A nice note in Wireframes on ways to convey emphasis in sketches. The same techniques apply in Tinderbox maps and finished Web pages, of course.

Kevin Eats ate at Alinea just a few days before we did, and offers wonderful descriptions and photography.

Near the end of the tour, our dinner at Alinea had a standard from Escoffier: pigeonneau a la Saint Clair. The course has been controversial; why include a staid 19th century showpiece in the middle of this wonderful postmodern feast? Achatz himself explains part of the point, but I think he is simplifying the thought.

What is this course saying?

First, what is pigeonneau a la Saint Clair?

With the meat of the legs prepare a mousseline forcemeat, and, with the latter, make some quenelles the size of small olives, and set them to poach. Poële the breasts, without coloration, on a thick litter of sliced onions, and keep them underdone. Add a little velouté to the onions; rub them through a tamis, and put the quenelles in this sauce.

In the middle of a shallow croustade, set a pyramid of cèpes tossed in butter, Raise the fillets; skin them, and set the on the cèpes; coat them with the prepared sauce; surround with a thread of meat glaze, and plant the quenelles all around.

OK: that’s the instructions. Why do we do this? It’s not just hoops to dance through, or an arbitrary set of rules or customs.

First: why pigeonneau – squab? At this point, we want some poultry to set off the steak and potatoes. Squab makes sense; we want a taste, not a turkey. This is a perfect time for a small bird: it’s a big menu.

But how do we approach the problem of cooking a whole bird perfectly, when the whole bird is so small? This is always the problem with poultry; the breasts are overcooked before the legs are done. Besides, legs are hard to carve, so squab is famously hard to eat. (The last time I had squab was at a wedding; that was just a little bit hostile!)

No problem: we’ll carve up the bird and prepare the parts separately in order to get each morsel right. We bone out the legs in the kitchen (where we have sharp tools and aprons), and mince them up to get rid of the toughness. We mix them with egg and cream to make an emulsion, and poach these little balls of squab sausage.

For the breasts, we want to season them gently and cook them very gently. If you have a great big chicken breast and the outside is just a little bit overdone for texture, it's no problem; make it a tiny squab breast, and a thin layer of overcooked meat adds up to the whole thing. So we cook it gently, gently, on a bed (a litter!) of onions. And then we mustn’t waste those lovely onions, bathed as they are in meaty juices, so we add a little bit more stock and turn them into a sauce. Add some mushrooms, since they go well with poultry. Serve in a shallow pastry bowl, which brings everything together, absorbs the delicious juices, and gives us another texture to experience and another place to vary the flavor.

So: it’s not arbitrary or fusty. It’s a solution to an old cooking problem.

It’s also a ridiculous amount of work. But we’re not being convenient here, we’re throwing everything to the winds to make the dish exactly right.

Now, lots of Alinea addresses the same sort of problem, using different means. Take that truffle explosion: a raviolo, topped with a slice of black truffle, and filled to bursting with black truffle juice. The idea is, simply, to have a burst of pure truffle flavor. But you can’t just do it, because you can’t fill ravioli with truffle juice, because the liquid will just run out on your counter. So we start working with gels and reductions, and we start reimagining tableware because we need to get that one perfect truffle raviolo to you without breakage or leakage and while it’s the perfect temperature.

This is a good way to cook a squab, just as the wagyu short ribs (perfectly rectangular, meltingly tender pieces of short rib on a Guinness gelatin sheet) are a perfect way to cook short ribs. The course is an argument that what Achatz does is not a repudiation of traditional cooking (as nouvelle was), but simply expands its horizons.

My cousin has a “permanent” email address through her college. But, as it turns out, the college got tired of email hosting, so they’re not going to do that any more and plan a new Web 2.0 social web service instead. This is nice and shiny, except that my cousin actually counted on the permanent email address being, well, permanent.

I expect this will be a more common problem as we renegotiate responsibilities for Web services. And I think there’s a long-term problem with domains and naming; I can imagine a dystopia where domain ownership becomes a sort of hereditary nobility.

