An Android developer’s perspective on How To Get Developers To Fix Stuff.

Russian paleontologist Kiril Yeskov reimagines The Lord Of The Ring and its aftermath by assuming that Tolkien’s story is, in fact, merely one side of the argument. In this version, Mordor is not evil, but a civilization that opposes reason to magic, preferring justice to the law of nature. The desolation of Mordor is merely the unfortunate outcome of an early ecological disaster, a massive irrigation project that went wrong.

After a few years of bumper crops the inevitable happened – huge tracts of land were rapidly salted, and all attempts to establish drainage failed due to high groundwater levels. The end result was an enormous waste of resources and massive damage to the country’s economy and ecology. The Umbarian system of minimal irrigation would have suited Mordor just fine (and been a lot cheaper to boot), but this opportunity had been irretrievably lost now. The masterminds of the irrigation project and its executives were sentenced to twenty-five years in lead mines, but, predictably, that did not help anyone.

Mordor tried to deal with an ecological problem with an ambitious plan. When it failed, the war-monger Gandalf and the imperialist elves seized the opportunity to attack.

Caravans of traders went back and forth through the Ithilien crossroads day and night, and there were more and more voices in Barad-Dur saying that the country has had enough tinkering with agriculture, which was nothing but a net loss anyway, and the way to go was to develop what nobody else had – namely, metallurgy and chemistry. Indeed, the industrial revolution was well underway: steam engines toiled away in mines and factories, while the early aeronautic successes and experiments with electricity were the talk of the educated classes. A universal literacy law had just been passed, and His Majesty Sauron the VIII has declared at a session of parliament (with his usual ton-of-bricks humor) that he intended to equate truancy and treason.

The main action of The Last Ringbearer begins with small bands of orcs and trolls – our protagonists are a research engineer and an army medic – desperately trying to avoid ethnic cleansing at the hands of merciless elven hunters.

This analogy to the former Soviet Union and to the dream of rational Socialism pervades the early chapters, which move effortlessly from political accounts to a brilliant military history of the Pelennor campaign, focusing on the strategic decisions made by Commander-South, who in Tolkien is the chief Nazgûl.

The author of The Last Ringbearer is extremely knowledgable and invariably respectful of Tolkien’s work. This is no juvenile satire like Bored of the Rings. A few trivial mistakes do creep in – several meetings take place in the tower of Amon Súl, which was destroyed more than a thousand years before – and some names are misspelled, presumably because the Russian orthography differs: Cirdan the elven shipwright becomes Kirden, Celeborn becomes Cereborn, Linden becomes Lindon.

The middle portion of the novel devolves into an espionage story which, while competent, would fit equally well into any fantasy context or, indeed, into World War Two. In this section, which takes place south of Gondor in Umbar and Harad – that is, nearly off Tolkien’s map – we are reminded again of Tolkien’s extraordinary ability to choose names. Yeskov tries, but his invented Elvish names sometimes belong in Rohan and his Umbar names – which include characters named Jacuzzi and Makarioni – don’t work at all.

Yisroel Markov’s translation is terrific when dealing with history and workmanlike when describing the refugees of Mordor. The language of The Last Ringbearer loses the Elizabethan cadences of Numenor; in Mordor, we prefer plain talk.

The elvish dialogue is hopeless.

Clofoel of Tranquility: Haste is advisable when hunting fleas or dealing with a sudden bout of diarrhea, esteemed clofoel of Might. So please don’t urge me along: Trolls are tough guys and I’ll need a significant amount of time to get reliable information out of him.

Lady Galadriel: How much time do you need, clofoel of Tranquility?

Clofoel of Tranquility: I believe no less than three days, o radiant Lady.

Clofoel of Might: He just wants to give his bums under the Mound of Somber Mourning something to do, o radiant Sovereigns! This is so simple – let him use his truth potion and that spawn of Morgoth will spill his guts in a quarter-hour!

Lord Cereborn: Indeed, clofoel of Tranquility, why don’t you use the truth potion?

“Clofoel” is an invented Elven title, but it doesn’t sound like Sindarin at all, at least not to my ears. The invented Umbar lexicon is worse: “umberto” for the law of omerta is bad, and “Corregidor” for a minor official, while authentic for 15th century Spain, will inevitably be misread as the Philippine island.

