Covent Garden Jugglers

Outside Covent Garden, we watched a very amusing and elaborate juggling act by two older men who did surprising things with balls, pins, unicycles, umbrellas, and a six-year-old girl named Olivia.

It was interesting to watch them shape their space, urging some people to come closer, others to back off, making jokes at the expense of pedestrians who walked across or through that part of the pavement on which they defined their invisible stage. This has, of course, a utilitarian component: when you're juggling on unicycles while retying your bow tie, you don’t want some bystander stumbling into your path with an armful of art glass and meringues. But at the same time, pulling people closer (but not too close) knits the crowd’s experience together and makes them more alert and engaged.

At Tinderbox Weekend, Michael Bywater made some very interesting observations about maintaining this balance. He is currently working on a musical, and he explained that one wants the dramatic tension to increase gradually through the course of the first act, and then again to increase through much of the second act. In addition, though, local tensions increase in each scene until the characters can no longer speak, and the challenge is to extend this tension as long as possible until the characters must burst into song.

My copious notes of Bywater’s talk were made by iPad. I had exhausted the laptop’s battery, and so Tinderbox was, briefly, not an option.

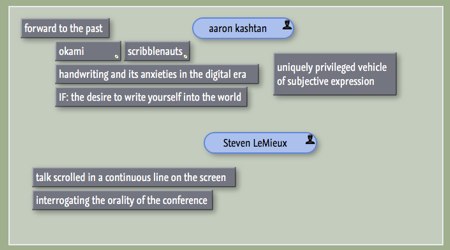

The notes frequently burst into song, or at least into nonsense. One reason is that I’ve become used to being able to make notes is multiple streams. Here’s a small example from a conference earlier this year:

Reviewing a long list of text notes, I’m finding it hard to sort out which of my notes follow or extend the previous notes, and which introduce an entirely new topic. Simple layout lets me add a quick clue to this without taking any time, or giving the matter any particular thought.

Also interesting was the sheer number of implementation details that must be considered in the book of a musical or the screenplay of a film, and how small changes can resolve complication and expense if the issues are foreseen.

Bywater opened with an example – a stage direction in a screenplay. He’d written,

Steam rises from a treacle pudding.

Production costed this shot at $12,000. You need a cook to prepare the pudding, a gaffer to light it, an electrician to take care of the cookstove, a props man to carry the pudding to the set, a teamster (who knows why), and lots of things I’ve forgotten.

On further review, the same effect can sometimes be achieved by having the actor complain that there’s no damn pudding.

When we planned Tinderbox, we didn’t specify that it ought to keep track of the number of costume changes you’re requiring the members of your chorus to undergo . But it’s nice to know we can do it.