Twenty four hours later, I’m still assimilating impressions from dinner at Alinea. They remain less than coherent; in fact, it has been a dizzying experience. I’m going to start with incoherent notes and snippets; I’ll write about some of what seemed to me to be key ideas and key dishes once I’ve had a little more time to reflect. (Three days later: still dizzy — MB)

- This was the best meal I’ve ever had. (25th anniversary dinner; it ought to be the best.) All-time food list, barring things I've forgotten at the moment:

- Alinea

- the Thai fish lunch

- Les Bouquinistes III

- No. 9 Park

- Beach dinner, Rio Negro, near Manaus

- Topolobampo I

- Da Ilia, Milano

- Dorchester Grill New Year’s, London

- back room of some place, Firenze

- crawfish after the opera, Goteborg

- The Holiday Inn Fried Chicken Feast, somewhere in Alabama, c. 1962

- L'Espadon Bleu

- DOC bar

- Roman fish lunch (aka “my limoncello tree”)

- street souvlakia, somewhere in the Peloponnesus, 1964

- Geronimo, Santa Fe

- Amazing staff. Everyone busy, everyone working, nobody rushing, and nobody seeming to worry about their next task. This applies to both sides of the house (the magnificent, carpeted kitchen being partly visible from my chair) and despite adverse circumstances: I don’t know why a team of firemen with emergency gear appeared during dinner, or where they went, or what they did, but whatever went wrong, it was handled with calm and ease.

- Though I’d read a good deal about some of the signature dishes, each came as a delightful surprise. The truffle explosion was magnificent; for the first time, I think I understand the fuss about truffles. The frozen poached grape on the antenna sculpture — it works. The powdered essence of A-1 — it works. Many things that sound precious or silly when you read about them, actually work.

- The bread changes several times through the meal, often to play off a course. Two courses featured crab, duck confit, and peas; the bread was a cookie flavored with Old Bay. There was a wonderful little tea-infused bagel. There was a wonderful “plain dinner roll”, which just happened to be fresh from the oven – not, I think, reheated – at midnight.This is very well thought through, and now I wonder why more places don’t do more with bread. The ingredients aren’t costly, the work is mostly prep, little needs to be done at service, and if something goes wrong you know about it and can substitute.

- 25 courses is a lot. It was precisely the maximum amount of food I could enjoy. (A course per year is poetic, too.) Someone worked this out, with both hands. Everything has been worked out, with both hands, and without compromises.

- Magnificent wine, brilliant pairings. Takasago Ginga Shizuku Divine Droplets with the incredibly complex white asparagus and sorrel. The best pinot gris I’ve ever imagined, much less tasted, with crab and duck confit #1. (I can imagine good, but this is pinot gris, and this was good) The best spätlese I’ve ever had, with foie gras — an old spätlese, it was explained to us, so the sweetness folded in on itself. Face it: a wine pariting for “pork belly, iceberg, cucumber, and Thai distillation” is going to be a challenge. I didn’t follow every line of the proof, but I appreciate the moves.

- Late in the tour, pigeonneau a la Saint-Clair, right out of Escoffier, with a Chateaux Lascombes Margaux 2004. This course has been controversial. I think I understand part of its argument, and I’ll write about that later.

- Serving sweet potato pie on a cinnamon stick is clever. Serving it on a smoldering cinnamon stick is genius. Seriously. It sounds absurd, but it’s unforgettable. (And even more complex than it seemed)

- The informative, and helpful service avoids almost any talk about the wonderful ingredients or complex preparations. Just what a dish is, and (often) how best to approach it. More information on the wine, which makes sense, but even then, all that was said about the claret was “I’m not going to say much about this one.” Again, this is nicely thought through: if you know wine, you’re going to know about seconds crus bordeaux, and if you don’t, taste it: you don’t need the spiel.

Summer is here, and Steve Ersinghaus and crew have started this year’s 100 Days Project. 100 Days of Hypertext, too.