But these are details, easily remedied or overlooked. To add to the Russian overtones of this remarkable book, it is not commercially published but circulates in Web-borne samizdat editions.

Ebert: You can draw.

Not long after that I found myself in London, and bought a Daler sketchbook and a drawing pen. This would have been in the art supplies store across the street from the English National Opera. I settled down in a nearby pub and began to sketch a glass, which is no more than an arrangement of ovals and lines. I continued to draw throughout the 1990s. I loved the British tradition of watercolor paintings and had already started to collect Edward Lear. At the famous Agnew's gallery on Bond Street, I was befriended by a cheerful woman named Gabriel Naughton, who told me I should buy some watercolor paints and try them for myself: “That will help you appreciate how good these artists are, and what they're up against.” I did, and they did. I realized in a practical, first-hand sense, with my own fingers, how precise and unforgiving watercolors are. Oils and acrylics can be repaired. Although you can daub up some watercolor with a tissue, you are essentially painting in the moment, and trying to get it as right as you can.

Originally written for my week guest blogging at The Atlantic.

Whenever I go to the theater or the symphony these days, I risk another standing ovation. Boston audiences are especially prone to jump to their feet for artists from storied places far away, such as Manhattan, but you see it everywhere. We don't trust our judgment and we don't trust art to be itself: we insist on that everything be a world-class, once in a lifetime marvel.

Great performances are performances that were great for you, at a particular time and for a specific audience. I once saw a Noel Coward's Private Lives performed in the basement of an Australian library, and it was incredible; every joke worked, every line sang.

Because we want every museum visit and every concert to be perfect, we've grown conservative and timid. We don't hear new music or see new plays, and most of us don't read a lot of new media. It's a blunder: famous names, costly tickets, and huge crowds can't always get you what you want.

When everyone went down to the theater to see what Aristophanes was doing this year, the artist knew a lot of the audience and the audience knew him. Next month, I'm finally going to get to hear Michael Druzinsky's symphonic composition, Roslyn Place. I've known Druzinsky for years. I knew Roslyn Place, the street where he lived. Less focus on best-sellers and more focus on connection would reward us all.

One pathology of our current Web is that people can make money selling vast numbers of worthless ads views. The payment for exposing you to an ad is derisory, a fraction of a cent, but if you can get millions of viewers, it adds up. This further focuses our attention on things we don't care about – silly celebrity sex stunts – at the cost of letting art that might matter find us.

To find the work that matters -- whether in music or theater or on the computer screen -- you must trust yourself. You can't be looking around the theater to see whether everyone else is standing. You can't be watching who gets the grants and who got tenure, who published seventeen papers this year, whose book sold 864 copies in Detroit last week. If you’re hiring people or you’re on a tenure committee, you can’t just count citations and measure publications and you can’t run a popularity contest. If you’re thinking about voting, you shouldn’t care who is likely to win (unless you’re in the UK, of course, where tactical voting is a fact of life.)

You've simply got to trust your judgment.

My week of guest-blogging at The Atlantic has been great fun. A few posts remain in the pipeline, but if you only have time for one, the one to read is this: The New Reading. (The Atlantic gave is a new title, but I like mine.)

The series:

- Writing With Links

- Cheese Sandwiches

- Tech Support

- Art and Engineering

- A. I. (Don’t Hail Our Computer Overlords Just Yet)

- The New Reading

- Software Mistakes and Mistakes about Software

- Ovations

“I haven't been deconstructed like this in years.” – Lisa Cholodenko, High Art.

This, then, was the yeast on which Barad-Dur rose six centuries ago, that amazing city of alchemists and poets, mechanics and astronomers, philosophers and physicians, the heart of the only civilization in Middle Earth to bet on rational knowledge and bravely pitch its barely adolescent technology against ancient magic.

From Kirill Yeskov, The Last Ringbearer. I hadn’t heard of it before today, I’ve only just dipped into it. But I know Tolkien pretty well, and so far I’m not cringing.

Over at The Atlantic, Edward Goldstick observes that it's not good enough to protect computers against bad guys and bogeymen under the bed. The system is going to need to be turned off eventually, either because something breaks or something needs to be improved or someone has made a mistake. Planning for outages and interruptions can be as important as locking the door.

