- Gougéres and Last Words

- Eggs Copenhagen, with home-made muffins, Champagne

- Seven-hours lamb, with chard and kugel, Australian GMS

- warm cake with hard sauce

- old movies

- a fresh year

One aspect of Tom Service’s brilliant tour of the ills of contemporary classical music rings familiar to students of new media.

If a band that you like has a new album out, your dominant emotion when you download is one of potential excitement....With a few august exceptions, it seems to me to be often exactly the other way round with our little world of contemporary classical music, where the expectation and even the desire on the part of the audience is that the new piece won't be any good. That's because the audience are often the composer's competition.

It’s not that bad in new media, at least outside the most toxic corners, but the problem is real. When we hear about a new work in new media, we don’t rush to read it, we don’t chatter about it, we cheer or jeer it based on ancient alliances and enmities. The most recent words that Giselle Beiguelman (Wop Art, Code Up) said to me, in a lovely bistro in Germany, was that the work of our hypertext writers and poets seemed really interesting to her, but alas she wouldn't read them because they weren't all open source. This isn't art, or research. It’s politics.

I gave a paper at Florida, early this year, to a small, select audience of some of the best critics and scholars of the field. I pointed to the urgent need for criticism, for smart people to write intelligently about new media work. In the question period, Joe Tabbi (University of Illinois) argued strongly that the ELO directory would marshall armies of students to write terrific criticism. In the months since its relaunch, that little list has hardly grown; 159 entries in June, 178 today. Most of the additions are stubs contributed by the authors of omitted works. I mentioned two dozen famous but missing works, and most are still missing. Where are the term papers?

This is no fun.

He fell into a pot!

He said, 'Do I like this?

Oh, no! I do not.

This is not a good game,'

Said our fish as he lit.

'No, I do not like it,

Not one little bit!'

So, we’re going to start 2011 at HTLit.com by talking about a lot of terrific new media. Every few days, we’re going to highlight a different piece. Some will be brand-new, some 20 years old. Some will be very textual, some visual. Some will stay put, others move, and others require you to come to them.

It’s time to enjoy new media again. Back to the kitchen, folks!

Happy New Year.

David Millard writes a defense of the academy against British budget cuts. Robert Reich decries the attack on American education.

Via Michael Druzinsky, a fascinating lecture on the end of music: So long, and thanks for all the noise: 2010 and the end of musical history, by Tom Service.

And after decades of new musicology and new history, we all realise, if we didn't know it already, that all of those grand teleological ideas of how music progressed from Palestrina to Bach to Beethoven to Brahms to Bruckner to Schoenberg to the Beatles – something like that anyway – are all bunk. What I'm not saying, so it's there for the record, is that music is over in 2010. Just the opposite, even if it'll take a few minutes to get to how that could be true.

by John LeCarré

We return once more to the old, familiar interrogation rooms of The Looking Glass War and to vintage LeCarre in this sad, compelling, and brilliant story. An athletic Oxford don and his beautiful girlfriend, a fledgling barrister, visit Antigua for an indulgent tennis vacation. Their tennis turns out to be beyond the league of the typical Caribbean tourist, but near their resort lives a wealthy Russian who plays a very strong game indeed and who leads the couple into unexpected thickets and, soon, to basement interrogation rooms. LeCarré has a remarkable knack of drawing minor characters who are vivid but not merely idiosyncratic, whose peculiarity is the most natural thing in the world.

by Alaya Johnson

This dazzling tale of Jazz Age New York centers on Zephyr Hollis, a girl from the West who teaches English to impoverished immigrants, volunteers at a blood bank that caters to indigent vampires, and crusades against corruption, crime, and intolerance directed at Others. A promising story by a new and very promising member of the Interstitials.

I’m fascinated by Andrew Sullivan’s weekly contest, View From Your Window. Each Saturday, he posts a picture of the view from someone’s window, and invites readers to identify, as precisely as possible, where the picture was taken. The best answers are posted the following Tuesday. Here’s an example:

Most weeks, readers identify the photographer’s precise location. This is remarkable enough when the picture shows an unremarkable suburban street in North Carolina or an office building in Paris, but readers also manage to locate obscure villages in central Asia.

This picture turns out to be the former RCA Victor building in Camden, New Jersey. The winner pinned the exact address in ten minutes.

The winners are not professional detectives or CIA photo-analysts. Occasionally, they benefit from happenstance: one week’s photograph, a view of a college quadrangle, was solved by a student who happened to be sitting in the library from which the picture had been taken. More often, though, the solution depends on patient and clever search to identify small details: the color of the label on a recycling bin, the spackled bullet holes in an old wall, the shape of a smokestack on the horizon.

