Over in the Tinderbox forum, J. P. Bogers MD Phd asks why software companies are cagy about release dates. Why isn’t Tinderbox 5 out yet? Why don’t well tell you exactly when it will ship?

When I build a house, the contract mentions a delivery date (and even a fine when this is not met), when I buy a car the same. As a medical professional I run a lab with thousands of tests each year and the QA system only allows a small percentage of specimens to be answered after more than a specified number of days.

The answer, simply put, is: “This is research.”

New houses are built every day. Before the builder picks up a hammer, there are detailed plans and specifications that indicate almost every detail. And, though your house may be unique in overall plan, nearly everything in it has been built into houses before.

Tinderbox is a personal knowledge assistant for visualizing, analyzing, and sharing short, textual notes. There have been other systems with similar goals, but they are not numerous. I have probably met the majority of the people who have ever designed a system in this area. In many ways, this more closely resembles 18th century natural history, or 19th century medical research, than managing a medical testing lab or a house construction site.

Software development is made still more complex because we have not yet discovered an equivalent to trim -- the myriad tricks and conventions that allow a builder to make substantial errors in measurement and constructions without damaging or complicating the final product.

At Tinderbox Weekend dinner last night, we were talking about the original design of Tinderbox's export templates. I had developed what I thought to be a very clever scheme for HTML export based on a declarative language (something like CSS, which had not yet been invented) augmented by machine learning. I presented this to Jocelyn Nanard, on whose work at Montpelier the AI component was based. She listened patiently, said at once that she had a better idea, and set out the outline of the current export template approach. We wound up with quite a few distinguished researchers -- M and J Nanard, D Schwabe, F Garzotto, R Trigg -- around the table for an impromptu seminar.

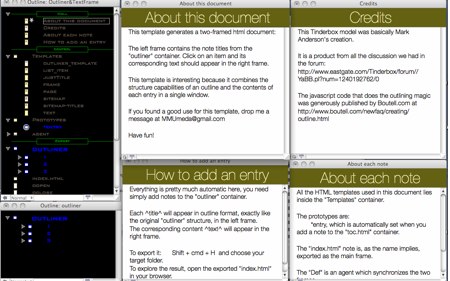

And we didn't get close to today's design. None of us really foresaw how large an export language people would want to have, and so tags multiplied over time. We did not anticipate how useful agent actions would be, and so we didn't anticipate that the template language could depend on the action language. Nobody mentioned the envelope-letter idiom, which turns out to be central to really effective export definition.

And nobody talked about performance. I knew that Tinderbox would be built around attribute-value lists with inheritance, but I hadn't discussed this much that evening. It didn't seem to be the right concern for this group. My rough estimate of the number of inheritance-tree dereferences suggested that performance might, perhaps, be acceptable. My back of the envelope calculation was orders of magnitude off; only when the system was running did we discover that exporting a complex weblog design like this one might well require a million attribute references. Conversely, I didn't then know that we'd be using prototype inheritance; I don't think Noble's book was out yet but in any case I hadn't read it.

I do recall talking with Nanard about the nice performance of the new PowerPC processors for recursive descent parsing. Of course, we no longer depend on those processors -- and we don't use a recursive descent parser for export template anyway.

When a construction project falls behind, you can often add more workers to catch up. Not always, but often – and we have excellent tools for knowing when we can add those workers and were they will do more good. When a testing line falls behind, we can add instruments, or increase their throughput, or build and staff a second line. None of this works in software. At the first hypertext conference in 1987, we had a keynote from Fred Brooks Jr., then incredibly senior and aged, a sage who literally wrote a book about this problem. He’s still talking about it – I heard him again at OOPSLA right before my NeoVictorian sermon. We still have no good solution.

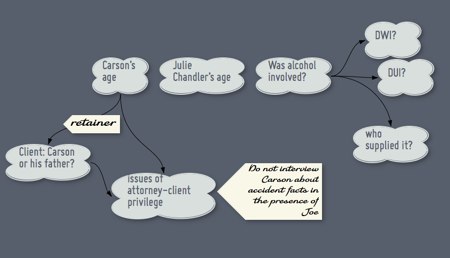

In our development schedule, as it happens, there’s a task called The Bogers Email Crash, which originates from an email Dr. Bogers sent some time ago with respect to Tinderbox's email features. The original report seems simple: receiving a particular email crashes Tinderbox, which of course it should not do. But in the event, we believe the problem lies in (of all places) a facade of the thread manager, a legacy multitasking controller on which parts of the POP protocol stack depend. And so we need to explore this notoriously intricate corner of the framework and operating system to find an issue that isn’t even our fault, code around it, and fix it — without breaking anything else.

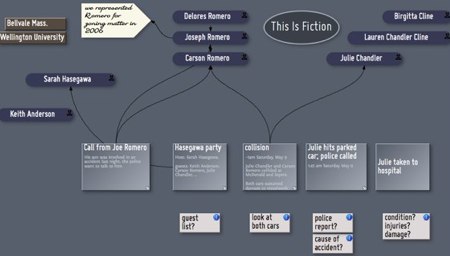

Finally, systems sometimes interact in complex and subtle ways, or raise design issues nobody anticipated. At Tinderbox Weekend yesterday, market researcher Tom Webster described a terrific approach to qualitative analysis coding that in which he explodes a transcript into elements, makes aliases of the elements, and drops them onto adornments as a coding gesture. These features work together very well indeed, but they weren't designed for this. Aliases[1] come from a rejected Web Squirrel design, returning to one of Doug Engelbart's ideas from NLS by way of the old MacOS Finder. Adornments come from Trellix, thanks to a terrific talk by Juliane Chatelaine, but the idea of adornment actions was not in the design or the design rationale and was, I think, an end-user suggestion. The details of the gesture -- being able to drag aliases out of agents, the impact of aliases on the mathematics of map updates after deletion, the distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic attributes -- all depend on ad hoc research that had to be conducted in the middle of development.

It takes time because we don’t yet know what we’re doing, because nobody has done this before.

[1] A question for my colleagues: were aliases in the Dexter model? I can't recall, and I've got a Tinderbox Weekend session on Tinderbox export techniques to chair in a few minutes. Email me.