- aperos:

- pear and hazelnute madeleines (pear & hazelnut)

- cruidites with onion dip

- home-smoked swordfish rillettes

- wasabi peas

- lollipops on fire (bourbon sweet potato fritters, served on smoldering cinnamon sticks)

- alliterative salad: papaya salad with pickled peppadew peppers, stuffed with goat cheese

- duck burgers on home-made brioche rolls, celery root remoulade, apple chutney, aioli

- home-made corned beef on home-made rye

- parmesan custard, romaine, anchovy dressing, parmesan crisps

- Meryl’s intense chocolate tart

- lemon cayenne cookies

The lollipops were meant to adapt an Alinea idea to human scale. At Alinea, they make three gels – bourbon, sweet potato, and brown sugar – skewer them, and then dip them in tempura batter. The fritter is less refined, but it’s much easier. It’s surprisingly hard, though, to ignite cinnamon sticks.

The papaya salad was supposed to have persimmon, too. But I tasted the persimmon as I was slicing it, and decided that persimmon, while lovely, is not really fit for human consumption. The green papaya wasn’t green, either, but the spicy fish sauce dressing worked anyway.

At Electric Literature, Kristopher Jansma implores us to “Damn The Man, Save St.Mark’s," a New York bookstore once haunted by beats. He even-handedly deplores petitioners and protesters:

As The Awl points out, petitions are nice, but they do not pay the rent. If the 43,825 people who have currently signed the petition had also bought a nice new hardcover novel for $25.99, the St. Mark’s Bookshop would have no trouble paying its rent for the next 4 years.

The Awl’s Choire Sicha, unfortunately, is mistaken, and he’s taken Jansma for a ride. In the U.S., booksellers operate on a 40% markup, so the gross margin from these purchases would be $455,000. Merchant fees on credit cards will cost about $9000, and minimum-wage cashiers to simply handle the checkout are going to cost at least $9000.. The average hardcover weighs about 18oz, and shipping 49,000 pounds of books might cost you at least $30,000. Now we have $407,000. I’ll ignore taxes, heat, electricity, security, fixtures, stocking shelves, providing a selection of books, returning unsold books, or the fact that New York can be expensive.

The store’s current lease runs $20,000/month, which is $240,000/year. The windfall would not quite cover two year’s rent, and surely nowhere close to four.

None of this is arcane. The core mistake — forgetting that booksellers pay for the books they sell — is a simple fact of life. The Awl is small, but it’s got two reporters and a publisher. Electric Literature is a publisher, and probably knows that publishers get paid. Why doesn’t anyone catch these?

For recent piece in The Guardian, Alex Strick van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn used Tinderbox and Google Maps to analyze the effectiveness of US tactics in Afganistan. Wired reviews the technology.

Judy Malloy (its name was Penelope -- coming soon for iPad) interviews Stuart Moulthrop (Victory Garden):

The legend that is TINAC seems less like some intensely obscure indie band whose members are all now shepherds, and more like a college-town FM station that flourished for a year or two before the supremacy of News-And-Talk. By which I mean, there was really not much "there" to TINAC, except as a point of circulation and convergence through which some interesting projects happened to pass -- Michael's afternoon, Nancy's annotation software P.R.O.S.E., John's Uncle Buddy's Phantom Funhouse, Jay Bolter's Writing Space, Jane Yellowlees Douglas' End of Books, or Books without End, and my own early tinkerings. TINAC left the air long ago. The call letters are remembered only dimly, the DJs are all forgotten, but somewhere out there, doubtless on the Net, we'll always have the music.

“It could be exceptionally important to create a testing program for electronic literature,” Moulthrop suggests. “I am not kidding. I would give huge kudos to anyone willing to operate such a thing. We should write a grant. Or someone should. Anybody?”

A Day In The Life Of A Las Vegas Casino Helper: an exceptionally well-written series unfolding at eGullet.

The man in black walks to the lectern and begins. “Today’s reading is the second clause the the Dryden Minifesto.”