John Markoff’s piece about IBM’s Watson contrasts John McCarthy and Artificial Intelligence with Doug Engelbart and Intelligence Augmentation. This is an interesting and subtle argument.

The first conference event I co-chaired was the 1988 AAAI Workshop on AI and Hypertext. We opened with Ted Nelson on Xanadu: The One True System, and followed with Doug Lenat on Cyc: The One True Ontology. I looked at Cyc as a wonderful extension on hypertext – remember, in 1988 both Cyc and the Web seemed far, far in the future – but Lenat saw them as natural competitors. His concern, as I recall, was that if hypertext turned out to be good enough, it would set real machine understanding back for a generation while people tinkered with links and retrieval.

That’s pretty much what Watson does, as I understand it: it mines lots of hypertextual information to find likely answers, while not trying to build much representational depth. I haven’t read the papers; I may be wrong.

It would have been easy for Markoff, writing under the absurd headline “A Fight to Win the Future: Computers vs. Humans,” to make Engelbart the tool-building hero, giving people better tools instead of automating their jobs in opposition to the scary AI robot-builders. (Do androids dream of LED sheep?) But Markoff also captures the false-sounding note in the Augment doctrine:

Also that year the computer scientist Douglas Engelbart formed what would become the Augmentation Research Center to pursue a radically different goal — designing a computing system that would instead ‘bootstrap’ the human intelligence of small groups of scientists and engineers.

Small groups of scientists and engineers. That’s not unfair; I’ve heard Engelbart describe the idea in talks over two decades and more, and that what Doug sounds like. I’ve always winced. But take away the qualifying clause and we’re fine, the dream is intact, all is well. It might begin with a few people; not everyone learned to read at once, not everyone discovered painting at the same time. But I think most of us have always been working for everyone, not for small groups.

At the Atlantic, Timbuk2’s Lizzy Bennett likes asks, "Can Social Make Kids (Want to) Cook?" She’s finishing a week of fascinating posts about American manufacturing, and here ties Foodily – a social-software-enabled recipe aggregator – to her interest in Facebook and Twitter as a source of good ideas.

Foodily aggregates lots of recipes and makes it easy to vote for the ones you like. It’s a nice idea. But I think it’s probably hopeless. Because so many of their recipes, it seems, are drawn from link farms and SEO plays, you’re asking lots of people (some self-interested, some idiotic) to choose the best of a bad lot.

Take my first course last night: cream of broccoli soup. I made mine in what I believe to be the standard manner: make roux. sweat onions, add stock, simmer, add vegetable, purée, season with salt and lemon juice, add cream, crème fraiche, and garnish.

Now, what does Foodily suggest? 181 recipes! The first has no roux and is thickened with lots of cream and a ton of cheese. The second isn’t thickened at all. The third is plenty thick since it involves Velveeta, canned mushroom soup, milk, and frozen broccoli. A little further down we’re combining condensed milk, cream cheese, Velveeta, and more frozen broccoli. Another poaches the broccoli in bouillon powder.

There are three recipes for the Aviation cocktail. All three are wrong, omitting the crème de violette that give the Aviation is color and its name.

Consider picadillo: what chillis should we use? The top recipe suggests 1/2tsp of ground chipotle per pound of meat. Right pepper, but wrong form and far too little. The second has no pepper at all. The next calls for one twelth of a teaspoon of “hot sauce”. The next, 2T “chilli powder”. So we have to sort all the way down to the fifth recipe before anyone suggests that cooking some peppers would be a good place to start.

What’s going on here? We’ve got a bunch of sites like Cooks.com and AllRecipes.com that shovel thousands of “recipes” together. They game Google to land at the top of the search listings, which lets them sell ads. The advertisers don’t really care if the recipe is any good. Nor does the aggregator; as long as Google and Foodily send traffic, who cares if the recipe is any good?

Google is now nearly useless for recipes. I understand other consumer segments are nearly as bad. Social filtering like Foodily might in principle help, but only if the database begins at a point where good information can be found. There seems to be so much bad information in Foodily, I can’t imagine those social voters will stick around long enough to find the needles in their haystack.

