Oliver Reichenstein of Information Architects (Japan) has an interesting discussion of a longstanding hypertext controversy: the conflict between the card sharks and the scrollers.

Unfortunately, he gets the history completely wrong.

Reichenstein’s belief that the people at Hypertext '87 were “neckbeards” is offensive. His account seems to rely entirely on the young Jakob Nielsen’s trip report; is Nielsen, that courtly Dane, a neckbeard? Doug Engelbart? Frank Halasz? Janet Walker? Randy Trigg? On this, Reichenstein has no idea what he’s talking about, he’s just making stuff up.

Reichenstein thinks the scrollers won because “99% of all websites scroll.” That’s dandy (if true — has anyone measured?), but it’s not the question at hand. What people were debating was whether following a link should take you to a new page — a “card” — or whether it should extend the text of the page you’re looking at right now. Nowadays, we call this stretchtext. You see it in weblogs that expand “There’s more…” in place, and you see it in exotic hypertexts for the Web.

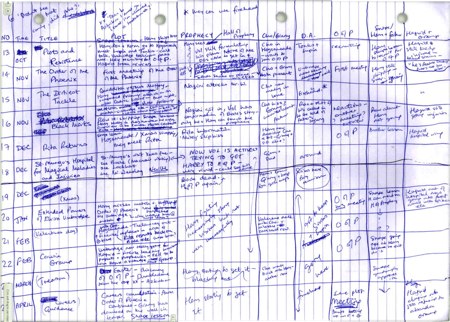

In 1987, many people thought the natural interpretation of clicking a link would be to expand the text in place. Peter J. Brown (University of Kent) had shipped GUIDE, a stretchtext system early that year, the first commercial hypertext tool for personal computers. Several other systems — Akscyn’s KMS (the US Navy was a big client) and Apple’s HyperCard – were pure card metaphor systems without provision for scrolling. Other tools, like Brown’s Intermedia, Bolter and Joyce’s Storyspace, Xerox PARC’s NoteCards, and Eastgate’s Hypergate, might scroll within the page but links took you to a new page.

People used to worry that card metaphor systems (like the Web) would disorient readers. I gave lots of talks back then on the subject of The Craft Of Hypertext, and my recommendations were exactly opposite from Reichenstein. Card metaphor is ideal for highly nonlinear presentation, where the hypertext map is complex; that’s why I used it in The Election of 1912. Stretchtext naturally lends itself to annotative hypertext a nearly linear reading. That’s why people lost interest in stretchtext well before the Web appeared. At Hypertext 2009, I wrote a paper On Hypertext Narrative that explained for the first time precisely why stretchtext scrolling proved so limited, and how this can be fixed.

A further issue in scrolling vs. card metaphor is latency – the time delay that accompanies link following. The personal computers of 1987 couldn’t do much page layout — running text around a float was considered a spectacular accomplishment — and many of these systems were running from floppy disks with seek times as long as your arm. The time needed to retrieve and format a new page could interminable. Brown University students used to bring a book to the computer lab so they could read while following a link, and on the USS Carl Vinson, sailors sometimes forgot what they had clicked before the new page appeared. Stretchtext, with simpler updating needs, seemed to promise a more responsive experience, making it easier to meet the requirement of Akscyn’s rule, that link traversal take about 250msec. (Ironically, we now live with Web latency much longer than Akscyn’s rule permits. But we don’t like it.) And since stretchtext preserves context, if you forgot what you clicked you can simply look and see it.

So yes: the appropriate role of scrolling in hypertext is still not well understood, and the nature of link traversal is still open to exploration. But getting the history right is always desirable. They weren’t neckbeards, and even back in 1987 they were researching a more complex and important question than simply eliminating the scrollbar.