II) Any person.

Interaction manifests itself through recognition, sympathy, and witness as much as through impersonation, perception, and exploration. Apprehension of character is participatory design.

Apprehension of character: it it not sufficient that there be characters, that they populate the narrative. We must apprehend them. And we do not merely see what is written, what is placed before our eyes by the author; we conspire with the writer to create the character. Reading, we design characters.

Diane Greco once explained that, to make a character lovable, you need only take steps to ensure she has no interior life, and that everyone loves or wants to love her. The writer sets the table, and the reader supplies the meal.

This was true when Homer recalled the bitter anger of a proud subordinate, and it was still true when Will himself was Hamlet’s ghost. It is, indeed, participatory design; we don’t do it ourselves, we can’t choose anything, but we bring a lot to the table. The reader needs to work

; she always has.

Recognition, sympathy, witness: interaction. When we speak of interaction, we usually talk about mouse clicks and touches, commands, intentional gestures. Or we discuss the absence of interaction, the film unrolling, the world unraveling, or things unfolding as they should. But sympathy, too, is interaction. Sympathy is the door in the wall behind which lie the delights of new media, and its absence often leads to unhappy, hostile reading.

Here endeth the lesson.

Perhaps no recent writer has inspired richer reminiscence than has Pauline Kael. In The New Yorker, Nathan Heller equals the best of these with What She Said: the doings and undoings of Pauline Kael. 5000 words, and worth every one of them.

A lot of people now . . . dream of a lost moment when the opportunities were truly “hidden like Easter eggs,” when the paths were not yet mapped and overrun. How can we be expected to create properly, the thinking goes, without the tools of past success? How can we write without the old serious publications, make movies without risk-taking Hollywood producers, live without cheap urban housing, discover art without the underground, make a career without the circulation-desk jobs?

Kael’s great achievement was to fight this way of thinking, to persuade her readers that work is always done with the machinery at hand. It was, for her, a liberating insight. The last movie that Kael reviewed for The New Yorker, in 1991, was “L.A. Story,” a small Möbius strip of entertainment-biz insiderism nothing like the New Hollywood chefs d’oeuvre that had once thrilled her. Yet she loved it. In the last line of the piece, praising Sarah Jessica Parker as the ultimate Tinseltown child, it’s possible to see Kael wink twice. The first wink turns this closing statement into an epigraph for her career. The second alludes to the modern classics that she never lost touch with. The line that ended that review was “She keeps saying yes.”

A popup unconference on strange hypertexts and narrative play. The second international web art/science camp. A lot of fun.

Boston. November 19-20.

Join us.

Last week I cited the 1988 Dryden Minifesto, TINAC’s fascinating 1988 proposal for a new way to write. There’s a lot to be learned from TINAC – lessons we never quite assimilated, lessons we forgot, lessons we only half mastered.

The very first statement seems puzzling today:

I) No interruptions.

Reading should be a seamless and uninterrupted experience. Its choices proceed from the expression of possibilities as a narrative medium and depend upon the complicity of the reader in the creation of a narrative. Reading is design enacted.

We might object, for example, that hypertexts – including the wonderful work the TINAC people were doing – is full of interruptions, since it’s broken up into screens or lexias or pages and since, in a hypertext, you need to choose a link. On a more theoretical plane, “seamless and uninterrupted” sounds like Gardner’s “perfluent dream” of immersive fiction. But Gardner extols the perfluent dream to oppose metafiction, the self-reflective manner of postmodernism, and early TINAC work seems to abound in metafiction. What can this mean?

Puzzled, I asked the authors. Nancy Kaplan was under the weather (feel better!), but the rest wrote fascinating replies.

John McDaid answers that “When you click and zap somewhere, as an anthropologist, you are inclined to say, aha, interruption. But the emic experience of the reader as she traverses that link is one of flow. This was, to me, no different in kind from a cut in film. No one but theorists says that a film is discontinuous because we cut to a closeup.”