Today we acknowledge how much we've forgotten by paying homage to what we have managed to remember.--David Kurtz

One highlight of Tinderbox Weekend London was Robert Brook’s discussion of using Tinderbox for planning public information programs for the British Parliament.

A key theme of his talk was the importance of sketches — small, quickly-prepared documents that hold the information you need yet remain malleable enough to adapt quickly as changes are required. “People often make oil paintings when they want sketches,” Brook observed.

For example, consider the meeting agenda prepared for a series of meetings with the varied stakeholders of a project. Instead of printing numerous agendas tailored for each different audience and constituency, a single Tinderbox agenda can let each meeting focus on its chief concerns through natural actions in hiding, showing, and arranging elements. Map views let participants see what they’re discussing and what is being passed over; people suddenly notice that this thing over here actually connects to the other group’s thing over there.

This flexibility extends from Web projects like Hansard, a new Web repository of Parliamentary debates from 1803 that was partially prototyped with Tinderbox, to performance reviews and management negotiations. In budget discussions, for example, it can be helpful to make note sizes proportional to cost, focusing attention on the most pertinent items.

My own notes for this fascinating session are something of a mess, highlighting Brook’s own observations of the importance of informal and even fuzzy tools. Keeping control and responsibility in one place, he insists, is key: being able to change the map within a presentation gives speakers a way to visibly incorporate changes and address objections that is indispensable where many interests must be satisfied and where changes will need to be accommodate and embraced throughout the entire development cycle.

Just saw Doubt. Any movie that pits Meryl Streep against Philip Seymour Hoffman is bound to be good. Really good.

In one scene, the school kids are singing carols.

Was to certain poor shepherds

In fields as they lay.

And this, for reasons I cannot fathom, has me scratching my head. What’s going on here? OK: there were shepherds abiding in the fields, and the angel of the Lord came upon them and the glory of the Lord shone round about them, and they were freaking out. Got it.

But is the carol saying that the angel appeared to certain poor shepherds, shepherds who were carefully chosen to meet determined criteria that need not concern us here? Or does the carol say that the angel appeared to the shepherds and reassured them, assuaging their doubts and fears and uncertainties? And if the latter, presumably the angel’s reassurance extends further than to their (sensible) concern that the angel itself had aroused? (Were the shepherds sitting over a campfire, worrying about tuition bills and health care reform?)

(Christine Robinson, a UU minister, has no doubt that the intended meaning is “particular.” But she doesn’t say how she knows this, and accepts as valid a young person’s critique that it seems paltry to single out only a few shepherds. There’s an inconclusive discussion at phrase finder. This page says it’s known to be 16th or 17th century but might be 13th.; I suspect “certain” is Victorian, in which case we can’t rely on the OED because it might well be Victorian emulation of Elizabethan usage; even if “certain” might be unlikely in 1599 (would it?), it’s not so wildly improbable that a random Victorian editor would necessarily cast it out. On the other hand, I don’t believe Shakespeare actually uses certain as a transitive verb.)

My question about legal applications of Tinderbox garnered all sorts of interesting mail, from Vancouver the north woods of British Columbia to Kathmandu. Everything from teaching police officers to be better witnesses to mapping lines of influence in the Afghan resistance to the Soviet Union.

Forensic psychiatrist Dr. Fionnbar Lenihan writes from Edinburgh that he found Tinderbox "good for doing some quick pandemic flu planning." He’s the pandemic czar at his facility; closed communities like prisons are particularly worrisome for managing disease outbreaks.

Once I had sketched out some ideas on a map, I was able to print off a view and use that for discussions with other people.

This is an example of a “disposable Tinderbox” – a Tinderbox project that’s intended as a sketch or study rather than a long, ongoing project. Tinderbox serves its role in the early stages, where its flexibility and responsiveness help capture ideas without premature commitment to an organization or framework or conclusion. It’s easy, for example, to accommodate information in Tinderbox that “doesn’t seem to fit”, or ideas that might not fit with the expected result. Later, you can pick up and move to Keynote or InDesign or whatever you want to use for production; Tinderbox now serves as a storehouse of information from which you can draw.