Update: David Segal in New York Times has a good, if unremarkable, article about link farms. John Battelle points out that the culprit of the article, J. C. Penney, is a big Google advertiser, giving Google a good reason to look the other way. Everyone implausibly denies knowing anything about this link farming operation, and the Times, oddly, takes their word for it. Tim Bray picks out Segal’s best passage:

...the landscape of the Internet ... starts to seem like a city with a few familiar, well-kept buildings, surrounded by millions of hovels kept upright for no purpose other than the ads that are painted on their walls.

In The New Yorker, Adam Gopnick surveys a host of books about the impact of the internet. Of Carr’s much-publicized The Shallows, Gopnick writes

Similarly, Nicholas Carr cites Martin Heidegger for having seen, in the mid-fifties, that new technologies would break the meditational space on which Western wisdoms depend. Since Heidegger had not long before walked straight out of his own meditational space into the arms of the Nazis, it’s hard to have much nostalgia for this version of the past.

On the "fragmented, multi-part shimmering around us, unstable and impossible to fix" that Web surfing supposedly evokes, Gopnick observes sensibly that

This complaint, though deeply felt by our contemporary Better-Nevers, is identical to Baudelaire’s perception about modern Paris in 1855, or Walter Benjamin’s about Berlin in 1930, or Marshall McLuhan’s in the face of three-channel television (and Canadian television, at that) in 1965. When department stores had Christmas windows with clockwork puppets, the world was going to pieces; when the city streets were filled with horse-drawn carriages running by bright-colored posters, you could no longer tell the real from the simulated; when people were listening to shellac 78s and looking at color newspaper supplements, the world had become a kaleidoscope of disassociated imagery; and when the broadcast air was filled with droning black-and-white images of men in suits reading news, all of life had become indistinguishable from your fantasies of it. It was Marx, not Steve Jobs, who said that the character of modern life is that everything falls apart.

Yep.

Once more quote, because reading Gopnick’s review is so much fun. Gopnick warns that, just because there’s some precedent for the modern condition, we can’t be certain that the Internet isn’t the real disaster:

“Oh, they always say that about the barbarians, but every generation has its barbarians, and every generation assimilates them,” one Roman reassured another when the Vandals were at the gates, and next thing you knew there wasn’t a hot bath or a good book for another thousand years.

by Dan Cederholm

Available from the publisher, this compendium expands on Cederholm’s case for early adoption of new CSS features in contexts where their absence will not render the page unusable. This is a very good idea, simultaneously simplifying new designs and promoting faster adoption of Web standards.

Next week, I’ll be guest blogging at The Atlantic, while James Fallows finishes his next book.

One of the past week’s crew of Fallows stand-ins has been Ella Chou, a Harvard graduate student who grew up in Hangzhou. She pointed out this extraordinary advertisement for a Chinese instant messenger service. Watch it.

The craft and pacing of this ad are extraordinary, especially the acting of the mother, who conveys confusion and a degree of technical ineptitude without every becoming a buffoon.

My guess is that in China, where this ran as a very high-profile ad for the Spring Festival, the ad may read as merely sentimental. Across oceans and cultures, it’s moving. Sentimental art, removed from its context, can work remarkably well.

This video of sand-animation artist Kseniya Simonova might, to Russian eyes, read like a Hallmark card, like Thomas Kincaid. It sure intrigues me, though I don’t understand the iconography. What does the candle mean?

If you cook, you need a knife. You only need one knife, really. Kitchen stores want to sell you entire sets of knives – chef’s knife, paring knife, boning knife, bread knife. These can be useful, but if you’re not fluting mushrooms or boning quail, you need your chef’s knife. But because you're going to depend on your one knife a lot – and because knives present inherent dangers – you want your one knife to be a good knife.

What do we mean by “a good knife?” Some people might think this means “a really big knife”. My wife has a giant Sabatier that was a lovely gift, but it’s far to big for me to use, and ludicrously oversize for Linda. I think knife enthusiasts sometimes think that a good knife is one that looks great, a knife with a nifty finish and a wonderful handle.

But what we really want is a knife that’s sharp, well balanced, and easy to maintain. A good knife is a knife that cuts what you want to cut.

Hardware and software are like kitchen knives. Great materials and interesting shapes help draw attention in the store. They might be pleasant to look upon. Durability and economy are nice things, too. But what matters is cutting and chopping.