Michael Joyce recalls that “In writing afternoon I was obsessed with having it read seamlessly in the way books did and which Gardner was neither the first nor last (me too) to overvalue.” In afternoon, links are not underlined or blue or frames, and nearly every word yields to the click. “They all (with a few planned and significant exceptions) were links.” Joyce also calls attention to the concluding sentence,

Reading is design enacted.

“There,” he writes, “we truly were way ahead of the curve in setting a standard by which almost all current interfaces fall short, as well as our own.”

Stuart Moulthrop responded with a new manifesto, fragmenting the stricture against interruptions into a twelve step embrace. He recalls that, in 1988, he was anxious to move the reader’s focus from the command line back into the narrative. “I liked afternoon because it moved interaction cues (clickable words) into the narrative discourse, rather than interposing a command line.” He has since recanted; “Interruptions are just fine, thanks. So are in-your-face interfaces.” Stuart also recalls Nancy Kaplan’s insistence that it’s impossible to read immersively anyway, that you’re always arguing with the author. (Even “real life” isn’t as immersive as the holodeck: Job’s question is always with us.) Moulthrop also raises interesting questions about the status of the tablet, “made not revealed, one among all the Moores allowed by Law.”

Stuart’s seventh point is an important lesson for all who write about new media:

This is not about computers. It's about books. Books won't die, and the world will always welcome novels, backlit or otherwise. I've found that a tendency to attack anything that doesn't look like a book or a novel (or the sorts of novels one writes) appears in inverse proportion to belief in the previous sentence.

by Martin Cruz Smith

It’s been thirty years since we first met Arkady Renko in Gorky Park. History ended, Russia changed and then changed some more and somehow was it was still Russia. Arkady is still wildly unpopular with his fellow investigators and despised by his superiors, yet somehow he still has a job and, despite every incentive to go along and get along, somehow he figures out what happened to the prostitute someone found in a trailer behind Kazansky Station.

by Jennifer Egan

The opening chapters of The Invisible Circus are crafted with stunning density and a lyrical touch, as Egan effortlessly unfolds the complicated, multi-layered emotional life of a small San Francisco family with naturalness, concision, and without contriving a lot of distracting incident. Phoebe, the youngest child, is graduating from high school, and impulsively heads to Europe to follow the path that her wonderful older sister, Faith, took some years before. It’s the early 70s; Dad knew the Beats, Faith knew the ’60s, and Phoebe suspects she was born just a little too late, that she was too young when it happened and now the circus has folded its tents.

Before this MLA dustup attempts (and fails – these things never work) to erase years of hard-won knowledge and finely wrought electronic literature that was created before ELO, I’d like to remind everyone about TINAC, the crucial movement that represents the moment in the late 1980s when the literary embraced the digital, when the street found its use for things and the thing knew itself.

TINAC was an informal gathering or collective, including many of the first literary writers who were actively committed to discover new opportunities in new media. I wasn’t part of this, not until the very end. TINAC stood for “Textuality, Intertextuality, Narrative and Consciousness” (or, alternatively, “This Is Not A Conference”) and included (among others) J. Yellowlees Douglas, Michael Joyce, Nancy Kaplan, John McDaid, and Stuart Moulthrop.

Here is the Dryden Minifesto from TINAC, promulgated in 1988:

I) No interruptions.

Reading should be a seamless and uninterrupted experience. Its choices proceed from the expression of possibilities as a narrative medium and depend upon the complicity of the reader in the creation of a narrative. Reading is design enacted.

II) Any person.

Interaction manifests itself through recognition, sympathy, and witness as much as through impersonation, perception, and exploration. Apprehension of character is participatory design.

III) Every ending.

Closure has been described as the completion of self by the reader. It is, in this sense, design determined.

IV). A read-write revolution.

Interactive narratives are what is written, whether by reader or writer. Authorship is an invitation to active design.

