I’m speaking this week at Presidency University in Kolkata, about NeoVictorian computing and the digital humanities. We’ve made lots of progress in the digital humanities in the last thirty years; already, we can see the time when they’ll just be the humanities. The important discoveries may come from a direction most people don’t expect.

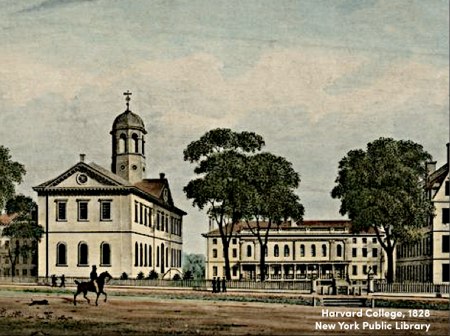

The ancestor of Presidency was founded around 1818. I studied at Harvard. Here’s what Harvard looked like in 1828. (I did my undergraduate work at Swarthmore, which wouldn’t get going for another 28 years.)

In 1837, a very junior Ralph Waldo Emerson have a speech at the start of the school year. At that time, the US had been independent for about sixty years, roughly the interval that separates us from 1948. The annual celebration of studies, he wrote, was “a friendly sign of the survival of the love of letters amongst a people too busy to give to letters any more.”

Meek young men grow up in libraries, believing it their duty to accept the views, which Cicero, which Locke, which Bacon, have given, forgetful that Cicero, Locke, and Bacon were only young men in libraries, when they wrote these books.

This seems quiet, but it’s quietly hot stuff, a call to revolution. It was hot stuff then: that’s why the US today is filled with Unitarian Universalist churches. And it’s still pretty hot:

“We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds. The study of letters shall be no longer a name for pity, for doubt, and for sensual indulgence.

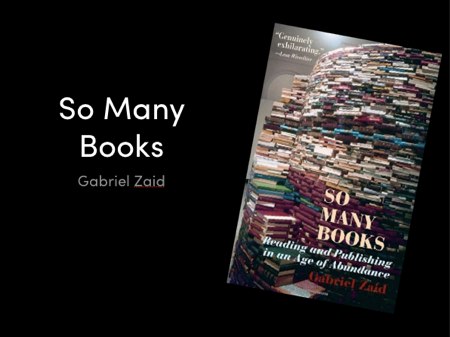

Pity and doubt have certainly returned to the humanities, and it seems they’re seldom farther away from the heart of Digital Humanities than the shadow cast by a rejected application.

This call for self-reliance echoes the best of humanities and, at the same time, indicts the common frailties of #elit. Too often, elit has reacher for tools off the shelf and chosen to say what wass easily said with those tools. Too often, elit has been so worried that those young folks in libraries might find it inconvenient to read the work that elit has lost confidence in making the work at all.