The iPad is a knife that’s both exceptionally attractive and exceptionally good. The pretty handle helps get people to notice it, and that’s not irrelevant to its success. The press and much of the industry seems to think that the iPad is a success because it is so beautifully polished. That’s a mistake.

The Kindle, for example, has never been well polished. It’s frankly ugly. It does one job: it lets you buy books right away. It’s a job worth doing. And so, people love it – not because the “experience” is right in every detail, but because it lets them read what they want to read.

by Mary Beard

A readable and entertaining overview of our current state of knowledge about Pompeii, one of the the Roman towns buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79A.D. Beard does a particularly fine job of explaining to non-specialists how our views have changed as we have learned more about Pompeii and as our interests and attitudes have changed over time. This is a fine history of History, then, but the focus remains on our surprisingly-detailed knowledge of this Roman town, and the even more surprising gaps in our knowledge.

Everyone is learning the wrong lesson from the smartphone wars.

The most recent entertainment in the ongoing competition to put a computer in every pocket is a controversial memo from Nokia CEO Stephen Elop that details Nokia’s shortcomings. John Gruber has the overview.

The first iPhone shipped in 2007, and we still don’t have a product that is close to their experience. Android came on the scene just over 2 years ago, and this week they took our leadership position in smartphone volumes. Unbelievable.

Gruber correctly observes that Nokia’s problem – everyone’s problem playing catch-up with the iPhone and iPad, is incoherence. People see the iPad selling. They copy the most obvious things – the touchscreen, the rounded corners, the black frame with silver trim. They add some software and stuff.

That doesn’t work. "Touchscreen, check. App store, check." Gruber writes. " Gaming, check. The trend Nokia missed out on? Kick-ass production values, quality, and experience." In an age where most of the “technical press” thinks that Apple’s advantage is some special design sauce that Steve Jobs personally sprinkles on new products, Gruber’s got his eye on the right ball.

But he’s wrong.

The iPad isn’t a success because the build quality is good, or because the animations are polished until they shine. The iPad succeeds because it lets people do stuff they need to do, and lets them make stuff they want to make.

All the polishing and shining helps get you to stop and look; what makes the deal is utility. Usability gets you in the door, but utility is what makes the sale, and what gets people to come back. The build quality is nice, but look around and you see lots of people with beat-up iPods and laptops and iPhones. They don’t have build quality, not any more. I know a university professor who travels around the world lecturing, and in his pocket he’s got an iPhone with a cracked screen. Not a great experience, not since he dropped it on the Paris pavement, but it still works and he’s got work to do.

It’s nice to make pretty things, but what really matters are the things that let us get stuff done.

In the current issue of The Atlantic, Brian Christian writes that

As computing technology in the 21st century moves increasingly toward mobile devices, we’ve seen the 1990s’ explosive growth in processor speed taper off.

That is probably wrong.

- In 1990, a Mac IIfx had 40MHz 68030.

- In 2000, a PowerMac G4 had a 500MHz G4.

- In 2010, a Mac Pro has eight Nehalem cores, each about 3GHz. Plus a graphic processor that’s much more powerful on its own than that G4.

We’re getting close, but Moore’s Law hasn’t been repealed yet. Perhaps we care more about mobile computing now, perhaps we don’t worry as much about processor speed. But that processor speed is there, and it’s still growing. All those nifty little animations that make the iPad seem so simple and pretty? That’s all about processing speed.

Where were the fact checkers, anyway?

Christian’s essay, which is mostly about the Loebner Prize (for chatbots that can come close to passing the Turing test), seems oddly concerned with gimmicks that programs can use to briefly mimic sapience. Yes, an argumentative chatbot (or a dilatory, absent-minded one) might keep an observer in doubt for a minute or two. That’s nice – and it might win you a prize – but that’s not the point.

If you can sit down with a computer and talk about stuff – whatever you like – for a reasonable time, and you can’t really be sure it’s not a person, then how can you know it’s not thinking? That’s Turing’s point, after all. We all agree that kids think; they might not be ideal dinner partners, but they aren’t rocks or forklifts. We all agree that, if rocks and forklifts think, they provide us no evidence of their inner life. That’s what the Turing test is about: when the forklift can give you the same evidence of thinking that leads you to believe that a kid or a taciturn stranger is sentient, then you’d best behave as if the forklift is sentient, too.