This manifesto is still interesting and timely, more than twenty years later. Its language and its concerns are difficult but repay concentrated effort. They assume a broad view of electronic writing, not the narrow focus that the ELO faction imagines hypertext has. Where most people today are still wrestling with surface mechanics — multiple endings, page turning, video illustrations – TINAC was already moving beyond that surface into much deeper territory. There’s no hint here that they were thinking only of blue underlined text: that historical canard arose from a misunderstanding of Aarseth’s Cybertext. Before ELO spent a couple of hundred thousand dollars on “branding” e-Lit, almost every serious scholar and critic used “hypertext” or “hypermedia” to include all, or almost all, the kinds of media that Aarseth called cybertext and ELO calls e-Lit.

(There was an additional ten-point TINAC statement that included the famous three-link dictum. I can’t put my hands on it right now. Can you? Email me. )

I had assumed that Prof. Emerson’s sentence about Glazier’s book was a slip-up that somehow got past her and the MLA reviewers. Happens to me all the time; you’ll find plenty of typos right here. (Does MLA have reviewers? Surely someone in the field read that first sentence, at least. I know that MLA has different standards of evidence from Chemistry or Computer Science, but colleagues are supposed to save you from things like this.) Supposedly, we’re all working toward truth and understanding, and the sentence as written is at least prone to misunderstanding.

Alternatively, Emerson might be asserting the claim that Glazier’s Digital Poetics literally redefined electronic literature and represents a clean break with previous critical and artistic practices. This doesn’t happen often – some would say it doesn’t happen at all – but one might point to Ruskin on painting, Shaw/Wilde/Eliot on theater, or possibly The Beatles as precedents. But to my knowledge, no one has ever published this claim for Digital Poetics – not even the enthusiastic Sandy Baldwin. It is, moreover, primarily a book about poetry, and the concerns of "digital literature“ are usually conceived as extending to prose. I know the literature pretty well, and I’ve certainly never heard this sentiment before. (I have the greatest respect for Glazier, whose indefatigable work to provide a space for electronic poetry has been of indispensable service to the field.) If that’s the intent, you’ve got to make the argument.

I’d expected Emerson would simply clarify the sentence, but her rejoinder tries to argue that the ELO rebranding of of hypertext and new media as eLit was both significant and crucial: that it changed everything and so makes earlier scholarship worthless (or not worth mentioning). That’s a very interesting argument: it might, for example, explain some of the strange gaps in the organization’s directory of electronic literature. About fifteen months have passed since I observed that

The directory currently appears to list 159 works. Some hypertexts that aren’t listed include Greco’s Cyborg, Kolb’s Socrates in the Labyrinth and “Twin Media: Hypertext Under Pressure”, Falco’s Dream with Demons and “Charmin’ Cleary”, Mary-kim Arnold’s “Lust” and “kokura”, Michael Joyce’s Twilight, a symphony and “Twelve Blue” and “WOE”, Brian Thomas’s If Monks Had Macs, Richard Holeton’s Figurski at Findhorn on Acid, William Gibson’s Agrippa: The Book of the Dead, Adrienne Eisen’s Six Sex Scenes, Carolyn Guyer’s Quibbling and “Izme Pass” (with Martha Petry), Judy Malloy’s Uncle Roger and its name was Penelope and Forward Anywhere (with Cathy Marshall), Rick Pryll’s Lies, Nitin Sawhney’s HyperCafe, Deena Larsen’s Samplers, Jean-Pierre Balpe’s oeuvre, Loss Glazier’s oeuvre, and George P. Landow’s Victorian Web.

