Jean Goodwin launches a thread on Tinderbox and the Craft Of Scholarship with an intriguing quotation from Scott McLemee’s appreciation of C Wright Mills’ “On Intellectual Craftsmanship.”

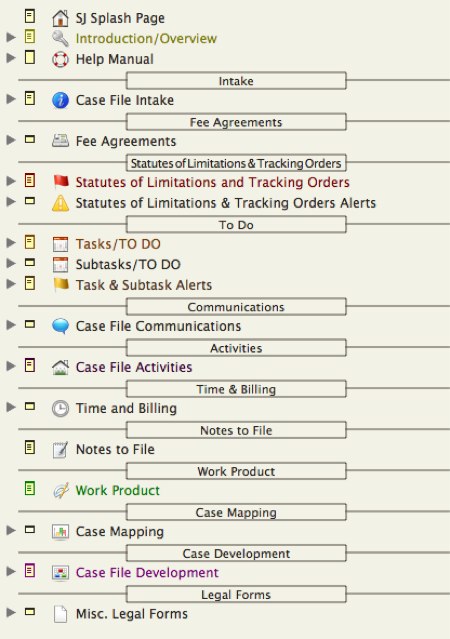

For Mills, there is a kind of bench where all of this crafting takes place. He calls it "the file."...

For one thing, [the file] includes reading notes and other such documents generated in the course of your research. But the file is also something like a journal. It's where you hammer out the coherence between the different projects that absorb you, and brainstorm new lines of inquiry. "In such a file," Mills writes, "there is joined personal experience and professional activities, studies under way and studies planned." It is where you hash out the complications in any given work-in-progress, and take notes on stray possibilities that might be worth exploring down the line.

One benefit of this is that it can help subdue, or at least reduce, anxiety over writing. (Mills suggests adding something to the file at least once a week.) And it "encourages you to capture 'fringe-thoughts': various ideas which may be by-products of everyday life, snatches of conversation overheard in the street, or, for that matter, dreams. Once noted, these may lead to more systematic thinking, as well as intellectual relevance to more directed experience."...

"You will have to acquire the habit of taking a large volume of notes from any worthwhile book you read," writes Mills, "although, I have to say, you may get better work out of yourself when you read really bad books."

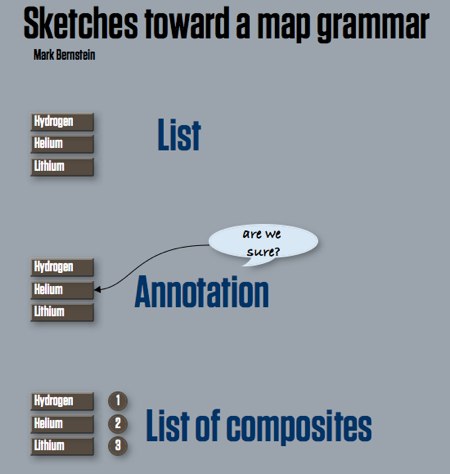

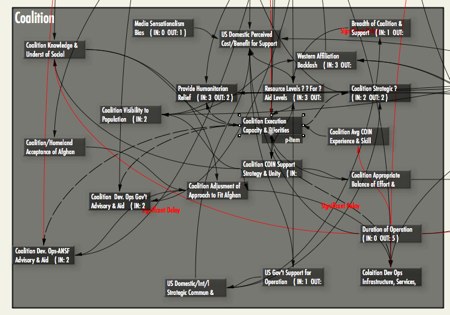

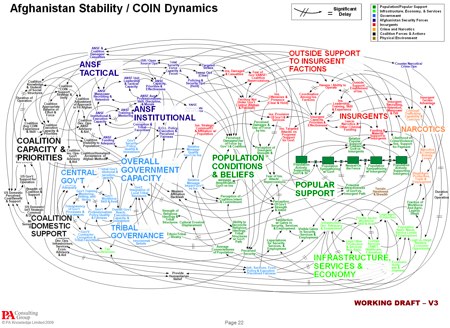

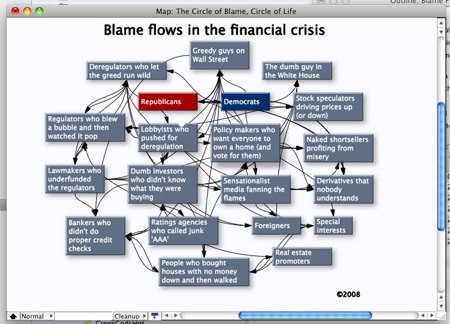

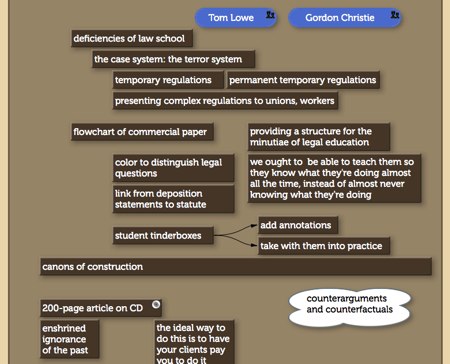

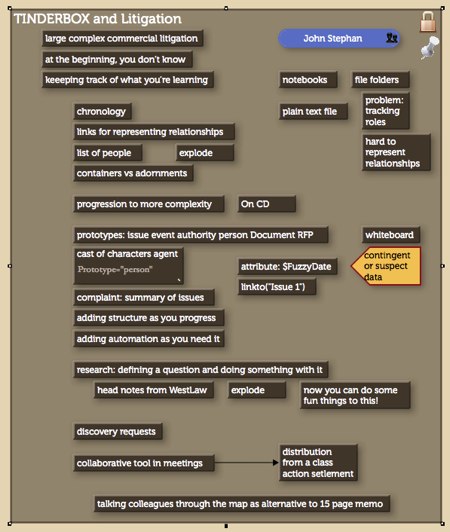

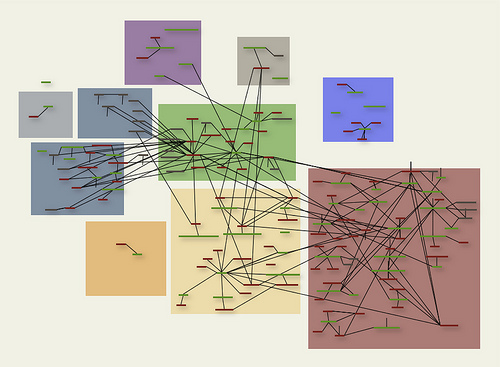

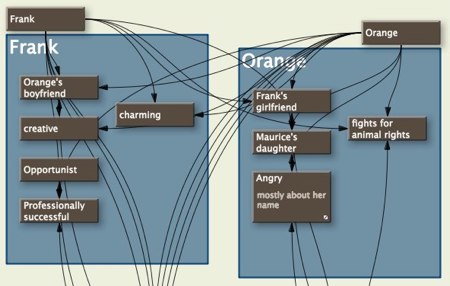

Apart from taking notes and drafting memoranda-to-yourself, Mills suggests that your files ought to include charts and diagrams. As a sociologist, he was used to presenting some of his findings in that format. But Mills's point is that the intellectual craftsman shouldn't wait until writing for publication to experiment with visual display. Tables, charts, and diagrams "are not only ways to display work already done," he writes; "they are very often genuine tools of production."