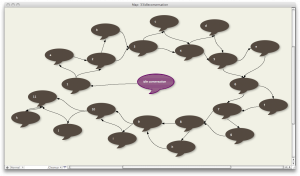

Although I think I agree with the conclusion of Clay Shirky's new talk about Gin, Television, and Social Surplus, the way he gets there is probably not the best route.

Shirky wants to argue that we now have a lot of spare thinking time, time we used to spend watching television sitcoms. By taking a little of our television time and using it to create media (LOLcats, weblogs, wikipedia, whatever), we collectively wind up building amazing new things through lots of small contributions. This is right, but not new: it's Mamet's quote:

The purpose of art is to delight us; certain men and women (no smarter than you or I) whose art can delight us have been given dispensation from going out and fetching water and carrying wood. It's no more elaborate than that.

That might be right, but Shirky argues through historical analogy with the industrial revolution.

The transformation from rural to urban life was so sudden, and so wrenching, that the only thing society could do to manage was to drink itself into a stupor for a generation. The stories from that era are amazing-- there were gin pushcarts working their way through the streets of London.

This sounds good, but inconveniently, it's wrong.

Elna Borch,Death and the Maiden,Ny Carlsberg Glypotek

Yes, early industrial Britain drank a lot. In Nelson's navy, the minimum liquor ration was something like 4oz of rum a day, often supplemented by plenty of beer. This wasn't hard partying, it wasn't decadence; anything less was thought to be cruel and inhuman, even for men to whom weevily bread and the lash were part of daily life. But their great grandparents drank even more; in Medieval Northern Europe, beer was the main staple food for many months of the year.

Wassail! Wassail! All over the town

Our toast it is white and our ale it is brown

Sure, there were gin pushcarts. There were pushcarts for cherries and mackerel and matches and milk, for knife grinding and chair mending. Shops were for rich folk; small businessmen went from door to door. This wasn't new: Gibbons set The Cryes of London for five voices and viols before 1625, and he wasn't alone. This was true almost to living memory; Eliza Doolittle sells flowers on the steps of Covent Garden and her ambition is to someday, somehow, be employed in a flower shop.

Shirky opines that

If I had to pick the critical technology for the 20th century, the bit of social lubricant without which the wheels would've come off the whole enterprise, I'd say it was the sitcom.

This sounds OK, but it can't be right. His canonical examples are I Love Lucy (1951-7) and Gilligan's Island (1964-7); Malcolm In The Middle is mentioned but begins in 2000, a decade after the end of history. There were some who thought the twentieth century included events somewhat earlier. By the time Gilligan starts, the last moment at which we generally think the wheels really came close to falling off was two years past. This is (obscenely) to forget the six million voices crying in the road that the wheels did fall off, and the unnumbered voices ground under those wheels:

As we come marching, marching, unnumbered women dead

Go crying through our singing their ancient cry for bread.

Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew.

Yes, it is bread we fight for -- but we fight for roses, too!

Yes: creativity and appropriation, interaction and re-creation: all are important.

Yes: history shapes this, and yes: this will shape history.

But you've got to get the argument right; sounding good isn't good enough.

Mike Power thinks I'm mistaken. Yes, the gin craze was real, and it was urban. But in the very long view, it's a shift in alcohol. Shakespeare's age drank a lot of fortified wine: sack and malmsey and possets — and a lot of ale. Before then, the middle ages drank even more ale; there was no better way to preserve grain from rodents than to brew it, so much of Europe could either be tipsy or starve. 2.2 gallons per person per year, the 1743 peak, is not that much, even by modern post-temperance standards. Russia's vodka consumption is higher than this, and France's 54 lit=14 gallons of wine per person is certainly in the ballpark. Gin was manufactured and concentrated, which made it ideal in the new industrial cities; where transporting liquids was incredibly expensive, requiring horses and carts and cooperage, concentrated gin made a lot of sense.

In 1896, William Jennings Bryan led the first Populist crusade, a campaign of farmers and workers against Wall Street, the gold standard and the Establishment. He lost, but the memory of that crusade fueled the Progressive Era, much as the memory of working for McCarthy or for Bobby, or walking with Martin, colors our own. Vachel Lindsay remembered the joy of that crusade in the middle of a long poem, written long after the returns came in:

In 1896, William Jennings Bryan led the first Populist crusade, a campaign of farmers and workers against Wall Street, the gold standard and the Establishment. He lost, but the memory of that crusade fueled the Progressive Era, much as the memory of working for McCarthy or for Bobby, or walking with Martin, colors our own. Vachel Lindsay remembered the joy of that crusade in the middle of a long poem, written long after the returns came in: