Should Hypertext Fiction Be Rated?

A sermon about The Children

I had an interesting exchange this morning with Andy Campbell, the accomplished artist behind DreamingMethods.com. He is developing a digital fiction "Changed" for the iPad, based on a script by Lynda Williams, and notes that

In contrast to the influx of 'child picturebook' releases offered by publishers on the iPad, this work will be rated 15 for its adult content and theme.

On the same morning, many voices were calling for Amazon to ban a book about pedophilia.

Aren’t these simple common-sense positions that protect children?

My grandmother had a first edition of Lady Chatterly’s Lover. To read Lady Chatterly when it was new, you simply needed to know someone who was going it Italy and would bring you a copy.

This meant, in effect, that every American could read Lawrence, provided they were rich or knew someone who was. The same thing was true about birth control.

There is a great deal of ignorance in the world. We should not add to it.

Norman Mailer came back from the war, determined to write the real story, not Hollywood lies. He wrote The Naked And The Dead

, a book in which soldiers talk the way soldiers actually talked, and do things that soldiers actually did. This made sense, because a few million of his readers had, like Mailer, recently been soldiers and knew perfectly well how soldiers talked. But you couldn’t put that on the page, not in 1948, and so Mailer’s book reads like this:

The Jew had been having a lot of goddam luck, and suddenly his bitterness changed into rage, constricted in his throat, and came out in a passage of dull throbbing profanity. “All right, all right,” he said, “how about giving the goddam cards a break. Let’s stop shuffling the fuggers and start playing.”

“Pretting fuggin funny,” Gallagher muttered half to himself.

Admittedly, this set up one of the great meetings of all time: when Dorothy Parker was introduced to the young Mailer, she quipped, “So you’re the man who can’t spell ‘fuck.’” Still, the subterfuge permanently defaces Mailer’s best novel. (It is worse, of course, is that Mailer had to be so elliptical about homosexuality that the modern reader can easily miss the crisis that drives the whole story. But the prissy fuggery is bad enough.)

Now, all this might be tolerable if, in fact, Mailer was conflicted – if he couldn’t bear to say fuck or to think about what a lonely general on that fugging island might want to do with his favorite lieutenant. But if that’s the Norman Mailer you believe in, I have a nice bridge in Brooklyn just for you.

The effect of worrying about this stuff – fussing over the fact that people have parts and sometimes use them – distorts publishing, criticism, and writing. The impact on artists is unknowable but severe. To Have and Have Not

(1937) may well be Hemingway’s worst book, but surely part of the problem is that Hemingway was trying (in part) to write about a perversely self-centered and selfish woman and, in setting up a really ugly and unpleasant sex scene in which nothing at all can actually be described, Hemingway ends up with so much bitterness spilling around that the finale gets whacked out of shape. Hemingway is trying to do Molly Bloom for some ghastly value of Bloom, but he ends up at sea with Harry Morgan, and taste is left bobbing around in the ocean, waving for help.

The same novel cleaned up just fine to make a wonderful movie

. Howard Hawks can’t think about showing what Hemingway couldn’t describe, so the whole unpleasant character goes out the window. In her place, we get Lauren Bacall. I haven’t worked out the dates, but if Bacall was 18 when they shot the film it was a close-run thing. Today, you probably couldn’t have cast her, and Zeffirelli definitely couldn’t have used Olivia Hussey as his Juliet.

And maybe you think that’s all fine, and we can throw this art away to protect the kids. Besides, it’s a voluntary rating system, right?

I sympathize with the people who want warning labels. I’ve used them here at Eastgate, once or twice, at the request of authors.

But three generations of talented writers worked tirelessly for the right to write what we say and do every day, not what some self-appointed preacher tells us is safe for kids. When we “voluntarily” rate artwork, we inevitably suggest that those aspects we call out are in some way suspect. If we want to cast suspicion, the right place to do so is within the work itself. Otherwise, we betray not only our own work, but the sacrifices of generations who fought for our right to write – and we make it harder for other artists to say what must be said.

Lots of people think that homosexuality is bad for kids. What are you going to do when they ask you to “voluntarily” label It Gets Better for 18+? Lots of people think that birth control is bad for kids – or, indeed, for everyone. An entire political party (and its television network) thinks Islam is wrong. A big party of that party thinks that evolutionary biology should be rated 18+.

Theaters now have signage to warn the audience that loud noises will be part of the performance, or that characters in the play will smoke, or that there will be flashing lights. This is not unreasonable, since a few people experience extreme discomfort from sudden noise or smoke or flashing lights. I think it would be preferable, however, to post a stock notice for all performances:

Some performances in this theater involve strobe light, smoke, and/or loud or sudden noises. If you are concerned, please consult the box office for details of this performance. No photography or recording is permitted.

This would avoid revealing that someone is going to be shot in Act III when that ought to be a surprise, while people with epilepsy can get needed information easily enough.

What, precisely, is gained by trying to prevent children under the age of 12 or 15 or whatever from hearing certain words? Especially when these are words in which, it seems to me, children chiefly delight?

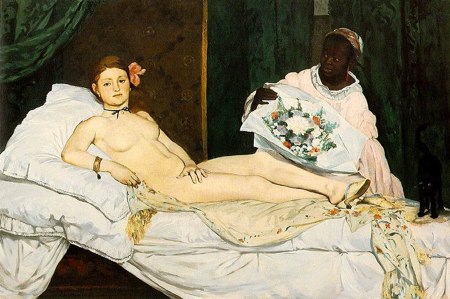

The impact of simulation has always been important to art, and it always complicates the erotic in art. Olympia was controversial not because she was undressed, but because she didn’t see to care.

It was fine to show naked women being spied upon, surprised in the bath, tormented by slavers, or executed by heathens; these were familiar subjects. Showing a woman who was comfortable and in control was deplorable. Art galleries that post warning signs to alert visitors that an exhibit contains nudity are aiding those who would love to reproduce that forgotten time when women knew their place.

I once took a phone call from a teacher at a Catholic school in New York who wanted to teach hypertext fiction but was fearful of objectionable content that might cost him his job. We spent a considerable time discussing the woodcuts in Patchwork Girl and the iconography in afternoon. Only after we hung up the phone did it occur to me that the naked drawing of Patchwork Girl is in fact an allusion to medieval (and Victorian) martyrdoms. The priest and the publisher had just spend a half an hour discussing whether Catholic high school should be exposed to an image that might not be very out of place on a 12th century icon.

We were so concerned with the question of breasts that neither of us spared a thought for the saint. Here endeth the lesson.