A few of these were added last August, but apparently not Cyborg, Socrates in the Labyrinth, “Twin Media”, “Charmin’ Cleary”, “kokura”, Twilight, “Twelve Blue”, “WOE”, If Monks Had Macs, Agrippa, “Six Sex Scenes”, Quibbling, “Izme Pass”, Lies, “HyperCafe”, Samplers, Balpe’s oeuvre, Glazier’s oeurve, and Victorian Web. There seem to be plenty of other notable absences. Off the top of my head: Ryman’s 253, Marc Saporta’s Composition 1, Robert Coover’s “Heart Suit”, Deena Larsen’s Marble Springs, Eric Loyer’s Strange Rain, Em Short’s Galatea, John McDaid’s Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse, The Perseus Project, the electronic edition of the OED, Michael Fraase’s Arts and Farces, and Paul La Farge’s Luminous Airplanes.

The “resources” category seems to do a reasonable job of covering the papers of ELO presidents past and present, but you won’t find any mention of work by Ted Nelson or Cathy Marshall, by Bob Stein or Polle Zellweger, by George Landow or by me.

Some of these precede ELO’s branding efforts or were created by people who didn’t go to those famous ELO parties, but the #elit hashtag doesn’t simply stand for the aspirations of a faction. We’re working on the future of fiction. And it’s past time to get back to work. I hear on Twitter that they’re still flogging the PAD report on preservation, which announced an ambitious technical program in August 2005 – open-source HyperCard, a universal XML dialect for digital literature, and more. It seemed to me to be unrealizable at the time and as far as I’ve heard, no one has done a lick of work from that day to this.

Meanwhile, on the real preservation front, we’re doing a ton of work here. its name was Penelope for iPad, Judy Malloy’s wonderful classic about art and AIDS, is in testing. We’re just getting started on two complete rewrites – re-envisionings – of Storyspace. And we’re hosting (and sponsoring) a meeting next month about Dangerous Readings – a weekend hackfest and international web art/science camp for writers and programmers and critics who want to get stuff done.

We’d welcome help. And I’m willing to help: I’m happy share what I know about the history, the technology, and the craft with anyone who is interested. My Rolodex® is your Rolodex. But I’d be happier if there were fewer obstructions. Muddying history doesn’t help.

Lori Emerson’s abstract for the next MLA begins:

It is remarkable that in just ten years, since the publication of the first book on electronic literature (Loss Glazier’s Digital Poetics in 2001)...

This overlooks Jay David Bolter’s Writing Machines, George P. Landow’s Hypertext, Michael Joyce’s Of Two Minds, Silvio Gaggi’s From Text To Hypertext, Jane Yellowlees Douglas’s The End of Books, and I shudder to think what I’m forgetting.

In other fields, it’s the Professors of English and the Librarians who play the role of dusty pedants. Sigh.

Updates: I was right to shudder. Titles I forgot include Richard Lanham’s The Electronic Word, Michael Heim’s Electric Language, perhaps Ted Nelson’s Literary Machines, and assuredly Espen Aarseth’s Cybertext. Lori Emerson responds, though not very responsively, by trying to argue that none of the early work really counted until the ELO’s branding effort. Publishers fixing MLA citations, English professors lecturing me about branding – what a country!

Everyone saw the focus, the insistence, and the scorn for bozos – for people who were happy enough to get by. What people always missed about Jobs at Apple was the agile mind, able and eager to shift from the inside to the outside and back again.

Apple was not saved by design or innovation. What saved Apple is the constantly iterated shift from design to execution, from surface to depth, from style to science and back again.

Jobs learned from bad times but did not let bad times shape him. When he was kicked out as a dreamy incompetent, he went elsewhere, made a couple of new fortunes, came back, and kept dreaming. When the press assumed that Microsoft would simply discontinue Office for Mac and let someone buy the wreckage at the fire sale, Apple stood on a hill before the setting sun and shook its fist at the heavens and vowed that it would never be hungry (and powerless) again. But Apple did not become a defensive shell or an outlaw.

The original iMac, Steve’s machine, was Bondi Blue. Everything else was business beige. A couple of months later, you could tell which galleries on Santa Fe’s Canyon Road were doing well because the prosperous galleries all had those Bondi Blue iMacs. Some were sitting on 17th century Spanish oak, some on polished steel, and some on two planks of raw pine thrown across a couple of old trestles – depends on the gallery – but if they were selling art, they were buying that iMac.