Sam Spade couldn’t do this. Sherlock Holmes could recognize a particular clay because he himself had seen the claybed, but surely could not identify mundane scenes he had never witnessed. Even the resources of James Bond would be taxed. Yet, with the aid of Web search engines and ingenuity, hobbyists routinely solve these, week after week.

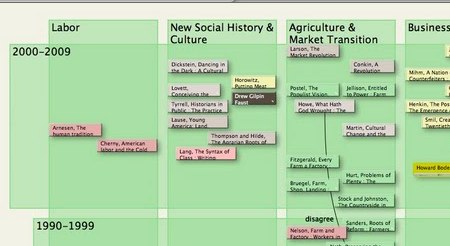

Anticipating the upcoming meeting of the American Historical Association, Dan Allosso describes Tinderbox for mapping the relationships among historical accounts at the blog of The Historical Society.

Yahoo is abandoning the del.icio.us bookmark service.

This seems odd, because they paid a lot of money for delicious, and because – as far as I hear – it seems to run well, getting heavy usage at modest expense. It’s not bringing in money, but it commands some mindshare, and Yahoo paid a lot of money for it not long ago.

One great difficulty in business right now is the following cycle:

- Startups create novel services with challenging new business model

- Founders cash out in sale to large firm for lots of money

- Large firm subsequently finds itself with an asset it cannot quite exploit

- Because the large firm is so large, it simply writes off the purchase and discards what it purchased only a few years ago. To the large firm, the whole transaction is a distraction.

The result is simply destruction of wealth: we start with a nice little business, and we end up with nothing. It’s not just Web businesses and not just lack of monetization; I’ve seen this happen, for example, with consulting firms that were profitable from day one.

If you were discarding steel and glass and Aeron chairs, people would pick them up off the sidewalk and reuse them. But when you discard a service organization, there’s nothing left; it’s all up in smoke. What a waste.

by W. E. B. Griffin

Years ago, I found myself writing a lot of complex hypertext software on very slow computers. Compilation took minutes – too little time to take up a fresh task, and too long to stare at the screen. Griffin’s Brotherhood of War series, found at the library across the street, worked well for this; engaging, episodic books that lend themselves to reading in short snatches and that have enough narrative coherence to keep the reader engaged, yet not so much excitement as to distract from the work at hand.

Returning now, I found the book just as enjoyable as I remembered. In many ways, this is a rough draft for Griffin’s later series, The Corps, which swaps out the Army for the Marines. Indeed, at the end of The Corps, we even visit some of the locations where The Captains gets started. There’s lots to dislike in Griffin of course, especially his belief that inherited wealth lends one inherent nobility, but these books aren’t meant to be taken seriously. They’re meant to be fun, and they are.

The blog for Ms. Magazine features an Advent Calendar with a daily feminist treat. The treat for December 13, selected by Aviva Dove-Viebahn, was Shelley Jackson, author of Patchwork Girl.

Hidden Kitchen provides a wonderful example of the thought behind creating a wonderful new dish. In “Making America Proud”, they want to make a terrific baked potato, inspired by fast-food but refined until it reaches a platonic ideal.

As we saw it, the perfect baked potato had six essential elements; potato, bacon, broccoli, chives, sour cream and cheese. Each of these six components served a specific function in the overall success of a dish; potato for neutral volume, bacon for salt, broccoli for refreshing bite, chives for cleansing, sour cream for tang and cheese another form of salt and a somewhat unctuous mouthfeel.

You could go to Wendy’s, of course. But Hidden Kitchen wants to refine this. In place of bacon bits, for example, they start with

a braised pork belly that was slowly cooked over four hours. We then pan seared the belly in cast iron until the outside was crunchy but the center remained fork tender.

To make a warm cheese sauce, they start from a bechamel. Naturally. But now we have an elegant white sauce and “this dish needed some melty, neon, Wendy’s-esque sauce” to really get that American fast-food spirit going. And what would deepen the flavor? Some turmeric for fluorescence, and some smoked paprika for color and earthy spice.

Kudos to Swedish hosting company Servage for dropping a pirate site we brought to their attention, a site that was plagiarizing ad copy and artwork of software developers in order to promote pirated software.

It took a lot of correspondence – too much, in my opinion – but it is always a good thing when hosts enforce their terms of service. Perhaps, if we make setting up pirate sites a little bit less convenient for attention-hungry kids, we can create a better community.

Frank Rich reminds us that the Republicans have forced the Smithsonian to remove David Wojnarowicz’s Fire In My Belly from an exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery.

This morning’s Globe reports that GOP Senator Scott Brown has received $140M in “donations” from banks who want to block regulations. What a country!

David Wojnarowicz also wrote When I Put My Hands On Your Body, the concluding lines of which were quoted in Blade Runner and have become one of the iconic moments in modern science fiction:

All these memories will be lost in time like tears in the rain.

In honor of finishing Julie & Julia, I thought it might be fun to make one of the handful of dishes that Julie Powell seems to have actually enjoyed, rather than endured, in her mastering the Art of French Cooking: croustade de champignons et œuf poché. I’ve been thinking about making something in a croustade – a little free-standing pie crust that holds your dinner – ever since that Alinea adventure with its Pigeonneaux a la Saint-Clair . But the pigeonneaux is an incredibly involved classical preparation involving poaching tiny squab breasts and making the legs into tiny little mousselines, and it’s way out of my league. I already had some very fresh eggs from our farm share. This sounded like fun!

It wasn’t.

The crust rolled out just fine. I tried folding it into my muffin tins, just the way Julie had. But the muffin tins looked too small. Maybe Julie has big muffin tins? My muffin pan makes dinky muffins, too. Julie probably has a better muffin tin.

But I have ramekins! In two sizes! And that’s probably more authentic, anyway. So I used the ramekins instead. I tore one of the little croustade crusts trying to refold it, and had to patch it up. OK: it’s that kind of day. I put the ramekins in the refrigerator to chill – a step I tend to forget with pies. I didn’t forget this time! I was hot stuff. I was cooking with gas.

Julie complained that she should have used pie weights. Julie had no pie weights. But not me: I was prepared! So, I weighted each little croustade with a handful of pie weights, and popped them into the oven.

And then I started sautéing the mushrooms (garlic, olive oil, plenty of salt), halving and parboiling some lovely fingerling potatoes for a side dish, and boiling the water for poaching the eggs. And I started to gather the ingredients for the sauce choron Fresh tarragon? Check! Shallots from the farm? Check! Butter? Not really as much as Julia would want, but probably enough for a half-yolk bearnaise if I don’t screw it up. Check! Tomato paste?

No tomato paste.

About this point, a vague sense of doom started to seep into the kitchen. There was no tomato paste, so no lovely rosy-fingered sauce choron. How could there be no tomato paste?

OK: the dish doesn’t really need a fat-based sauce. And I could get by with hollandaise or bearnaise, right? Hell, if you google this dish, you’ll find someone suggesting that the modern Julia would serve the eggs on hunks of bread. If Julia wanted you to use a crouton, she would have suggested one. There’s a name for that dish: poached eggs on toast, side of ’shrooms.

So, I dithered about the sauce. No need to jump on it right away. I thought a quick peek at the croustades, just to admire them and make sure they weren’t scorching might improve my morale and dispel the sense of doom.

I considered the advantages of mixing a stiff drink instead. That might have been a better idea. For three of the four croustades had slumped into misshapen folds in the bottom of their little white ramekins. The fourth was neat and round and nicely brown and mocking in its near perfection.

It was time to get the pie weights out, anyway, I thought. Besides, with the croustades slumped over, the weights were in danger of being baked into the pie. So, I tried to pour out the pie weights, and the whole croustade came with them – in several distinct pieces. And there were no spares.

OK: I fished out the pieces, swore, threw them back in the ramekin, and tried to extract the pie weights more carefully from Failed Croustade Unit (FCU) #2. This ended in the same fiasco. FCU #3 yielded more easily, so it remained in one misshapen piece instead of a pile of torn fragments.

Then I turned to extract the weights from that one, successful croustade. The crust was perfect -- and in this one, each pie weight had burrowed into a buttery little nest, surrounded by pie crust. I tried extracting them, one by one, with a little spoon. No dice, just torn crust. I tried tongs. I tried tweezers. I was not happy, and the croustade was no longer very perfect. So FCU #3 no inherited the proud mantle of being the one that wasn’t totally ruined.

In the end, we had roustade de champignons et œuf poché consisting of a later of pastry fragments (bland but adequate), a scattering of sautéed mushrooms (delicious but far from sufficiently numerous), and a poached egg. I liberally buttered the four nonstick egg poaching cups , since there was no way in this mood was I going to attempt freeform poaching and my nonstick egg poaching cups always ruin poached eggs. This time, only one of the four eggs was ruined, though two were overcooked.

