

- Do teams really differ in teaching fundamentals? How? People used to talk about the Orioles as being driven by fundamentals; true? What about scouting philosophies?

- Some teams have had historically bad runs: the Cubs, the Pirates, and the Orioles have all had a rough time in their own way. In the past, you could point to Cleveland after the Colavito trade, or the Phillies after the breakup. Why were each of these teams so bad? Was it just luck, or poor judgment, or a fundamental misunderstanding?

- Hample says that modern batters, following Ted Williams, do not deign to take advantage of the overshift. That’s not true: the modern overshift, as I understand it, was revived for David Ortiz, and he does try to go to the opposite field, or bunt. He generally fails, but it sure looks like he’s trying. Am I wrong?

- Hample says the last left-handed catcher was a Pirate in ’89; I could have sworn that the Red Sox used a southpaw emergency catcher more recently.

- Someday, a woman will play in the majors. What will her position be? (My bet is 2B, but you could make a case for C)

- OBS strikes me as a bastard statistic; you can’t add two ratios and expect the sum to mean much. What says the defense?

- What are the odds that a runner on first, no outs, will score? How about the expectation value for an inning with the bases loaded, 2 out?

- In the late 1980’s, Bill James started an analytic revolution. How has this changed the game? How has it failed to change the game? Where has it proven wrong?

- There are dozens of little things players do, because something that never happens might happen. Third basemen are supposed to back up the pitcher after a pickoff play. On a popup to short center with a man on first, who covers second in case the runner tags? A compendium of these little things would be nice to have.

- How exactly do options work? (In the next labor negotiation, should the union demand a way for players to get more options? Or should the owners?) Why do teams want to name players later?

- How do baseball fundamentals differ in other places? What strategic moves might you see in Korea or San Pedro de Macoris that you don’t see in the Bronx?

Jørgen Jørgenson wanted to make a nice little Saturday dinner with his wife. And what says dinner more than beef?

And, he figures, if you’re going to have steaks, why not wagyu beef?

And, since wagyu beef needs a sauce, why not make a stock with 4 or 5 lbs of beef bones, and reduce the whole batch with some onions, carrots, celery, and port wine, from a gallon or two to a cup 20ml — a tablespoon or two. Served with a 1997 Margaux.

Oops. Chemists don’t use deciliters and I slipped a decimal point. How embarrassing, though it does give me a chance to test Tinderbox new strikeout markup.

That's more ambitious than I’m feeling this weekend. So I’m keeping it simple: barabcoa made from sirloin plate, grilled sweet corn from Northampton, a little romaine salad from Linda, some fresh bread, a small chocolate cake from Meryl, and some lemon sables for lilly-gilding.

by M. K. Moulton

The American Nazi party is marching in Skokie, gathering steam and frightening the neighbors. When Gershon Levin, a pious survivor of the camps, is found dead by cyanide poisoning, the police call it suicide, his rabbi reluctantly agrees, but his friends and neighbors and his energetic Israeli brother Uri team up to figure out what really happened. Moulton believes the Nazis to be a real and specific threat, not mere sad kooks, and she makes the argument with force and conviction in this engaging mystery. I worry that this excuses Christianist Republicans who believe in the same things and pursue the same methods but use a new logo. The Republicans have better resources, more money, and their own television network. Just as worrying, the story is weighed at the outset by buckets of exposition reviewing the outlines of the Holocaust; I’d have said, “Everyone knows this,” but Moulton’s long career as a history teacher (I was once her student) doubtless gave her reason to conclude they do not.

by Stieg Larsson

Lisbeth Salander (The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo) returns in a superb mystery thriller. Among the best of the year, and deserves to be discussed among the best ever. Fascinating perspectives on Sweden, on the grievances and cruelties the human spirit can find even in socialist paradise, on the construction of a thriller without artificial peril and without buckets of firepower, and on the problem of a Watson with self-respect.

I've been reading, and enjoying, Dan Cederholm’s Handcrafted CSS

. But Cederholm — and everyone else — seem to me to be dancing around an unspoken but serious blunder in the way CSS is designed.

Perhaps the most natural way to choose the size of body type is to relate it to line length: a line should not be too long, or too short. If you’ve got plenty of space, you choose a larger typeface. If you’ve got to fit into a tight corner, you use smaller characters. Everyone knows this, but CSS won’t let you do it.

CSS lets you say, “This column runs half-way across the page”, and then adjusts the column size to the page size. But (as far as I can see) there’s no way to say, “I want to choose whatever text size gives me 45 ems per line.” And that’s the common case! Yes, you might also want a minimum-size (45 ems per line, but never smaller than 9pt) or even a maximum size. But most often, you want to specify font size in terms of line length, and this seems to be exactly what you cannot do.

Of secondary interest; nobody talks about this gap. Why not?