Apple built the iMac into a nice little business, and then wrecked its own business with laptops. Same thing with MP3 players: people ridiculed the new iPod as underpowered and overpriced, then watched in amazement as it consumed the entire sector. And watched again as it fought off every challenge until, once again, Apple demolished that market with a new kind of phone.

Mac OS was clearly a better UI package than its competitors. Rather than refine it, Jobs replaced it with Mac OS X. This required tons of work and a vast leap of faith, since a company that had always rolled its own foundations now learned to depend on Unix and Postscript.

The dramatic shifts – abandoning floppies, abandoning Pascal and OpenDoc and Java, embracing virtual memory, abandoning the PowerPC, abandoning CDs – masked a steady reengineering of everything. Compare today’s MacBook Air to the original. They look pretty much the same, but the new one isn’t just faster. It feels better: more solid, more durable. Remember hinge kits? Hinges don’t wobble anymore. (A visible side effect of the process is the maxim that every new Apple laptop has a new video connector.)

After Apple had brought color to computers and everyone else was trying to slap juicy colors on their cases, Apple seized white. Dell and HP kept black for themselves. This was pure style, but Apple has exploited that blunder for a decade.

Look at the Apple stores. The analysts thought they were the desperate indulgence of a washed-up hippie who didn’t understand business, and they turned out to make heaps of money. But they’re not just distribution and maintenance centers. Everything is geared to say, you can do stuff with Apple stuff. You. MicroCenter and Fry’s were exciting with their racks of components and motherboards, but Apple put Grandma right in the center of the store and – look at that! – you were standing there learning stuff about video production, along with Grandma.

Everyone knew that companies should build on their core competency. What does a boutique computer company know about retail? Apple went about it like building a new system, with a fresh package and style and innovative systems in the background. (Everyone thinks Lion is about the scroll bars, but blocks and Grand Central Dispatch are going to change everything in ways that matter a lot more than scrolling.)

Have you ever seen an Apple Store employee standing around, looking bored, waiting? That’s execution. It can’t have been easy to see why this is important, to convince people it matters, even to make it possible. It’s not something you can instill by walking around and asking programmer A whether programmer B is really a bozo, which was Steve’s original management skill. This sort of polish goes all the way down. You never see a pile of Apple products in the stores: the piles are in the back, out of sight. You never see money. Do they even take cash? There’s no cashier and no cash register.

It’s still going on, and the analysts still can’t follow the shift from outside to inside. The iPhone 4 was outside: new design, new display, new camera. Now, we do the inside, with a new fast processor. “Who needs a fast processor?” they wonder. You need it to do stuff, because phone software has only a few seconds to do what you have in mind. (Desktop programs like Photoshop can take minutes to load, but if an iOS app doesn’t get itself loaded in five seconds, the system assumes it’s run amok and throws it in the drunk tank.) And what do you want your phone to do? Well, Knowledge Navigator is a nice start, isn’t it? If you want to do speech recognition, you need a separate thread and a separate core – and look what we have here? GCD to manage the cores, and mobile processors with multiple cores and decent battery life. The action this year is inside.

And down the road, when everyone is finally looking at the inside again, you’ve got to think that Tim will remind us again that there’s one more thing...

Paul LaFarge in Salon on hypertext fiction and why the future of the book never happened.

Linked here without comment for the present.

Ryan Dahl, whose work on node.js is important, loses his temper about the state of software today.

I hate almost all software. It's unnecessary and complicated at almost every layer. At best I can congratulate someone for quickly and simply solving a problem on top of the shit that they are given. The only software that I like is one that I can easily understand and solves my problems. The amount of complexity I'm willing to tolerate is proportional to the size of the problem being solved.

I know the feeling, but it’s wrong.

We are not suffering from the consequences of some evil arbitrary blunder. This is how things are, the way the world in which we live is wired. Yes, water is inconveniently wet, and pi is hard to remember, and maybe we can solve those problems or maybe they are not in fact the sort of thing one can solve.