I’d like to understand better the ways people are using Tinderbox in legal work— including thing like law school notes, police work, investigative reporting, litigation support, forensics, legal scholarship, and corrections. If you’re involved in any of these areas (or anything else pertinent), I’d love to hear from you — either post on the Tinderbox forum or Email me..

by Sarah Waters

The author of Fingersmith, Tipping The Velvet, and The Night Watch takes on a ghost story. We have a decaying family, once prominent and wealthy; indeed, the narrator’s mother was briefly a servant in their nursery. The narrator himself, a Dr. Faraday, has grown up to be a country doctor, though it’s 1947 or 1948, and he fears that the coming reorganization of British health care will destroy his tenuous practice. He is summoned to examine a housemaid – the last servant in the ruinous mansion – and by degrees is ensnared in the peculiar story of this most peculiar family and their strange, deteriorating house. Waters is always admirable, though her tales always unfold with stately, almost painful, gradualness.

Dave Winer is looking for pointers to “people who are active in technology, who also blog, whose integrity you trust.”

Occasionally, the “year ago” gizmo (bottom left corner of markBernstein.org) dredges up something useful that I had forgotten.

Today, it's “The Economic Motivation of Open Source Developers”, my take on Dirk Riehle’s optimistic essay. Riehle argues that open source, by driving down the price of software and increasing the interchangeability of developers, will benefit everybody. I was wary:

What Dirk fails to consider here is capital: who will ever build new software, or new software companies, if they can be so easily destroyed? The scenario demonstrates how open source can act as an agent of capital destruction; it's not clear what role it plays in renewing this resource.

....

The essay suggests that rational developers should rush to become committers to successful open source projects; once securely ensconced in that role, they can command a premium salary (even though they may no longer have time to do actual work for their employer!). But will this work? There can only be a few committers; this seems a recipe for building a software world with a few well-paid foremen (who don't actually do any work) and a lot of poorly-paid mechanics who spend their days writing production code and their nights struggling to please the foreman and aspiring to reach the airy heights of open source. This seems a recipe for recreating the worst aspects of the labor union, stripped of the notion (sometimes, arguably, a pretense) that the union represents its members. In this brave future, we’re all going to be Teamsters.

When I wrote this, the current depression was already under way. But we didn’t know that; at any rate, I didn’t know that. In today’s Boston Globe (and you never know these days whether tomorrow’s Boston Globe will be the last), there’s a story about a software engineer who, out of work for the better part of a year, has bought radio ads in the hope that some manager will hear about his expertise and hire him.

I fancy that he’s not telling prospective employers that he’ll be spending most of his time working on community software.

by Gordon Wood

Franklin was born a British subject, one who happened to live in Massachusetts. In his early middle age, he moved to London (which he loved) and became one of the leading theoreticians of the cause of Empire. Later, after a brief return to the colonies, he became the new Republic’s ambassador to France. The French adored the witty, exotic, and accomplished Dr. Franklin, and Franklin adored Paris. When he died, the French saw him as the model of the new age, and the Americans saw him as vaguely French. Nevertheless, he became the quintessential image of Americanness: democratic fairness, thrift, industry, science. Wood skillfully examines how the transformation happened, and how it served succeeding generations of Americans.

Not far from the Rookery, this mecca of head-to-tail cooking has a lively bar and a fun, white space with a semi-open kitchen. The menu wasn't nearly as full of oddities as I’d expected, but it was fun and seasonal. And there was a party who had ordered a whole pig in advance — that was pretty spectacular.

I had a cuttlefish appetizer – solid but unspectacular – and then a lovely slice of roast pork, served with the best dish of greens and butter beans I’ve ever tasted, sauced with a complex, balanced mustard that works brilliantly with the pork. It’s our old friend Sauce Robert, but it’s simple and unfussy and delicious. Dessert was a Bakewell tarte with a dollop of jersey cream. Terrific.