Taking a cue from Christian’s dismissive closing argument, if you can sit down and talk about stuff with a machine, and if you happen to like what it says, why can't you think of it as a friend? If what it says strikes you as inspiring and illuminating, why not consider it an artist? If you learn from it, why not regard it as a teacher? Christian seems to think that’s inherently absurd – and, for the simple-sounding chatbots he seems to have encountered, perhaps it is.

If you think it cannot possibly happen, it seems to me you’re a vitalist, assuming as a given then only some mystical soul can allow thought.

Oddly, though the article says it concerns artificial intelligence, none of the programs involved are described in any detail. We don’t know how they work or what they know. Most seem to be trying to exploit loopholes in the field rules, such as a 5-minute limit, that could entitle them to a prize even though they wouldn’t really be passing the Turing test.

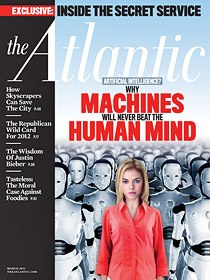

The cover headline,

Why MACHINES will never beat the HUMAN MIND

appears to have nothing at all to do with the article.

by David Mitchell

An expansive and delightful look at the opening of the 19th century, as experienced in the Dutch trade factory near Nagasaki. With great technical virtuosity, Mitchell takes this saga into genre territory -- the Ninja Raid, the Swashbuckling Sea Story – and then leads it out again. The massive book is obviously in dialogue with Clavell, whose excesses should not obscure his abilities, and with the incomparable O'Brian, but where O'Brian dissembles narrative sophistication, Mitchell exults in the spectacle, shifting mode and manner and point of view with ease.

Much Twittering today on the subject of teaching BASIC to beginning students of electronic literature.

In its defense, BASIC was important in the earliest days. Some of today’s professors of electronic literature got started with BASIC. Lots of them don’t program very much – they’re critics, not creators, or they use specialized environments like Flash or Avid that can’t easily (or affordably) be covered in an hour or two. And it makes sense that students learn something about programming.

I hadn’t laid eyes on BASIC in ages, though. It’s horrible. BASIC was meant to be FORTRAN IV with training wheels, and that was a great idea in its time, but nobody needs to build toward FORTRAN anymore – especially not students of literature.

We used to mourn the old days when programming languages were built into our computers and everybody learned to program. But – look! Your Macintosh comes with Perl and Ruby and Python built in, right out of the box. I’m sure you could get Squeak or Scheme set up in minutes. But the obvious language for the task, it seems to me, is Processing – and that’s just a download away.

Football is over – perhaps concluded for a bit longer than usual, thanks to the NFL’s earnest desire to reduce salaries.

Baseball is still far away. The ground is covered in snow and ice, and the equipment truck is still parked near Fenway, being packed for its annual voyage to warmer climes.

I used to call this, the season when software gets written, the season free from late-night and weekend distractions. I never code, nowadays, to the cheerful racket of noisy crowds, and I seldom code late at night.

Still, it’s time to polish up the next Tinderbox release, and to get moving on some nifty new things for the iPad. A weekend flood in my office led me to sort through my reading pile, and even after sending many volumes to the office shelf, I’ve got my work cut out.

And there’s a lot of writing needing to be done. So bring on the season of dark nights and midnight oil; it’s time to get cracking.

by Peter Straub

At Readercon, Straub spent the better part of an hour describing the difficult path toward creating this fine new novel, a struggle with old editors and new to publish a book that’s quite unlike his famous Ghost Story. The narrator’s voice in A Dark Matter is precisely Straub’s own, a feat writers seldom achieve even in autobiography, and he captures the contemporary midwest beautifully.

I don’t care for tales of the supernatural: I'm happy with magic as metaphor, yes, or magic as fantasy, but if what you’re selling is teasing apart the fibres of reality to peer at underlying, mystic truth, then I guess I’m a tough customer. But it is what it is, it’s superbly done, and it has characters and scene that I’ll remember for a long time.

by John Hart

Winner of the 2010 Edgar Award for best novel, this seems a surprising selection. My impression has been that Edgar nominees and winners are mysteries with terrific sense of place, or that they have astonishingly interesting characters. I may have lost track of trends; I seem to have missed most of the Edgar winners lately and the novel’s of which I am thinking are now twenty years old.