I bailed on the sauce. Ruhlman says that hollandaise can smell fear. I suspect the amount of cursing might have made the hollandaise blush, but the better part of valor suggested that we didn’t really require more butter.

So, it was a total mess, but we ate it, I didn’t quite crack a tooth on the covert pie weight that got away, and on the whole it tasted good and looked like something rustic and tasty.

McGee draws a really useful distinction between city meat and country meat.

In the countryside, people lived alongside farm animals that pulled a plough, laid eggs, or cleaned up inedible scraps. Eventually, these animals wound up in the cookpot. They were mostly old and had done lots of hard work, their meat was flavorful but tough, and so they had to be slowly braised or stewed.

When people started to live in towns and cities, their meat had to be brought from the countryside, and had to be raised specifically for market. City meat is young, because it’s raised for meat, not work, and so city meat is more tender. Some cuts, like beef filet, epitomize city meat, emphasizing richness and tenderness, and these are the cuts most people see in the supermarket. We can grill city meat, or sauté, or stir fry.

Modern trends favor city meat, and city meat is what most people know how to cook. City meat works well in restaurant settings, too, because it’s easy to prepare each serving for each individual customer. Country meat is trickier in a restaurant because we need to start cooking hours in advance.

It might seem that country meat is hard for busy people, too. It does require planning a few hours ahead. But where city meat needs your undivided attention while it cooks, country meat is happy to take care of itself, to sit and simmer or smoke or marinate for hours while you are doing more important things. And while today’s city meat dishes are tomorrow’s leftovers, country meat is product that you can use in different dishes over the coming days and weeks. One braised pot roast or one grill-smoked turkey can be the foundation for three or four meals, all fresh and new and each of them unique. Tonight we have pot roast with its tasty vegetables, in a few days we can shred the rest of the meat and make a ragu with lots of tomatoes and mushrooms, and next weekend we use the bones and scraps and leftover juices to make stock for risotto.

by Julie Powell

The record of the making of one of the great Quest Blogs:

The Book:

"Mastering the Art of French Cooking". First edition, 1961. Louisette Berthole. Simone Beck. And, of course, Julia Child. The book that launched a thousand celebrity chefs. Julia Child taught America to cook, and to eat. It’s forty years later. Today we think we live in the world Alice Waters made, but beneath it all is Julia, 90 if she's a day, and no one can touch her.

The Contender:

Government drone by day, renegade foodie by night. Too old for theatre, too young for children, and too bitter for anything else, Julie Powell was looking for a challenge. And in the Julie/Julia project she found it. Risking her marriage, her job, and her cats’ well-being, she has signed on for a deranged assignment.

365 days. 536 recipes. One girl and a crappy outer borough kitchen.

How far will it go? We can only wait. And wait. And wait…..

This is a wonderful start. Compare:

That slepen al the nyght with open eye

So priketh hem Nature in hir corages-

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes.

Powell embarks on this quest knowing that she is searching not for the Macguffin but for some better idea of what she should be doing. “I went into the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

This is a fine book. One might wish it took more pleasure pleasure in the food and that Powell had more fun cooking it; what remains in memory (or what makes good copy), it seems, is the anxiety about eating so much top-quality butter and, of course, the disasters. But the disaster was central to the weblog as to the Project; failure is what makes drama dramatic. We might admire the young woman who is cooking a lot of French food, but it is only when her marriage is falling apart and the cats have eaten the last of the chicken and she’s going to be fired and when she has to know right now where can you find marrow bones in Manhattan anyway because her mother is coming to dinner – when everything is at sixes as sevens and Julie is ready to collapse in tears – that the weblog audience reaches through the fourth wall and transforms the medium into something new.

Nicholas Carr argues that interactive storytelling is an oxymoron, picking up the torch where Sven Birkerts

dropped it by reviewing what he has not read and ridiculing what he doesn’t quite understand.

Carr is responding to a Craig Mod essay about the future of writing which briefly alludes to wikipedia before proposing that the real impact of the digital has been on process, not form. Everyone who writes knows the impact of new media on the way we write. We’re far freer in structural edits today than we could be in 1950 or 1812, because we all have word processors and some of us have Tinderbox and Scrivener. Every novelist has a Web presence. Everyone who writes for a living either uses a computer or abjures its use as a dramatic, performative act. Old ideas like serial publication seem, suddenly, to be attractive once more. All this is unremarkable. One suspects that Carr got as far as “wikipedia,” through the printout across the room, and started to rant.