Followed up, later in the trip, by an even better dinner at Hix. Five varieties of oysters – with Chablis. Braised rabbit with wonderful little jersey royal potatoes – with a great Coteaux du Languedoc. And then a shipwrecked tart with a wonderful dessert wine.

When you come right down to it, there’s some really good food in London these days.

Tinderbox Weekend London was held at the Rookery, a lovely little hotel in Smithfields, which is still London’s central meat market. They've taken several old butcher shops and remodeled them into a nice combination of old and new. They have real books lying about on nearly every table – there’s a volume of Ruskin in the front hall, and the Library has lots of old bound volumes of Punch. As someone twittered, it was a bunch of fine 20th century people in a lovely 18th century building, talking about 21st century software.

I spoke about Tinderbox dashboards, timelines, and the Cookbook. Mark Anderson did a fine exploration of new developments in Tinderbox export. J. Nathan Matias has undertaken a thorough exploration of version control as it relates to Tinderbox: he has a paper coming up at Hypertext 2009 about the problems of spatial diffs. (Bottom line: version control of Tinderbox files is hard right now. I think I know how to make it easier. Stay tuned.)

Robert Brook talked about Tinderbox and Parliament. Spatial hypertext works great in meetings. In fact, it works so well that we need to step back and think more closely on exactly how and why it works.

And then Michael Bywater wowed us all with Plotting In Tinderbox. We didn’t manage to plot a novel, but many fine ideas were thoroughly tossed.

It was a fascinating group: academics, lawyers, a writer, IT pros, a psychiatrist. I had a great time. As usual, I learned lots.

I took the new, late flight to London, which makes it easier to sleep on the plane. A further advantage of the times is that the flight was half empty.

I spent most of the day in two 18th century houses that have become museums. Dr. Johnson’s Gough Square rental is a lovely, modest little place. It’s a little bit bigger and perhaps slightly grander than the Adams Homestead in Quincy, but not by much – and of course it’s in London and not in a suburb of a primitive colony.

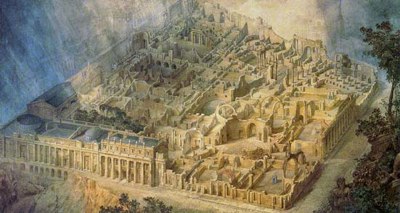

Sir John Soane was only about a generation later, but his house in an amazing museum. It was meant to be: he was a prominent architect, he designed his house to be a museum, and he arranged for Parliament to take it over and preserve the house just as he left it. It’s filled with amazing things: 4th century Apulian vases, a fine early ship’s chronometer built for the Duke of Marlborough, the Sultan’s pistol that Peter the Great captured, and then gave to Napoleon. There’s a Picture Room with the originals of Hogarth”s “Rake’s Progress” and a set of Piranesi sketches. There’s Gandy’s wonderful tribute to his friend, showing Soane’s then-new Bank Of England building as it might look in a thousand years or two, a carefully-preserved and studied ruin.

This painting was (and is) hung behind an ingenious hinged panel that is itself hung with other paintings, a fine if desperate expedient when one runs out of wall space. Knowing it had to be somewhere, I asked a guard where it might be. He graciously unhinged the wall to give me a peek.

Another great room is the first-floor drawing room, restored to its original hue of Turner’s Patent Yellow (lead oxychloride: think chrome yellow, maybe just a little cooler but just as saturated). It certainly is warm and inviting, though it must have cause the women some interesting pains in choosing what to wear.

It would be fun to do a monograph detailing the influence of Sir John Soane’s Museum on Isabella Stuart Gardner’s. She surely knew it, and I fancy I seem some quotations in the Gardner, like the sarcophagus in the central court. And I imagine the whole idea of the atrium is a response of another kind: we’re Americans, ours is a big country, we have space. Soane is all about ingeniously fitting his stuff into three townhouses; Gardner builds a new house around a wonderful indoor garden. The topic would make a fine little book. It probably already has.