Railing against /usr/lib leaves you chained to a rock.

Complexity is painful. Along with filth and poverty and disease and death, we work against it, and we know we aren’t likely to get it quite right. There’s no shame in shaking your fist now and then, but it doesn’t help a lot. Better to go back to fetching fire.

Dahl concludes that "the only thing that matters in software is the experience of the user." This sounds great and says precisely nothing. What is the experience of the user? It might be any observable property of behavior of the software. Is the software pretty? That’s experience, sure. Is it easy to use? Experience. Does it give the right answer? That’s part of the experience, too. Does it do what you want to do, even if that’s not what everyone’s sainted aunt is likely to want? That’s a big part of your experience. Is it easy to extend and build and maintain? Developers are a big community, and making their experience better is a powerful way to make lots of stuff better. Everything is part of the experience of the user, because there is no user. (No hay banda, either,)

There is just us and the software and the world.

John Maeda reminds us that silly interview questions are bound to elicit silly answers. Asked how technology is changing art, he replied:

I think that computers and the advancedness of computers hasn't changed art very much. It's enabled more to happen. Again, that counts a bit more. Better resolution, longer lengths, more color variety, but all in all it's the same thing. It's what experience can I deliver to you that is provocative, that can change how you think.

This is true, of course: the art speaks, not the canvas. But it’s also misleading – especially for someone whose career has been so closely identified with new media – because changes in medium and style and technique all let us say new things, and let the audience see old things in new ways, and this is precisely how art has always changes how people think since Thespis had the idea of putting a second character on stage and turned liturgy to drama.

Are you the leaf, the blossom or the bole?

O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,

by Laurie R. King

After two dark books that told one dark story. Laurie King sends Russell and Holmes on a romp, sleuthing odd behavior in a British film production company. They’re filming a silent movie about The Pirates of Penzance, or rather a movie about a production of the operetta. Oddly enough, we’re filming on location – not in Cornwall, but in Lisbon and Morocco. Mary becomes travelling secretary to the troupe, responsible for the well-being and comfort of the thirteen daughters of a very modern Major General, a matching set of pirates who are surprisingly piratical, and also a half-dozen strikingly-handsome constables.

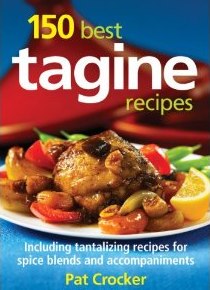

by Pat Crocker

A PR firm pitched this book to me with exceptional skill, and since I’ve been wanting to explore some North African braises and stews this winter, I went along. So far, it’s been a tasty trip.

The market-imposed format promises 150 recipes, so you’ll get your money’s worth. No one needs 150 recipes. First, we don’t want 150 things to cook, not unless we’re Carol Blymire or Julie Powell

. We want one or two new things to cook that are delicious and new and that we can vary along one or more dimensions when we’d like to change them.

The book starts with an exceptionally good and direct rundown on tagines as cookware, including a frank and supportive discussion of the comparative merits of Le Creuset and Staub adaptations that use new materials for Western kitchens. There are good discussions of North African and Mediterranean spices and spice mixes, too. What I miss here is a clear feeling for the difference between a tagine and a partly-covered cocotte or Dutch oven.

Similarly, it's not entirely clear to me, after casual leafing and after cooking a recipe or two, exactly how a tagine differs from other braising techniques – from what you might see in Provence, say. Is it mostly about spices? About cooking in water rather than stock and wine? About eating with your hands? About cooking for a very long time? Some questions of technique seem obscure, too; should we sometimes brown the meat but sometimes not? Should we brown vegetables?

Despite these objections, last night’s lamb, stewed for hours with apricot and pear and lots of berbere – a new discovery for me – was very tasty indeed. And, despite the unpromising cover, it wasn’t underspiced or timid, but had lots of full-throated heat and depth.