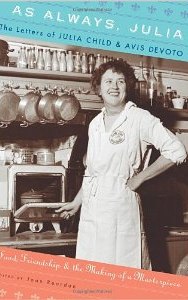

As Always, Julia

by Joan Reardon, ed.

In 1952, Julia Child read an article in Harpers about the shortcomings of stainless steel kitchen knives. She agreed wholeheartedly, and sent the author – public intellectual Bernard DeVoto – some inexpensive French knives. Her reply came not from the author but from his wife and secretary, Avis:

I hope you won’t mind hearing from me instead of from my husband. He is trying to clear the decks before leaving on a five weeks’ trip to the Coast and is swamped with work, though I assure you most appreciative of your letter and the fine little knife. Everything I say you may take as coming straight from him – on the subject of cutlery we are in complete agreement.

Bernard had indeed appreciated the gift, and had appropriated it for the cocktail hour. But Avis turned out to be a fine and lifelong correspondent, and because Avis had terrific contacts in publishing, this letter turned out to be a crucial step in securing the eventual publication of Mastering The Art of French Cooking.

Joan Reardon has collected much (but not all) of the surviving correspondence between this first contact and the publication of the book, some eight years later. It makes a fascinating record, not only of an intricate editorial process but also of the intellectual and political world of the 1950’s. The DeVotos were at the center of the Hub. The Schlessingers lived next door and came regularly for drinks. So did the Dean Rusks. Paul Brooks, Dorothy De Santillana and the Houghton Mifflin crew were close friends, May Sarton was down the street, Albert and Blanche Knopf were close as well. DeVoto, though not well known today, was a titan who was banqueted alongside Robert Frost and Sam Morisson, Bill Faulkner and Rachel Carson at a ceremony for the great writers of the century. Child, married to a State Department official, was posted far in the periphery, unknown and greatly in fear of McCarthyist witch-hunting.

There’s not much in Julia’s letters that we didn’t have in her own recollections and her biography. DeVoto, on the other hand, is a fine discovery and a terrific writer. There’s not much to learn here about cooking, but tons to discover about sexual politics and social life and household economy. I wish the footnotes gave us a little bit more background about people the letters mention – the footnotes are not the match of Charlotte Mosley’s – and I’d have gladly read some of the later correspondence, omitted here, from later years when the widowed Avid DeVoto became one of Child’s assistants. Still, these are delightful letters that brim with enthusiasm, spirit, and the patience to nurture a large and difficult creation.