Carr seems to think that, when people talked about “death of the author,” they were concerned with some vague idea that everybody should invent their own wikistyle exquisite corpse

stories. Yes, a few people have played with that idea, and it might yet be productive, but that’s not what people were talking about.

What those Evil French Theorists were discussing was the Late Modernist and then Postmodernist realization that the meaning in stories is more complicated than it would be if reading were simply data transfer, if it were just a matter of decoding some symbols that the author put on the page in order to evoke a specific response. Proust’s madeleines mattered to him because they triggered memories of sunny days when he was small, and that shudder of revulsion that you, dear reader, experienced when I mentioned Proust, matters because you never did finish that paper, did you?

“How did he know?” you ask. “And how did he know I still blush to have disappointed Dr. Baring, so many years ago?”

I didn’t. It’s smoke and mirrors. All storytelling that matters depends on this trick of memory and identification. It always

has. We tear apart

the story and piece it together; that’s how it works. We always knew this, but nobody quite explained it before the generation of Barthes and Derrida and Calvino.

Carr concludes that

An encyclopedia article can be "good enough"; a story has to be good.

A critic, looking for something good, might take a look at afternoon, a story. Or Patchwork Girl. These hypertexts are good, and they show one way to do it. There are others. You could do it yourself.

The tech world has a columnist, Rob Enderle, who seems always ready with a prediction that Apple has just made a terrible blunder. This makes him useful to newspaper editors who need a quote by deadline and don’t care whether it’s right, as tomorrow it will be fish wrap. Nick Carr is becoming the Rob Enderle of literature.

I gather that weblogs of discussion forums – perhaps specifically eGullet – played a significant role in forming an audience and aesthetic for the current cocktail revival. Online discussion of forgotten drinks like the Aviation (and its creme de violette) and Pegu Club (and its two kinds of bitters) helped grow a clientele for places that take cocktails more seriously, for recovering forgotten flavors. (Advance cheers and toast, incidentally, to Erik Ellestad, who is approaching the completion of his astonishing quest blog in which he samples and writes about every single recipe in the Savoy Cocktail Book.)

One key facet of this discussion was the realization that old ingredients were not necessarily identical to what we find on the shelf today. Today’s Lillet, for example, is not nearly as bitter as it was when James Bond ordered his Vesper. Some changes in manufacturing are abrupt, but other changes might be gradual. How big were Hemingway’s limes? How sweet were the lemons at Harry’s Bar? And how old-fashioned was the sugar they used in an Old Fashioned in the old days?

The cocktail people were free to research questions like these because their focus is so tight. I suspect, though, that there’s a lot of scope for exploring this in thinking about classic cookery. Our meats have changed considerably, and our flour has probably changed even more, since Escoffier was young. I wonder what we could learn from similar explorations of old kitchen ingredients, and whether Achatz is thinking about this in his exciting historically-flavored restaurant.

Chad Harbach explores the conflict between two writing cultures: the war of the New Yorkers vs. the MFA’s.

For the MFA writer, then, publishing a book becomes not a primary way to earn money or even a direct attempt to make money. The book instead serves as a credential. Just as the critic publishes her dissertation in order to secure a job in an ever tightening market, the fiction writer publishes her book of stories, or her novel, to cap off her MFA.

Telecom software designer David Bradford talks about the role of Tinderbox in his work.

"I love my job and love the discovery portion of it. The single biggest worry, the thing that keeps me up at night, is the thought of missing an important piece of information, and not considering it during the design. This can lead to very costly rework and extend time cycles into unacceptable ranges."

"What can I do to minimize the risk of leaving an idea, a thought, an essential component laying on the floor? "

by Richard Wrangham

A pleasant reconstruction of what we know about everyday life in the Pliocene, this small book offers a compelling argument that one key (and very early) driver of the transition from apes to people was the discovery of cooking. The effects of cooking on the diet of Homo Habilis would have been profound. Instead of dedicating 6 hours a day to chewing, as monkeys do, the cooking ape was free to explore hunting, honey-finding, and all sorts of other pursuits. Even if the big one got away, you could come back for a home-cooked meal which you could eat before dark or by firelight. That meal would be a lot easier to digest than raw foods are, and so the cooking ape could make an early night of it and be ready at dawn to go gamble some more. Wrangham sometimes pounds his points to splinters, piling on facts long after we’re as convinced as the necessarily-thin evidence will permit. I was surprised that there’s no discussion of protein evolution or DNA sequencing, and wish I knew whether it was omitted because there is none or because it was thought to be too technical for the projected audience.

by W.E. B. Grifiin

Reading one W. E. B. Griffin seems to lead me to reread another. This is the prequel to Retreat, Hell and it’s plenty of fun.