This is an entertaining book and it will, in due course, make a nifty movie, but it has neither. It’s a dual-protagonist mystery – a detective and a kid – and everyone behaves as you'd expect. The Police Chief does what Police Chiefs will do in books where the Chief's interest is not aligned with our those of the detective. So does the sheriff. It’s a mid-Atlantic story, so there’s a Big and Scary Negro of whom we ought not to be frightened. Everyone, in fact, is scary and unpleasant in predictable ways. The best character, probably, is the Kid’s Sidekick, who has a bad arm and a wry sense of humor.

Lots of intricately-plotted mysteries collapse at the end, but that’s when this book really gets rolling. There’s a lot of plot to be put into place, and once all the pieces are on the board, the machine rolls along beautifully.

Sometimes, “never apologize” really is the right answer.

BitchMedia published a list of 100 Young Adult Books For The Feminist Reader. Naturally, the list inspired discussion. That’s why sites publish these lists – they get lots of people talking, attract lots of inbound links, and so your advertisers sell lots of feminist sex toys and handmade winter bike hats.

Inevitably, some people thought some books on the list weren’t very good. Some felt strongly. Some wrote stern letters.

At this point, the wheels fell off: the editors read these comments, and found some of them convincing. So, they amended the list, dropping three books and replacing them.

Sarah Wendell has a good overview of the ensuing furor. Once the editors changed their mind of these books, they were defenseless. They tried to defend themselves by saying, “we didn’t read every book,” but that’s obviously doomed – especially in a community of writers and librarians. They tried to explain that there were cogent political objections to each book. That’s doomed, too. These books aren’t party platforms, they’re books for kids. The editors say, the replacements are good, too, and we’re not actually censoring anyone, and the books we dropped are still in our library in Oregon. I don’t see any way such arguments can convince anyone.

Margo Lanagan argues convincingly (and with surprising tact) that the indictment of her Tender Morsels is misplaced.

De gustibus non disputandum. It’s one thing to draw up a list of 100 book that omits one’s own work; that’s disappointing, of course, but there are lots of books. Weaseling, on the other hand, suggests that this really is a political process, and that the only way to defend your favorite work is to apply pressure to the editors. This gets lots of comments and lots of twittering – three pages of comments about children’s library curation! – and probably makes the sponsors happy. But it’s bad for libraries, worse for librarians, and terribly dangerous for literature.

- If you publish a list of favorites, stick to your guns. There’s no percentage in changing your mind.

- If you publish a list of favorites, be prepared to defend each one.

- Comments destroy weblogs.

- If you must have comments, don’t read them unless you have enormous patience, infinite reserves of tolerance, and an impenetrably thick skin. (Roger Ebert can have comments; mere mortals should not.)

An editor for Dalkey Archive’s Best European Fiction 2011 seems to have decided to improve Mima Simić’s story, “My Girlfriend”. Simić is very unhappy about the changes, especially one that establishes the narrator as male when the author had taken great pains to keep the narrator’s gender ambiguous.

I don’t write straight stories; and I don’t want anyone to be straightening my stories, in any way, sexual or textual—and certainly not without my consent.

A surprising train wreck, all the more remarkable because Dalkey, usually Web savvy and sensitive, seems slow to get off the dime on the question. The changes can be interpreted as political, though a more charitable (and, I suspect, more probable) interpretation might be that a junior editor or intern got carried away or didn’t think things through. In that case, Dalkey’s editors wouldn’t want to leave the intern on the clothesline, but a blanket “OMG what were we thinking?” would help.

There’s also the possibility of “gremlins ate my file”; no one meant to make changes, but changes were made. Things happen. You open a file one evening, you say to yourself, “I could make this better,” you take a shot, and you realize you were wrong. You quit – and you never noticed that you hit “save”.

Or, you get the letter from the outraged author. “I didn’t touch it!” you say to yourself. “Heads will roll!” You ask everyone, but no one touched the story. No one can figure out how the change happened. Small presses are busy places, nobody has enough time, nobody has enough computers. And of course the backups are inconclusive, and fresh deadlines loom. In the old days, you’d Blame The Compositors. Now, I think it’s the fault of the office pixies

.