I’ve got a stack of books about three feet high. I’ve got an overdue book to write, three major software projects to design, and a marketing campaign to run. I’ve got a research paper due in six weeks, and I just agreed to a book review that’s due in the same time frame. Why, exactly, am I reading this additional, 500 pages of narrative delight?

I always had this dream that Harry Caray and Ron Santo called a ballgame together. Maybe next season they will. Maybe some season I’ll hear it.

At lunch, I’ve been reading the 2002 Julie/Julia blog in chronological order. She can write.

We’re not seeing the energy and excitement of early blogging these days, and it behooves us to understand why. Is the change an illusion, an artifact? Have we simply become accustomed to weblogs, so what once seemed exceptional is now par for the course? Are we looking in the wrong place?

Here’s Julie:

I stir in beaten egg yolks and tablespoon after tablespoon of butter – as much butter as the sauce can hold. I beat it constantly over a very low heat, and it thickens. I beat in the tomato paste. It’s a gorgeous warm red color, and I had never much like tarragon before, but this tastes lovely, fresh and rich at the same time.

Fuck! The pastry cups!

I manage to yank them out of the oven just before they go over to burned. Now all I have to do is reheat the eggs and the mushroom sauce, and we’re done.

“Eric, have I mentioned how much I really, really appreciate that you haven’t divorced me yet?”

“Where’s the corkscrew? Let’s get this damned wine open.”

The time is eleven forty-five. I heat everything without incident. I put two pastry cups on two plates. I spoon some mushroom sauce into each cup, then an egg, then a large spoonful of sauce Choron. They are things to behold – gaspingly lovely, very impressive. It is midnight on the dot, and my husband and I are eating Oeufs en Croustades a la Bernaise.

They are as lovely to eat as to look at. The runny yolks break open and meld with the sauce and the mushrooms, but the flavor of each element remains distinct. The pastry cup, though not flaky like it should be, is buttery and crisp and holds the whole thing together.

Two, as it turns out, is entirely too much.

By one am we are in bed, French eggs churning in our bellies, due to awake in five and a half hours. I’m fucking exhausted. But happy. Those eggs are what the Julie/Julia Project is all about. I daresay they’re the one thing in my life lately that has worked out just perfectly.

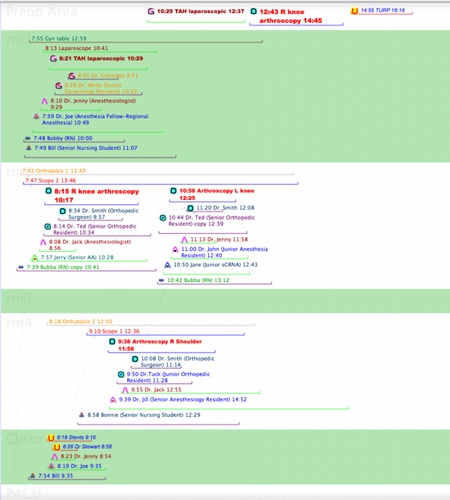

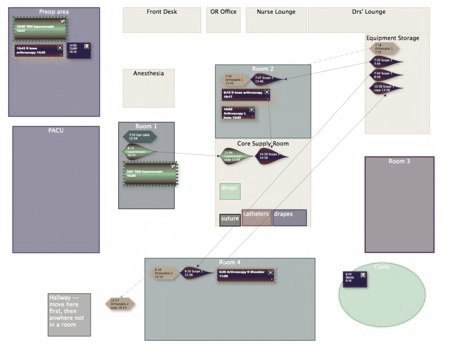

Brian Gregory uses Tinderbox to explore operating room scheduling.

Operating rooms are expensive assets; you don’t want them sitting idle when people need them. Each room may be equipped differently; you want to schedule procedures in the most appropriate room. To complicate matters, some procedures require special equipment that takes time to move from place to place. You don’t want to haul a ton of equipment across the hospital if you don’t have to, and it’s good to preposition things at your leisure, rather than having everyone wait while someone fetches a cart from storage.

Dr. Gregory combines the Tinderbox map view, which provides a convenient spatial perspective with just the right level of abstraction, with Tinderbox timelines. The timelines show conflicts and bottlenecks, and the map view helps the staff figure our where things should go and where people should be.